DENVER —

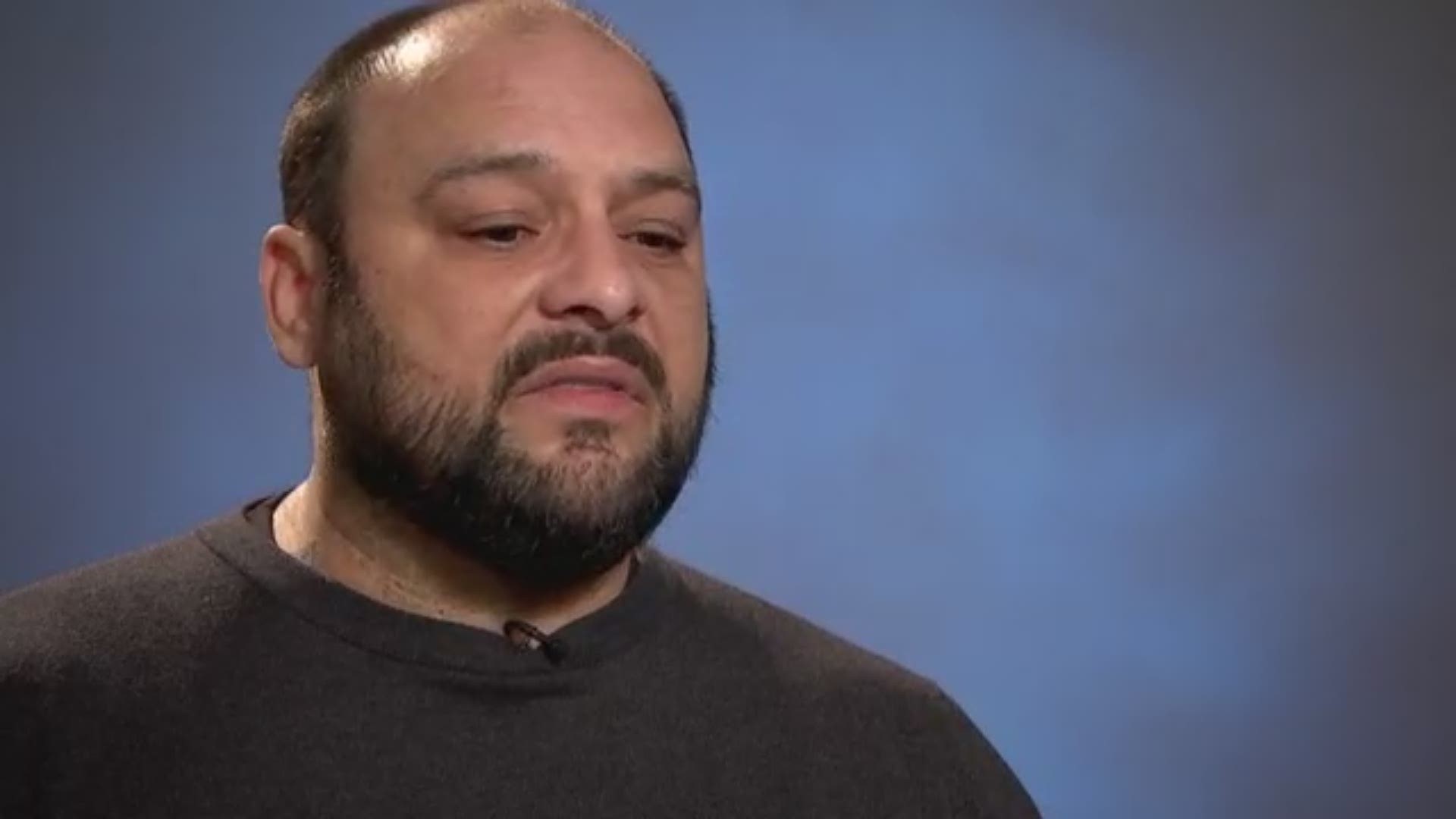

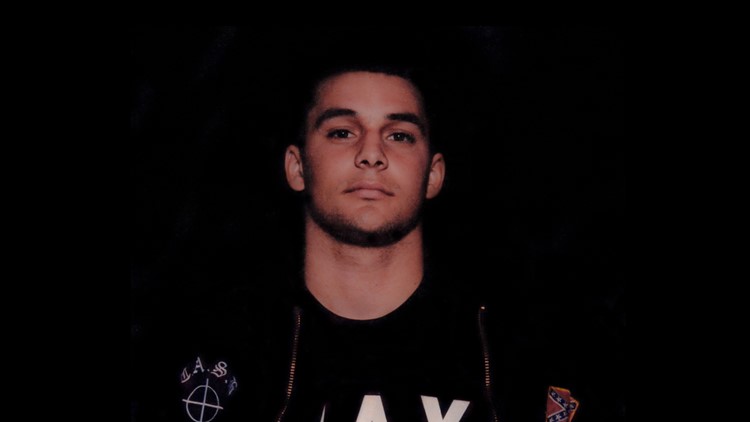

A man who was once a proud member of the white supremacist movement is now devoting his life to help deter others from the same path.

Christian Picciolini, who grew up in Chicago, is an outspoken former skinhead who advocates for listening to people who may be leaning toward extremism and introducing them to the very people they hate. He is also the author of the upcoming book "Breaking Hate: Confronting the new culture of extremism."

9Wants to Know spoke to Picciolini ahead of the two-part series “Homegrown Hate." The second part of the series airs Monday at 10 p.m.

Watch part one at the link below:

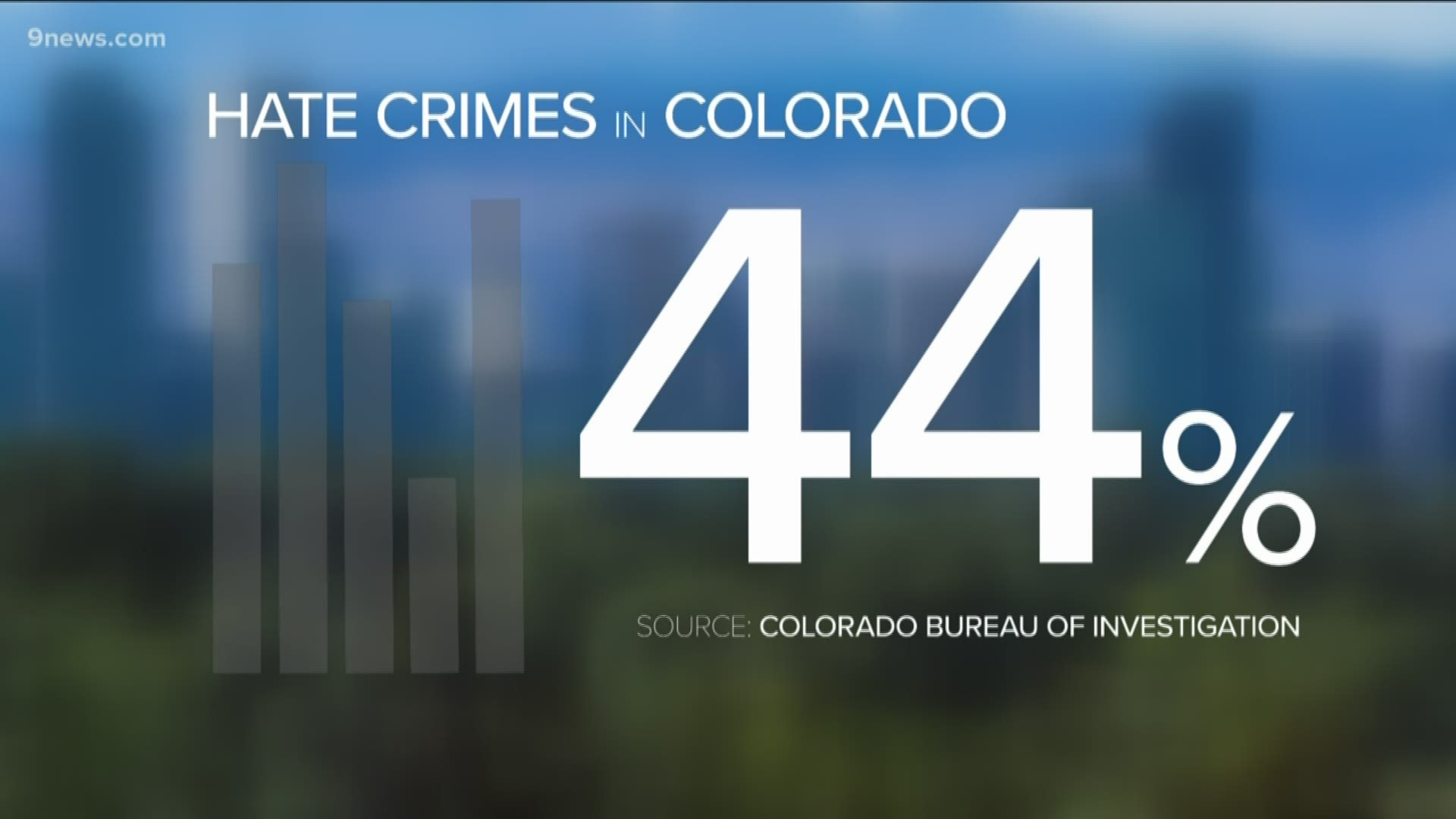

“Homegrown Hate” looks at the rise of extremist groups in Colorado, and questions whether bias-motivated crimes are on the rise.

Read a Q&A with Picciolini below.

Editor’s note: Some of the questions and answers have been edited for clarity and length.

9NEWS: When did you first become involved in a white supremacist group?

PICCIOLINI: “I was recruited into America’s first white supremacist skinhead group in 1987, when I was 14 years old.

“I spent eight years of my life, until I was 23, involved in America’s first white power skinhead group.”

What was the recruitment like?

“I think my recruitment was pretty standard, but what I think most people don’t know is people who are recruited into extremist movements don’t come from broken homes, don’t come from a more stereotypical view of who these people are. I came from a very loving family of Italian immigrants who moved to the U.S. in the 1960s and often struggled with prejudice themselves, were the victims of it. So I wasn’t raised with any sort of racism being the foundation of my family.

“Because my parents are immigrants, they had to work seven days a week, sometimes 16 hours a day. Growing up, I didn’t see my parents very often. I knew they loved me but I often wondered why they weren’t around, so it created a bit of crisis for me growing up, not really having that sort of guidance, so I went looking for a family and it found me in an alley in 1987 on the south side of Chicago.”

You said you joined that skinhead group in part because your parents weren’t around. What gaps did the extremist movement fill?

“I think just like everybody else on Earth, I was searching for a sense of identity, community and purpose. Three things that really drive that decision that we make in life, and at a young age, I had a very difficult time trying to identify what those three things were, how I fit in, who I was.

“Having come from an Italian-American family, I didn’t know if I was Italian, I didn’t know if I was American, and the place where they chose to live was kind of an area where I was an outsider so I didn’t have the opportunity to establish many friendships.

“Finding the movement was like finding a family, it did fill that sense of identity, purpose and certainly community through the narrative that was defined for me from a very powerless 13.5 year old to someone at 14 who then had this perception of power.

“I had been bullied for most of those years growing up, and when I shaved my head and wore boots, suddenly I realized these people who had bullied me would avoid me, so it did fill me with a sense of false empowerment at first.”

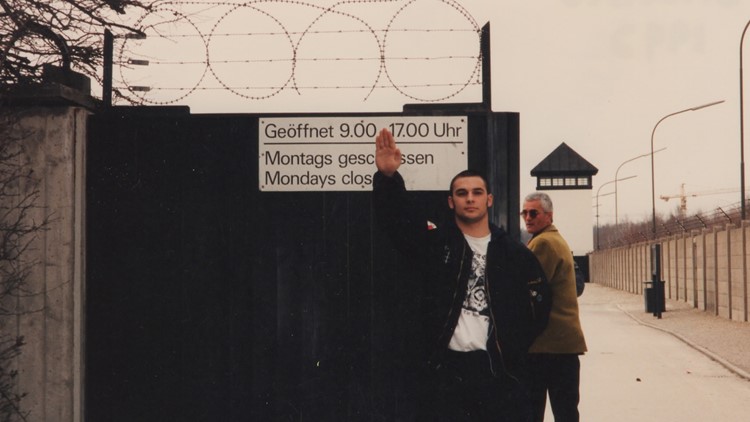

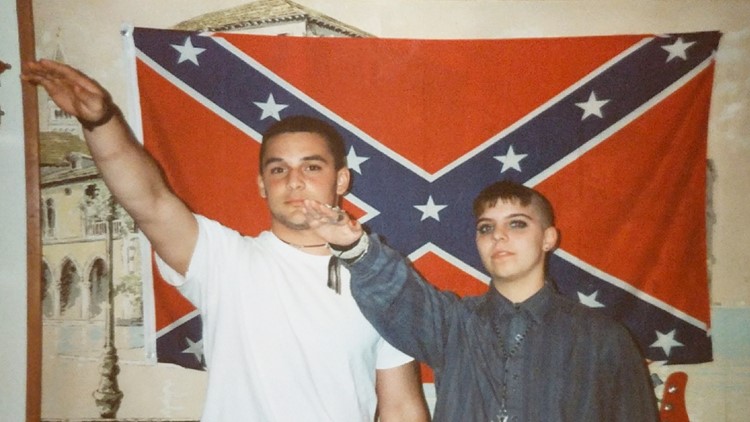

PHOTOS: Photos of former white supremacist Christian Picciolini then and now

What made you want to leave?

“I think throughout the eight years I was involved from when I was 14, it was a snowball effect of events that affected my change and changed my perspective.

“I didn’t have a foundation of racism, so anything I had done to be hateful to other people was almost like a suit of armor to be hateful to myself. It was projected: my own pain onto others. And along the way through those eight years I met people who were outside my social circle, people who were black or Jewish or gay or Asian or Muslim, and those instances where I was able to interact with those people really provided me with a dissonance that built up over time where I was able to replace the demonization that was happening in my head with this newfound humanization.

“I realized I had much more in common with people that I thought I hated than I did with the actual people I had surrounded myself with as a family, and quickly the compassion I received from people I least deserved it from at a time I least deserved it was a very powerful catalyst for me to finally exit and realize that what I had been doing was wrong.”

Was there a particular act of compassion that really sparked a turning point?

“There were several acts of meeting people who I had kept outside of my social network that really impacted me.

“There was one young black man who had come into my record store in 1995, a record store where I was selling white power music. I was still in the movement, but he had come in to shop for some of the other music I was selling, the hip hop and punk rock, and at first I was very standoffish, I wasn’t interested in when he came in, having a conversation with him, but over time he came in one day and he was very upset about something, and I had built up enough of a relationship with him to ask him what was wrong, and he had communicated to me that his mother was diagnosed with breast cancer and he was upset about that, and it was something I could relate to because my own mother had been diagnosed with breast cancer and I was really surprised the conversation we had struck up had been friendly, and the values that were important to us, they matched up.

“In other instances I started to meet people that in other circumstances I might have hurt or might have demeaned verbally, they chose to show me empathy and compassion rather than hate me, and that to me was kind of what I needed … because I always had my defense mechanism up because of what I was doing and the way I was attacking people, and it kind of shocked me when it happened, and it caught me with my guard down.

“What it did was it really planted these seeds inside of me that kind of grew into this understanding of somebody who was the ‘other.’ And I met a lot of people who took that chance on me and I’m really grateful for that.”

What did you find was the key to leaving the group?

“I think the key to finally finding the courage to leave was that I had an opportunity to be accepted into another sense of community, identity and purpose.

“Had I not been accepted by the outside world and given that second chance, it would have been very difficult to disengage from the movement, because although it was toxic, it did provide a sense of community, identity and purpose. It did feel like a family -- a dysfunctional one -- but still one I was searching for that I couldn’t find at home.

“I think I’m very grateful that people were able to see past the monster suit that I was wearing to the broken child that was really wearing it, because I wanted to belong, I wanted to be accepted, but I felt at that point I had done so much wrong that there was never really any chance for redemption for me, but people never gave up on me. They saved my life essentially at that moment, and when they chose to give me a second chance, to see beyond the words that I was saying or the emblems that I was wearing or the music that I was playing, to understand that there really was an ambitious although broken person hiding beneath that suit of armor of hate that I was wearing, and they allowed me a very safe place to work through that, and I’m very grateful for that.”

Is that what led to your current work?

“I left the movement 23 years ago, and it took me a few years to decide I didn’t want to try and outrun my past, because I really did want to try to do that at first, I was scared. I didn’t know how the world was going to judge me and although I was treating other people with respect, I certainly wasn’t treating myself with respect.

“Once I was able to receive forgiveness and actually found a way to be able to seek it and repair the harm that I caused, I knew it was important and critical … to try and disengage people from the same movement that I had helped build.

“I always wished there was someone for me at 14 years old who would have deviated my path into that movement. Unfortunately, that person for me never came but I really do try to be that person for the hundreds of people I worked with. I helped over 300 people disengage from extremist movements and I’m currently working a caseload of around 400 people.”

What’s the key to helping someone get out of the movement, and when can’t you?

“Really understanding and trying to understand if everyone is redeemable and if everyone can be saved so to speak is a tough question, and I really try to look back at myself 25 years ago and I probably was viewed as someone who couldn’t be helped, so I really do have a hard time with thinking that … we shouldn’t at least try to intervene, we shouldn’t at least try to help people disengage from these movements.

“But ultimately what it comes down to is the network around that person, and if there is a stable way to build resilience in that person, to get them to the point where they can actually see with a clear perspective what they’re involved with and how they’re affecting people.

“Oftentimes what I can have with helping people disengage is finding the right partners locally for them and having that resilience, whether it’s mental health therapists or life coaches or even tattoo removal in certain cases.

“Finding that other replacement community and identity and purpose is often my most difficult job and I’ve got to start that by building a network around every single person I work with in their own community.”

What are some indicators that someone is going down the path toward extremist tendencies?

“I get asked quite a bit about what the warning signs might be someone is going down the path of extremism, and what I say to that is our pre-radicalization journeys start the day we’re born, and the things we encounter along our life journey. I call them potholes, the things that detour us maybe to the fringes while we accept this narrative, while we’re searching for a sense of community, identity and purpose.

Those potholes are things like trauma, it could be emotional or physical or even sexual, things like poverty or joblessness, or also privilege. Privilege could be a pothole that keeps us isolated from reality and my job is really to be a pothole filler and sometimes even a bridge builder to the professional services they might need.

“I’m more of a mentor ... I’m not really trying to brainwash somebody or change their minds even. What I’m really trying to do is help people come to the conclusion that they were wrong themselves, and by putting them in situations that build their resilience so they have more self-esteem, so they don’t have the need to blame other people for the shortcomings they have in their life, that typically are caused by that person and the people around them.

“When I do that it’s really amazing to watch them come to the conclusion that their hate is misdirected, it’s wrong, that it’s typically self-hatred they were projecting on other people. I do challenge them ideologically and when they’re ready, I feel that they’re open to this, I introduce them to people they think that they hate.

“So I’ve had a lot of conversations with Holocaust survivors and somebody who used to be a Holocaust denier, and an Islamophobe and a Muslim family, or even somebody who was a homophobe and I try and pair them with somebody from the LGBTQ community. This is to do the same thing that happened to me, to replace the demonization that happened in their life with humanization because what they find often if not always is that they have the same core values and it’s that connection point that really challenges them to open their eyes and accept a new perspective.”

What are some examples of the things you do to give people resilience and self-confidence?

“For some people who’ve maybe spent most of their lives in an extremist movement, you know some of that resilience building could look like job training. They’ve never had a job in the real world, maybe their job was to sell white supremacist paraphernalia from a website, but they’ve never had an opportunity to build a resume. They’ve also never had real meaningful interactions with the people that they think they hate, so it really is about trying to foster those connections as much as possible.

“But the most important thing is if you are really pulling somebody out of a very strong sense of identity, community and purpose, you have to replace that with something else. Otherwise what I’ve noticed is there’s a tendency to really go back, to recidivism or to go sideways to another extremist behavior, and those extremist behaviors can be anything from drug abuse to suicide to spousal abuse and things like that, so it’s critical to offer some sort of a replacement, and identity is really just understanding who they are at their core and really what drove them, what their motivations are, and who they feel a part of.

“Now they feel very isolationist because they’re part of a white supremacist movement, but once they’ve changed their perspective and they start to view the world with an open mind, there’s a multitude of opportunities in terms of who they become involved with or establish themselves with as an identity.”

Are there indicators someone might be going down a path toward extremism?

“I believe the patterns, the warning signs that might be evident are someone who is depressed or alienated or might be getting into drug use or any other extremist behavior for that matter, crime, it typically starts out with some sense of marginalization and typically there is some form of trauma whether it’s emotional or physical or sexual, whether that has really been unmaintained in their lives.

“So anytime we think about ‘why did that kid get into something bad, get into drugs, join a gang, that kind of thing,’ there’s typically those really similar warning signs of changing habits abruptly, of abandoning hobbies and things that they loved for something else, there’s a pulling back in society, a change in language, there’s anger, all the warning signs that we might look for just in our children for any type of problematic behavior might be the same types of things that I would say we should be looking for in terms of radicalization or acceptance of an extremist ideology.

“But we should remember ideology is just the final component, it’s the permission slip that allows them to be angry, to direct that anger at the other rather than themselves, so we need to do a better job of identifying these potholes that are identifying young people, older people earlier in life to make sure we can prevent these behaviors from manifesting in extremist ways.”

If someone has already started looking into white supremacy, can you mitigate it?

“If someone is searching for certain terms that white supremacists use online, I would equate that to somebody dabbling in drugs rather than somebody who’s just thinking about it, so that would really concern me if somebody’s searching for things like the “Holocaust is a hoax” or black on white crime statistics that extremists have used to put out fake news and inflated statistics to try and create a narrative of this extreme black on white crime … I would be very concerned if it was already at that stage.

“That doesn’t mean that person is too far gone, but by then it’s already been at the next level. They’ve been introduced to those terms enough to be able to search for them, that means they’ve already searched for videos, they’ve already read some propaganda and if they’re already vocalizing those terms, it would be something that would further concern me. That would mean that somebody is at least jogging down the path to extremism.

Again, extremism and pre-radicalization really starts to take root the day we’re born and it’s all those potholes we meet along the way, until we land on that narrative that suddenly provides a solution for why we’re feeling a certain way.”

If you see someone you love searching for this kind of thing, what can you do to stop them before it goes any further?

“I think one of the most important things that we can do is listen, as bystanders, as peers, as parents, as siblings … but not to listen to the ideology, to filter that out and listen to the motivation of why that person may be moving in that direction.

“Positive events don’t make people extremists. Things that make people full of joy don’t lead people to extremism, so there’s always some sort of a malignant cause or a traumatic event that pushes someone to the fringe enough to accept that.

“If we’re bystanders, we really need to connect with people. This isn’t about connecting with white supremacists or extremists, it’s really about as humans we need to learn how to connect with each other, we need to learn to listen … rather than to just speak and I think if we really do that we will identify the needs of people long before they take on extremism as part of their life and I think that if somebody’s already down that path, having somebody to be able to talk to not about the ideology or that movement, but about what might be troubling them or what might have pushed them in that direction is always the best place to start.”

SUGGESTED VIDEOS | Investigations from 9Wants to Know