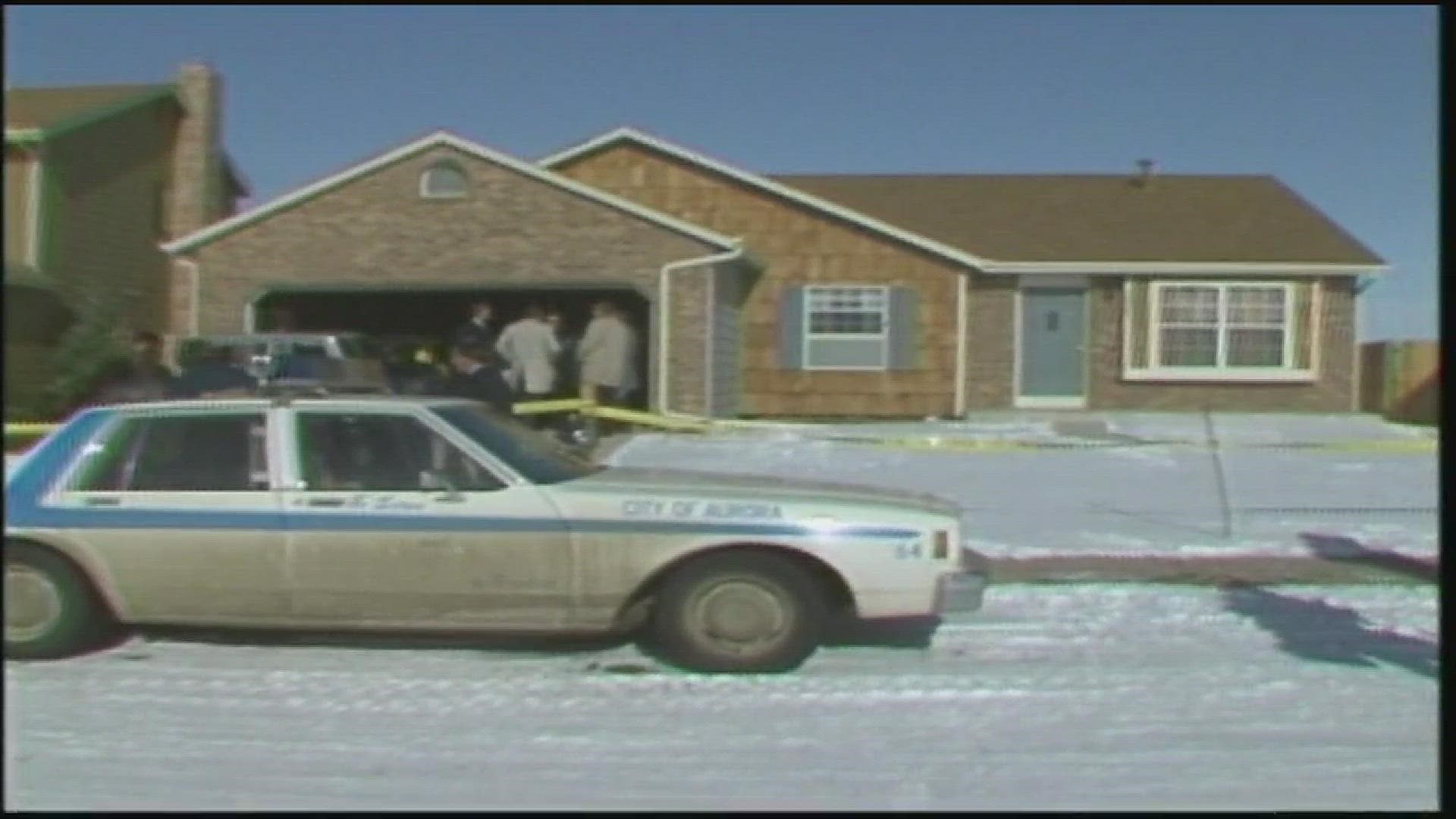

CENTENNIAL, Colo. — For 20 minutes and 24 seconds Wednesday morning, the courtroom was utterly still as jurors watched video footage of the crime scene where a couple and their young daughter were murdered in January 1984.

The video began outside the split-level home where Bruce and Debra Bennett and their daughter, Melissa, died, then moved inside and methodically took the jurors room-by-room through the scene.

>The video above is an original 9NEWS report from 1984.

The only sound was the low hum of the audio system and an occasional cough or sniffle as the video played on a television wheeled into the courtroom and positioned a few steps from the jury box – a step taken because prosecutors asked that the video not be shown on the big screens visible to everyone in the room.

Alex Christopher Ewing, facing multiple counts of first-degree murder in the slayings, sat at the defense table, unable to see the video.

Also unable to see it was Connie Bennett, Bruce Bennett’s mother and the person who discovered the murders. She sat in the front row of the gallery, next to a victim’s advocate.

But jurors watched intently. One leaned forward for a closer view. Some appeared to take notes.

The footage showed the bodies of the victims, some of them close up, who investigators believe were bludgeoned with a claw hammer.

Melissa Bennett was also sexually assaulted, and jurors saw detailed images of her injuries.

The only victim not shown in the video was the couple’s younger daughter, Vanessa, who had already been rushed to the hospital and would ultimately survive serious head injuries and other wounds.

Before the jury had come into the courtroom for the day, defense attorney Stephen McCrohan had objected to playing the portions of the video showing Melissa’s body, saying the jury had already seen photographs of the girl. He argued that the video was repetitive of evidence that had already been admitted and was “overly prejudicial in comparison to the probative value.”

“Certainly, the video will be somewhat disturbing – but of course all of the evidence in this case is disturbing, based on the nature of the crime here,” Judge Darren Vahle said. “Really, this is perhaps the best evidence of the scene as they found it.”

He concluded that the video had “significant probative value” and at the same time was “prejudicial.”

As he considered the objection, Vahle said the prosecution had to prove the nature of the crime, that it was intentional, and that it was committed after deliberation. As a result, he ruled that the value of jurors seeing it was not “substantially outweighed” by the prejudice it might engender toward Ewing.

After the video was played, the rest of the day featured testimony from retired police detectives who had responded to the Bennett family’s home in the 16300 block of East Center Drive on Jan. 16, 1984, the day the bodies were discovered.

And defense attorneys elicited testimony raising question about how key pieces of evidence in the case were handled – specifically, a piece of carpeting from beneath Melissa Bennett’s body and a comforter that was covering her when a firefighter found her.

They are critical pieces of evidence – DNA from both of them was matched to Ewing.

Most of the attention of Ewing’s attorneys was focused on the comforter – and questions about how it was collected and stored.

For example, retired police detective Walter Moeller testified that he bagged up the comforter on the day the bodies were found and transported it to the police department’s evidence locker. But, an evidence tag on the comforter is dated Feb. 14, 1984 – and other paperwork suggests it was booked into evidence on Feb. 17, 1984.

Under cross-examination by McCrohan, Moeller could not explain the discrepancy – and also said that the comforter, which is stained with blood, was likely placed in a room used to dry evidence before it was placed into storage, a step to prevent mold from growing.

But he also acknowledged that multiple pieces of evidence may have been dried in the room at the same time – and that the space was not routinely disinfected.

Left unsaid was the idea that there could have been cross-contamination of evidence.

At the same time, retired Aurora police detective Wilson Egan, the lead investigator on the case for its first two years, acknowledged that a number of fingerprints found in the house were never matched to anyone including Ewing. They included a fingerprint from the front door, one from a Budweiser beer can found in the back of Bruce Bennett’s pickup parked in the garage, and three found on a faucet knob on a vanity between the master bedroom and bathroom.

The prints on the faucet, defense attorneys have suggested, could be the killer’s – a napkin with blood on it was found on the countertop nearby. In opening statements, McCrohan suggested the killer wiped blood off his hands and tried to clean up at the sink, touching the faucet.

Egan agreed that was a possible scenario during cross-examination by defense attorney Katherine Spengler.

He also acknowledged that it seemed important to him when he learned that the water supply to the faucet had been turned off sometime before the killings because of a leak – suggesting that whoever touched it was not a family member.

Prosecutor Megan Brewer, when she got a chance to ask more questions, first asked Egan whether someone wearing gloves would leave fingerprints.

“No,” he said.

Then she asked him about telling Spengler the fact the faucet was turned off seemed important.

“Would semen being found under the buttocks of a rape victim also be important to you?”

“Yes,” he said.

Ewing, 60, was identified as a suspect in the Bennett family killings after a 2018 DNA hit. At the time he was behind bars in Nevada, serving a sentence for a late-night ax handle attack on a couple in Henderson that occurred about seven months after the Bennett murders.

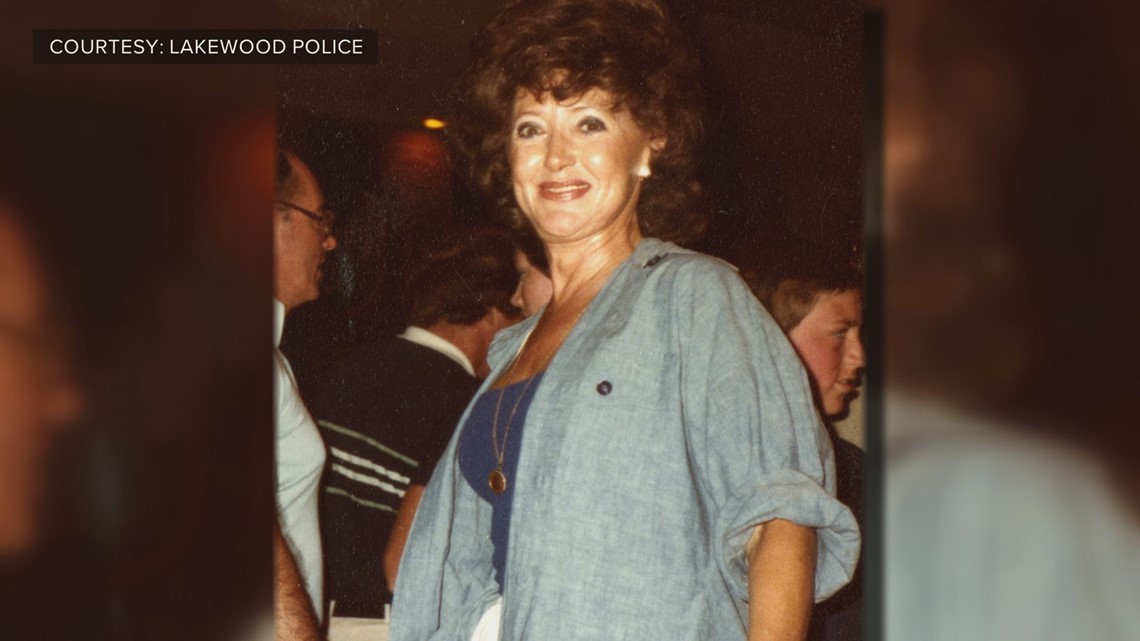

After a 20-month extradition fight, he was returned to Colorado in February 2020 to face charges in this case as well as the killing of Patricia Louise Smith in Lakewood.

Multiple counts of first-degree murder are pending in the killing of the 50-year-old interior decorator, who was raped and beaten to death in the townhome she shared with her daughter and grandchildren. That killing, which occurred six days before the Bennett murders, was carried out with an auto-body hammer.

Ewing is scheduled to go on trial in that case in October in Jefferson County.

The case is the subject of a 9Wants to Know investigative podcast. “BLAME: The Fear All These Years” takes listeners back to the attacks and tells the stories of those most deeply impacted — the survivors and the loved ones of the dead. It follows the police investigation through years of cold-case frustration, forensic breakthroughs and the latest developments.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Bennett family murders