BOULDER, Colo. — Wildfire smoke from New Mexico has been pushing into Colorado for several days now and some of it could come close to the Denver area on Wednesday morning.

One of the best tools in forecasting wildfire smoke is a computer forecast model developed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) in Boulder called the High-Resolution Rapid Refresh Model (HRRR).

It was originally designed as a weather model, and that is still its main function, but its wildfire smoke algorithm has become widely popular over the last few years.

And since it's mainly weather that drives wildfire behavior, the solutions are relatively accurate.

“We rely on the satellite detection to identify the locations of the fires,” said Ravan Ahmadov, a research scientist with the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), the extension of NOAA at CU Boulder.

He said that once the satellite identifies the heat signature of a wildfire, the data is fed into the HRRR which determines the size, location and intensity of the fire.

It then uses data like local weather conditions surrounding the fire area, the terrain of the area, and the type of vegetation being burned, and the model predicts the amount of smoke the wildfire will produce over the next 18 hours.

"Not only do we simulate the complex process of fire plume rise, but our model also simulated how the smoke can travel hundreds of miles away from the source at all different levels of the atmosphere," said Ahmadov.

It's generally a wind forecast that will guide its movement, and dispersal of the smoke once it gets airborne.

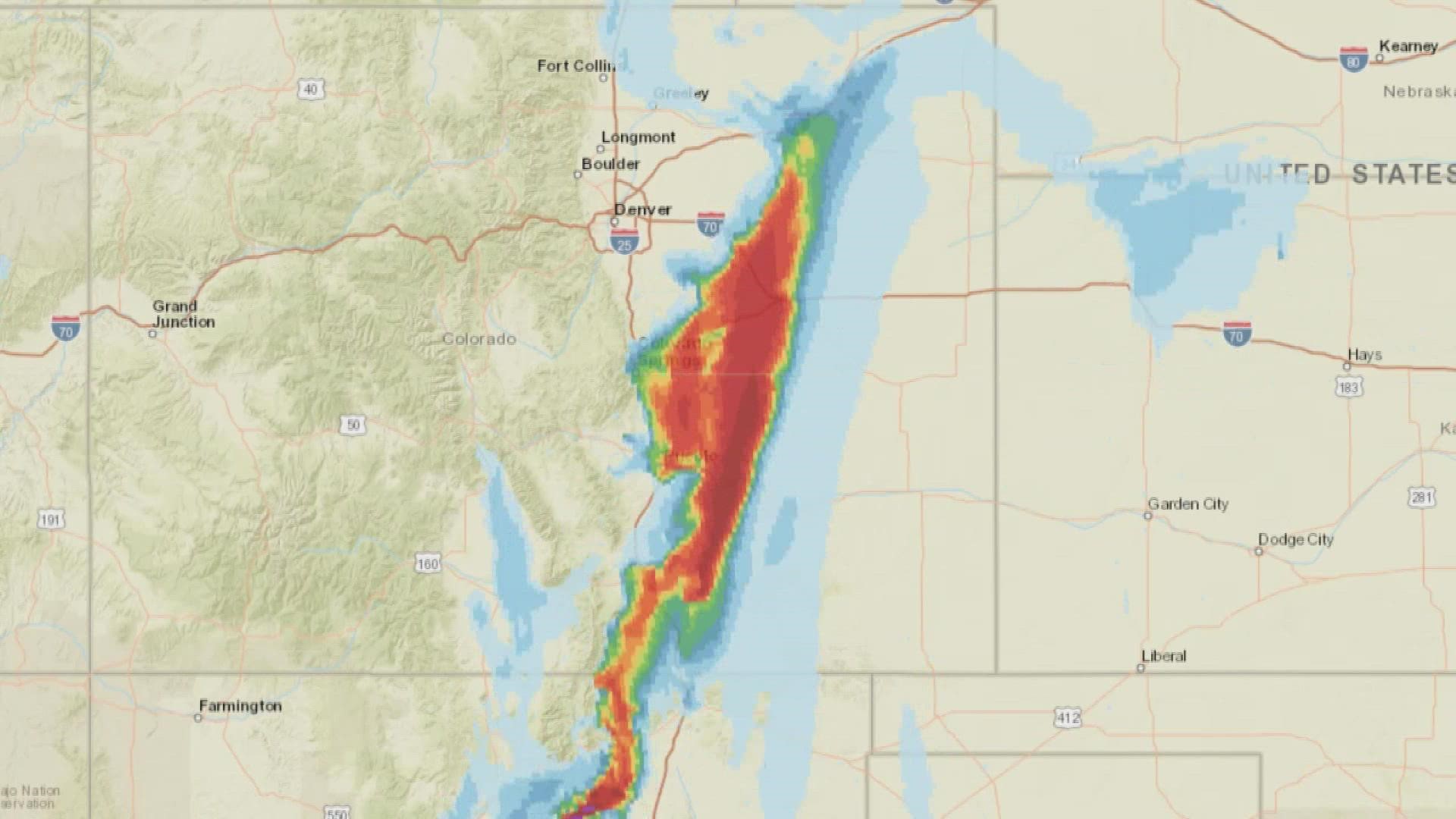

For instance, the HRRR model was forecasting a wind shift late Tuesday night that could push the New Mexico wildfire smoke close to the Denver metro area by early Wednesday morning.

It shows much of the eastern plains having some impact, at least at high altitude over the course of the day Wednesday.

Wildfire behavior can change rapidly, and the HRRR model can keep up with those changes. If the weather conditions unexpectedly change, which the heat of the wildfire itself can do, the model can identify those changes and incorporate that into a new solution that it computes once every hour.

The smoke portion of the HRRR model had been in an experimental phase for several years but just became fully operational in 2021. Ahmadov said that gives it designated and reliable space on the NOAA supercomputer, so there will not be any interruptions to its service.

And it was put to good use by many National Weather Service and commercial meteorologists during a busy western wildfire season last year.

“I think the model did a pretty good job," said Ahmadov. "We have received quite positive feedback from the forecasters.”

A NEXT GENERATION WILDFIRE SMOKE MODEL

NOAA is in the process of reworking the entire framework their computer modeling program into a new system called the Unified Forecast System. Ahmadov said they are taking advantage of that transition to create the upgraded replacement for the HRRR which will be called the Rapid Refresh Forecasting System.

"It will cover all of North and South America at three kilometer resolution," said Ahmadov. "The new model will have improved physics, improved data assimilation capabilities, and it will have a new dust forecast capability."

He said one of the biggest improvements that will come with the new smoke model, will be how it initializes the source of wildfires.

The current HRRR model only uses data coming from polar orbiting satellites that only go around the earth twice a day. So, if a wildfire starts just after the satellite passes by overhead, it could be twelve hours before the satellite gets a fix on it.

There could also be cloud cover at the time the satellite passes over a wildfire. Or the beam of the satellite might only cover part of the wildfire.

For the HRRR to be accurate, it has to get an accurate fix on the size, location, and amount of heat coming from the fire.

The new computer model will be able to use data from some of the geostationary weather satellites like GOES-16 and GOES-17. That way, wildfires will be detected immediately and be in view at all times.

Geostationary satellites do sacrifice some resolution however at 22,000 miles above the earth. The polar orbiting satellites are only about 500 miles up.

The new model may begin testing in Boulder this summer but won’t be operational for at least a couple of years.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Colorado Climate