COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. —

Over fruit snacks and pizza, a classroom of high school students at Rampart High School started learning how to fight white supremacy. Not with might, but with kindness.

Dan Cohen, the assistant education director of the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), said it starts with learning how to push back against bullying and discrimination.

“We want to start with kids in elementary, middle and high schools to start examining the biases and hate around them and be able to challenges those biases and hate,” Cohen said.

Recent figures from the Colorado Bureau of Investigation showed this type of early intervention is necessary. Hate crime reports across the state have jumped from 96 in 2017 to 139 in 2018.

Isabella Polombo, a junior, said she experienced bullying before high school and wanted to do her part to stop others from going through the same thing. Much of the bullying she has noticed at Rampart High School is directed towards the LGTBQ+ community.

“It’s like some people at this school will not acknowledge their existence,” Polombo said. “It’s really frustrating. They’re people. They shouldn’t be treated like that. It’s not ok. And so, I think it’s really important that we’re trying to discuss this because it needs to stop.”

Polombo said they learned how bigotry is formed during the all-day training.

“When differences come to life, I think people get scared,” she said. “That’s really what causes all of these biases and oppression just in general in society today.”

Sixty-one schools participate and host trainings in Colorado and surrounding states as a “No Place for Hate." Cohen said stopping hate before it takes root can prevent it from blossoming into violence.

“We believe if one of the levels goes unchecked and isn’t challenged, then there’s a good chance it normalizes it and it’s easier to go to that next level,” Cohen said. “[Students] see a lot of that base stuff, the name-calling [as] ‘I’m only joking,’ the stereotypes. Things like that. We want them to recognize those and examine those. And be able to challenge those so it doesn’t get to the higher parts of the pyramid.”

After the ADL instructors leave, students are tasked with ongoing education and working with peers to pass along the lessons they learned. Michelle Saab is a facilitator for the ADL’s education department was one of the instructors at Rampart High School. She wanted students to know they are the solution to their school’s issues.

“Our schools are microcosms are what’s happening in the larger world,” Saab said.

Benevolence from the onset could diverge young Coloradoans from a life of hate, Saab said. She added education is the key to changing prejudices and biases which prevents discrimination.

“It’s a lot more difficult to hate and be hurtful and to discriminate against groups and in the world if you are educated on the impact and the systems of oppression,” Saab said. “And when you know, you choose differently.”

Kindness and inclusion are things a former white supremacist said could have made a difference and stopped him from joining.

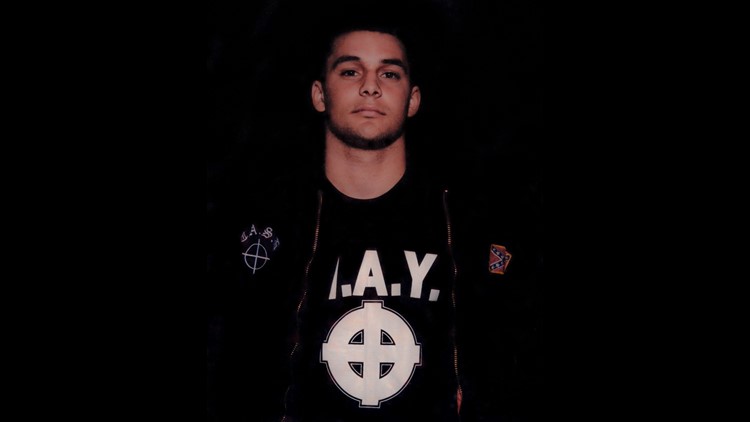

Christian Picciolini, author of Breaking Hate: Confronting the New Culture of Extremism, said he was raised in a loving home that wasn’t racist. But, growing up without much parental guidance made him vulnerable to recruitment.

“Finding the movement was like finding a family,” Picciolini said. “I did feel that sense of identity, community and certainly community through the narrative that was defined for me from a very powerless 13-and-a-half-year-old to someone at 14 who then had this perception of power.”

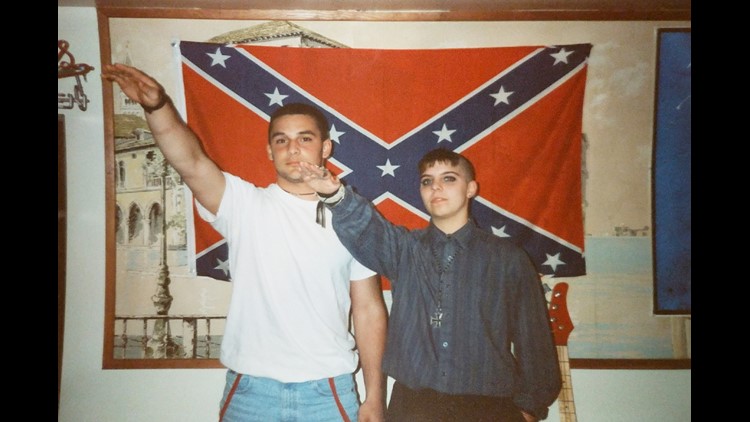

Christian Picciolini as a skinhead

Eight years after Christian Picciolini shaved his head and joined a neo-Nazi skinhead group in Chicago, an act of goodness began to change his mindset on life. An African American customer began going to the record store Picciolini worked in. The customer began striking up conversations with him and the two eventually bonded over their mothers’ breast cancer conditions.

“I was really surprised the conversation we had struck up had been friendly, and the values that were important to us, they matched up,” he said.

Picciolini’s mindset changed as he met more people outside of his social circle that he was supposed to hate throughout his eight years in the skinhead group. People that he may have hurt treated him with empathy and compassion. Picciolini said that willingness to see past the words he said “saved his life.”

“I think I’m very grateful that people were able to see past the monster suit that I was wearing to the broken child that was really wearing it...I felt at that point I had done so much wrong that there was never really any chance for redemption for me, but people never gave up on me,” Picciolini said.

Dr. Rachel Nielsen is the director of the Colorado Resilience Collaborative at the University of Denver. Parents go to her when they are worried their kids may become radicalized if they aren’t deprogrammed.

Nielsen said her organization aims to fill the void as a place where concerned parents can go to for help. They can notice problems, but may not want to go to law enforcement for fear of getting their kids in trouble.

Nielsen said warning signs include a child’s tendency to point the finger at an ethnic group as the cause of problems.

“I would look for things like blaming others,” she said. “More significant language. [Some] racist language. Homophobic language or strongly worded. Anything that’s shifting in a more desensitized or dehumanized direction where a person is now more of a thing or an object.”

Picciolini said indications can look similar to someone who is depressed, alienated, or beginning to use drugs. It usually starts with some “sense of marginalization” and unmaintained “form of trauma.”

“There’s typically those really similar warning signs of changing habits abruptly, of abandoning hobbies and things that they loved for something else,” Picciolini said.

Language can change and the person in question may show more anger, she said.

“[There’s] all the warning signs that we might look for in our children for any type of problematic behavior might be the same types of things that I would say we should be looking for in terms of radicalization or acceptance of an extremist ideology,” Picciolini said.

Nielsen works with patients headed down the path of hate that Picciolini walked before the hateful process is complete.

“To counter the movement towards hate, you have to have people talking about the flip-side,” Nielsen said. “How do you build resilience? How build do you build collaborative efforts? How do you speak to the issue and bring it out of the dark?”

The key is to get to people before they get too entrenched in their hateful ideology, she said.

“If we can get people help in that moment then these things can be prevented,” Nielsen said. “But, when someone doesn’t get help, there’s no compassion for it or solution, people might find that violence is the only answer to get their point across and to show how they’ve been hurt.”

A way to gauge how much interest there is in white supremacy is through what people search for. Moonshot CVE is a partner with the work Nielsen is doing at the Colorado Resilience Collaborative.

“Our search data is collected by combining a series of metrics from search engines providers which enable us to derive an estimated number of searches over time, as well as an aggregated gender and age breakdown of the audience we've identified as being at risk of engaging with violent extremism online,” Ludovica Di Giorgi, manager at Moonshot CVE, said in an email.

Top search terms include white supremacist phrases like “sieg heil,” “1488,” “14 words” and “Heil Hitler.”

Picciololini said using extremist search terms does not mean they are “too far gone,” but are at the next level.

“I would equate you know if someone is searching for certain terms that white supremacists use online, I would equate that to somebody dabbling in drugs rather than somebody who’s just thinking about it, so that would really concern me... That would mean that somebody is at least jogging down the path to extremism,” she said.

Picciolini works to help others get out of hateful extremist movements because he wishes there was someone there for him when he was 14. He said he has helped more than 300 people disengage and is currently working on 400 more.

“What I’m really trying to do is help people come to the conclusion that they were wrong themselves, that putting them in situations that build their resilience so they have more self-esteem, so they don’t have the need to blame other people for the shortcomings they have in their life, that typically are caused by that person and the people around them.”

He said the key to getting out is having a support system people can fall back on after leaving an extremist movement.

“Ultimately what it comes down to is the network around that person, and if there is a stable way to build resilience in that person, to get them to the point where they can actually see a clear perspective what they’re involved with and how they’re affecting people,” he said.

The network he builds can include mental health therapists, life coaches, tattoo removal and job training.

Picciolini said his experience showed him that without a replacement for the white supremacists it would have been tremendously difficult to leave.

“Had I not been accepted by the outside world and given that second chance, it would have been very difficult to disengaged from the movement, because although it was toxic it did provide a sense of community, identity and purpose,” Picciolini said.

If you or someone you know may have concerns about potentially engaging in hateful ideology, reach out to the Colorado Resilience Collaborative online or on the phone: 303-871-3042.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS | Investigations from 9Wants to Know