CENTENNIAL, Colo. — Prosecutors brought their case against Alex Christopher Ewing to a close Tuesday morning, using a detailed walkthrough of genetic evidence to show that his DNA was found inside the home where three members of an Aurora family were murdered in January 1984.

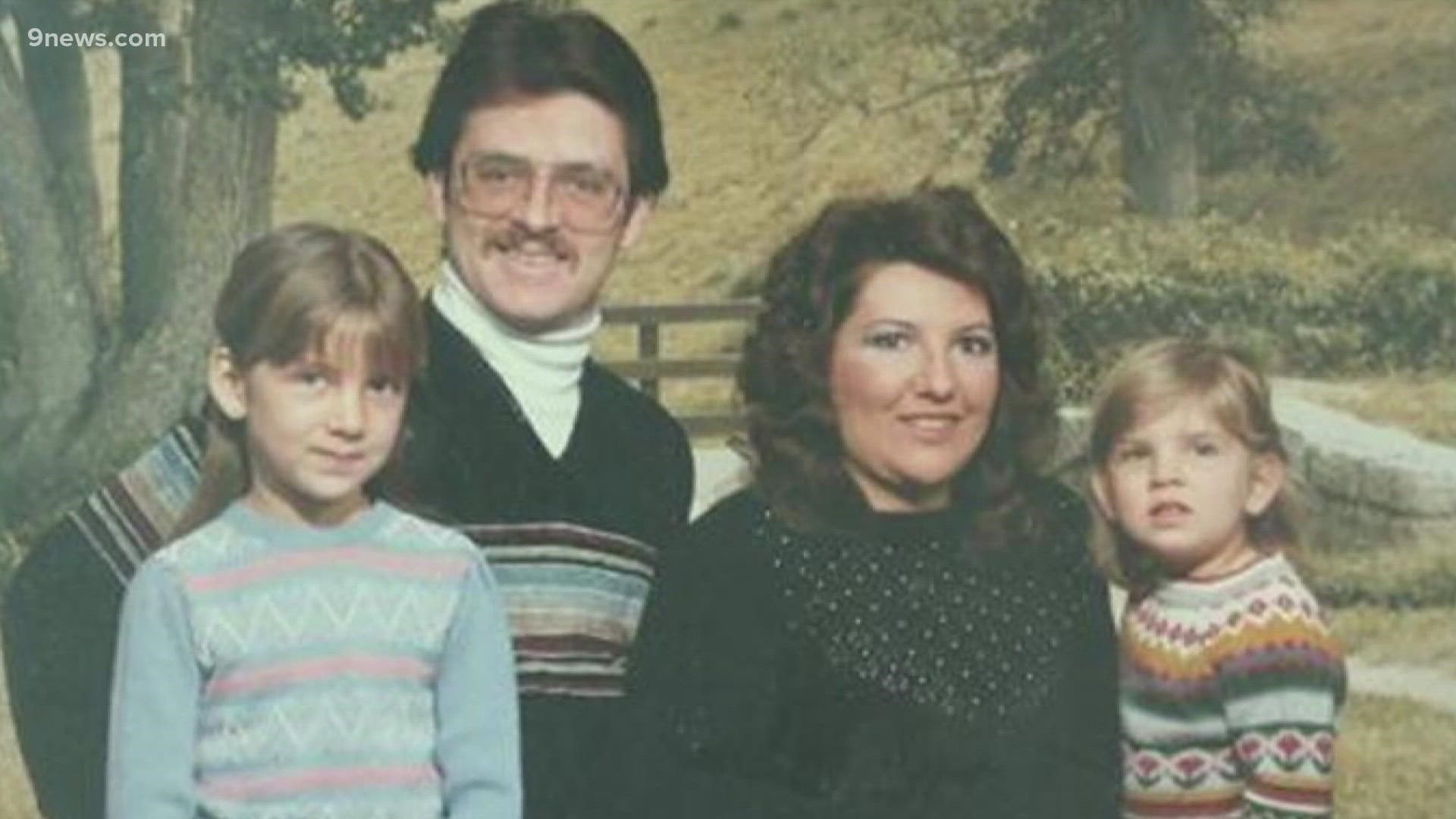

Yvonne “Missy” Woods, a DNA analyst at the Colorado Bureau of Investigation (CBI), was the last of 25 prosecution witnesses called to the stand in Ewing’s trial on multiple counts of first-degree murder in the hammer killings of Bruce and Debra Bennett and their daughter, Melissa.

Melissa, 7, was sexually assaulted in the attack.

After her testimony, which ran more than three hours, prosecutors rested their case – and defense attorneys moved for a mistrial, arguing that recent testing of some evidence left them unable to provide Ewing with effective assistance. District Judge Darren Vahle denied the motion.

Under questioning from District Attorney John Kellner, Woods told the jury that Ewing’s DNA, extracted from sperm, was found on both the carpeting beneath Melissa Bennett’s body and a comforter that partially covered the 7-year-old when a firefighter found her.

Jurors also heard mathematical probabilities that the DNA could be anyone other than Ewing’s.

For example, Woods told the jurors that matching DNA profiles were discovered on the comforter in testing of different sections of it done in 2001 and again in 2018. Both matched Ewing, she testified.

She told the jury the “probability of selecting an unrelated individual at random from the population” with that same DNA profile is 1 in 13 nonillion. That’s 13 with 30 zeroes after it.

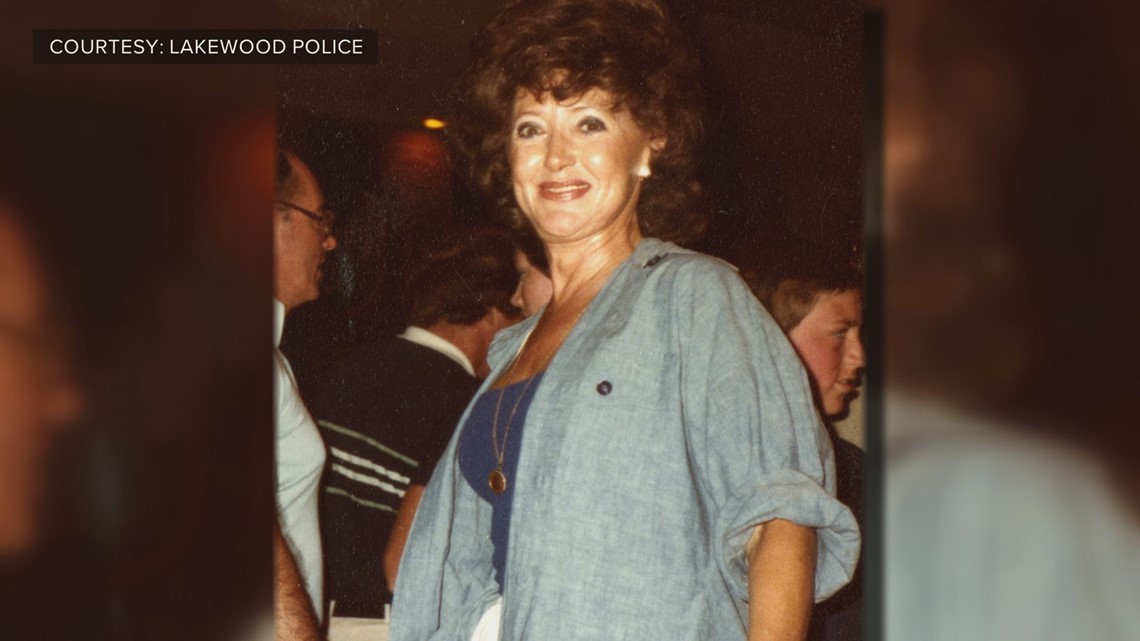

Woods also testified about evidence from the murder of Patricia Smith, a 50-year-old interior decorator who was raped and beaten to death with an auto-body hammer in Lakewood six days before the Bennett murders.

A judge handling the case ruled that the jury could be told about Ewing’s connection to the Smith murder because of similarities to the Bennett killings, although they have not been told that Ewing is scheduled to go on trial in that case in October.

Woods testified that she found Ewing’s DNA on the carpeting under Smith’s body and on a child’s blanket found at the scene.

Defense attorneys Stephen McCrohan and Katherine Spengler have suggested that evidence in the Bennett cases was mishandled – drawing out acknowledgments that some police investigators didn’t wear gloves, that the comforter was dried in a room that was not sterilized, and that the packaging on some items was damaged. They’ve also elicited acknowledgments that some evidence – such as a hair found on Melissa Bennett’s pajamas – was destroyed in testing and that other items are missing.

Some of Kellner’s questions went right to the defense assertions.

For instance, he asked Woods whether, as she prepared to test evidence in the Smith case, any evidence from the Bennett murders was in her lab.

“At this time, no,” she said.

Woods also told the jury that CBI analysts had developed DNA profiles for both Patricia Smith and Melissa Bennett – and as Kellner wrapped up his initial questions he asked about another suggestion of defense attorneys.

“Do you see any evidence of contamination from one case to the other?” Kellner asked.

“No,” Woods replied.

Woods said none of Melissa Bennett’s DNA was found on any evidence in the Smith case – and that, conversely, none of Smith’s DNA was found on any evidence in the Bennett case.

“Is it fair to say that the DNA profile that links those two cases is solely Mr. Ewing’s?” Kellner asked.

“Yes,” Woods replied.

During cross-examination, McCrohan asked Woods questions about a number of items that Ewing’s DNA was not found on – including Smith’s boots, jeans, and panties, which investigators have long believed were pulled off by the killer, and the murder weapon. Similarly, Ewing’s DNA was not found on Melissa Bennett’s pajamas or underwear.

McCrohan also had Woods confirm that there were many pieces of evidence she did not test. That included a knife that investigators believe the killer used to slash Bruce Bennett’s throat, and kitchen drawers the killer appeared to have pulled out.

He also asked her about testing for what’s known as “touch” DNA – genetic material left by sweat or skin cells when a person handles an object.

“Certainly, the only way to know there’s not evidence on any of these items is to test them, right?” McCrohan asked.

“Yes,” Woods said.

She also agreed that DNA from crime scene investigators or investigators could be on some of the items.

“There could be DNA on there from the person who handled these items during the crimes against the Bennetts, correct?” he asked.

“That’s possible,” she said.

But she said CBI does not perform touch DNA testing in crimes that occurred before 2006 “because of the sheer number of people who could have touched it over the years.”

At one point, McCrohan suggested that CBI was “not interested” in testing evidence the killer could have touched and asked if that was a fair characterization.

“No,” Woods replied. “It’s after looking at hundreds of things that were swabbed for touch DNA over the years and realizing it’s not answering the question.”

The question she was referring to is simple: Who committed this crime?

With respect to the knife in the Bennett case, McCrohan pointed out that it wasn’t tested for touch DNA even though that was being done as far back as 2010.

“Swabbing in 2010 is not answering who handled the knife in 1984,” Woods said.

“It would answer whose DNA was on it,” McCrohan replied.

“And all the people who handed it over the years,” Woods said.

Following up, Kellner asked what might have happened if the killer had worn gloves.

“A person wearing gloves could bring any number of DNA profiles to items that they touch,” Woods said.

“And not leave their own?” Kellner asked.

“That’s correct,” Woods said.

He also returned to the effort to answer the investigative question.

“In a brutal sexual assault of a child where there’s semen found at the scene, does it more closely answer the question?” Kellner asked.

“Yes, it does,” Woods said.

“About who committed the rape and murder?” Kellner continued.

“Yes, it does,” Woods said.

After more questions from McCrohan, and some questions from jurors, Woods left the stand a few minutes before noon.

“The people rest,” Kellner said.

Spengler immediately moved for a mistrial, arguing that the defense was handicapped by recent touch DNA testing of evidence in the Smith case. Vahle denied that request – and also denied a defense request to acquit Ewing on all charges after Spengler argued the prosecution had not proved its case.

Defense attorneys have told the judge they need a day or two to present their case.

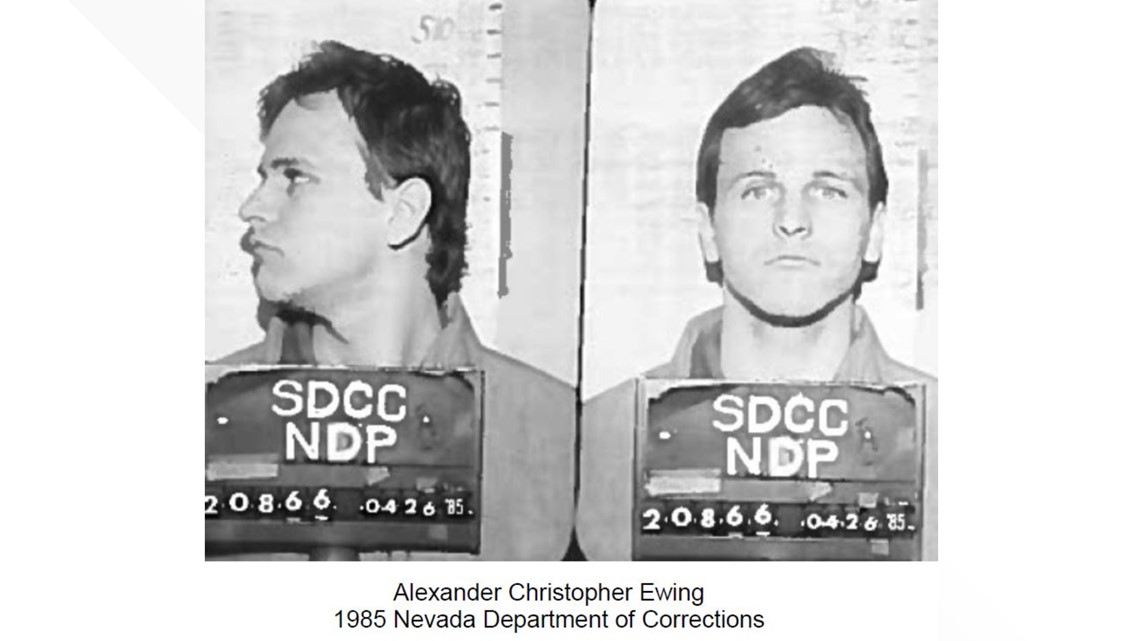

Ewing, 60, was identified as a suspect in the Bennett and Smith cases after a DNA hit in 2018. At that time, he was still serving a 110-year sentence for a late-night ax handle attack on a couple in Henderson that occurred about 7 months after the Bennett murders.

The hit came after Nevada prison officials started obtaining DNA from inmates and adding it to the FBI’s national database, known as CODIS. It was there that it was matched first to the Bennett murders and then to Smith’s killing.

While the jurors have been told that about Ewing’s connection to the Smith’s murder, they can only consider it for “proving identity, for showing modus operandi and common plan, scheme, or design, and to refute any defense of mistake or accident as associated with the DNA evidence.”

Jurors have also been told that Ewing was out of Colorado from Jan. 27, 1984 – 11 days after the Bennett killings – until he was returned to the state to face trial in February 2020.

Contact 9NEWS reporter Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story: kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.

The story of the assaults, the search for a killer, and the anxiety that gripped the survivors and altered life in the Denver metro area is the subject of a 9Wants to Know investigative podcast.

“BLAME: The Fear All These Years” takes listeners back to the attacks and tells the stories of those most deeply impacted — the survivors and the loved ones of the dead. It follows the police investigation through years of cold-case frustration, forensic breakthroughs and the latest developments.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Bennett family murders