BOULDER, Colo. — The Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics (LASP) at CU Boulder is the only academic institution to send a spacecraft to every planet in the solar system, but this next mission will be a little closer to home.

They have been selected by NASA to design and build an instrument to investigate the ionosphere, the outer most layer of Earth's atmosphere which gradually blends into space.

“With this mission, we will actually be able to better describe the turbulent nature of this region,” said heliophysics researcher Laila Andersson. "This is really the part of space that can affect society."

Andersson said the ionosphere is constantly expanding and extracting and it's where space weather happens. It's the place where the energy unleashed by the sun comes in contact with energy from the Earth.

That cosmic collision can sometimes create a beautiful aurora, but it can also be hazardous to astronauts, damaging to power grids, and disruptive to communications.

She said our understanding of how the sun’s energy mixes with the Earth's energy is just beginning.

“Because we haven’t flown enough, or measured enough over that region to really understand what’s going on,” she said. "It's a kind of an uncharted part of our atmosphere, previous missions could only last a few months at a time."

The reason this layer of the atmosphere is relatively unexplored is because it’s difficult and expensive to keep a spacecraft in orbit.

Andersson said any spacecraft in this region would require engines to keep the drag from pulling it back to Earth.

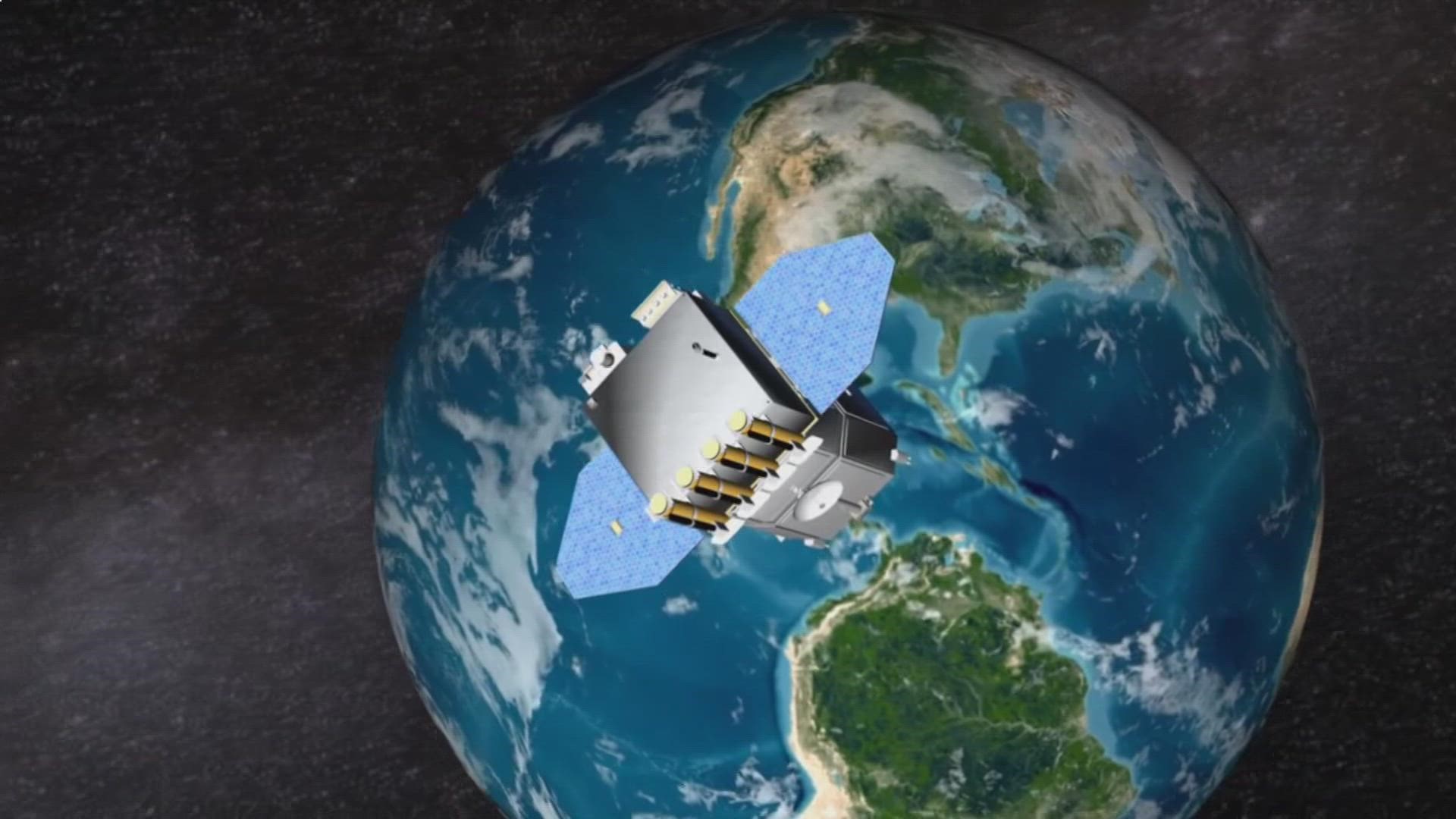

But now NASA will be funding a new group of satellites with the ability to stay in that orbit for three years. It's called the Geospace Dynamics Constellation (GDC).

Anderson and her team from LASP will design and build an instrument called the Atmospheric Electrodynamics probe for THERmal plasma (AETHER) that will ride on GDC to measure the volatility between Earth and the sun.

She said it will gather new data about the density and temperature of the region while measuring how the collision-driven gases and the electromagnetic particles interact with each other.

This data will also fill the gaps in previous observations of the ionosphere.

“There will be a lot of new things that we will find out, that we haven’t thought about,” said Andersson. "It will also help us improve our predictions and understanding of space weather."

She said the GDC satellites will be launching in a few years just as the sun is coming out of a highly active period called Solar Maximum. She expects that we will then observe the most comprehensive measurement of a solar storm impacting the Earth’s magnetic field.

"That is not the main objective of this mission, but for our scientists it will be like Christmas," she said.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Colorado Climate