COLORADO, USA — It would be unlikely — but not impossible — for the Calwood and Lefthand fires to have been caused by a long range ember.

That's according to two fire behavior analysts who 9NEWS interviewed to gain some perspective and science background pertaining to this years strange spot fire activity.

Large wildfire debris have frequently been discovered in backyards along the Front Range this wildfire season. One spot fire even jumped a mountain range.

The Calwood Fire burned more than 10,000 acres in Boulder County, the largest in its history. The Lefthand Canyon burned 460 acres.

Mountain-jumping embers

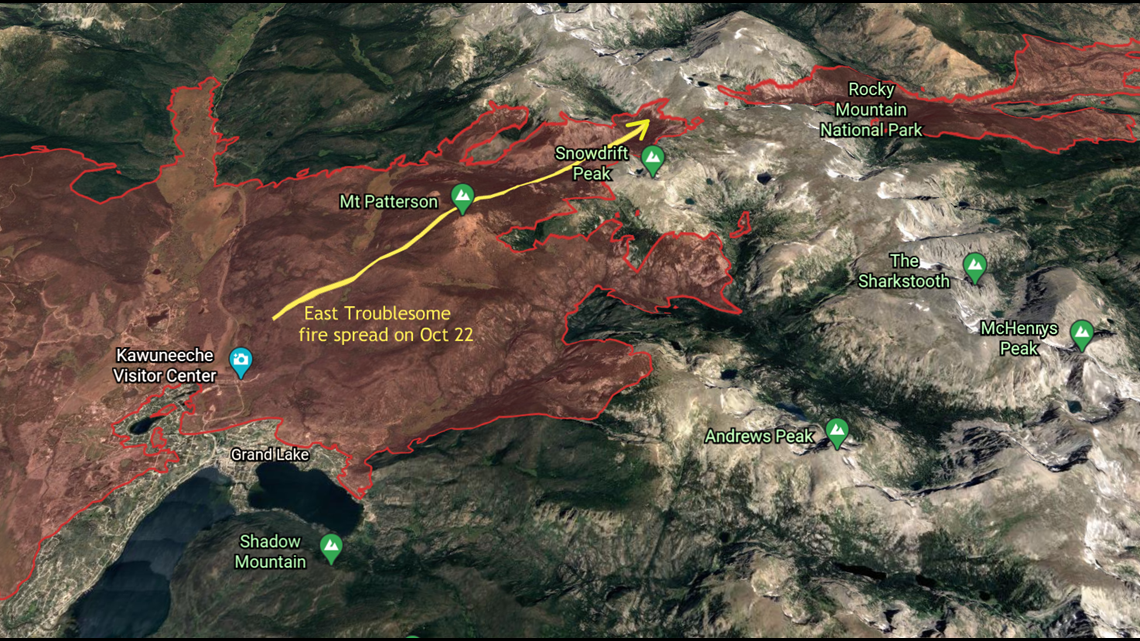

On Oct. 22, the East Troublesome fire near Granby spread rapidly eastward in high winds. It aligned with the Tonahutu Creek drainage basin and used the dry fuels located there to climb up the slope.

Once the fire reached the top of the treeline near Sprague Pass, embers started jumping over the Continental Divide.

"And it's not like there were just one or two stray embers. We’re talking about thousands and thousands of these embers being blown across,” said Rocco Snart, a fire behavior analyst with the Colorado Division of Fire Prevention and Control.

Snart said a few of the embers from East Troublesome managed to fall in some dry fuels located in the Spruce Creek drainage on the other side of the Divide. That started a few spot fires near Mt. Wuh in Rocky Mountain National Park.

He said the sheer number of embers being sprayed by East Troublesome made it likely that a spot fire would happen, but it was also the short distance that helped make it possible. The flight of those embers would have been just about 1 1/2 miles.

“That ember has to be able to stay lit long enough, once it’s in the air, that it has enough heat when it lands,” said Glen Lewis, a fire behavior analyst that was assigned to the Cameron Peak fire at the time.

Lewis said that most spot fires happen less than 1/2 mile away from the parent fire, but it is still common for them to spot up to 2 miles away. Anything beyond 2 miles is very rare.

Not the first time

A wildfire jumping the Continental Divide is a truly rare event, but this was not the first time its happened. It's not even the first time in Colorado. In 2013, the West Fork Complex fire jumped the Divide near Wolf Creek Pass.

"I remember for days they were saying, 'It's not going to cross over, there's no way it's going to cross over,'" said Snart. "And sure enough, it eventually did jump the Divide. That's why I never say never with wildfires."

Long-distance spot fires

Some of the longest spot fires ever documented have been 18-22 miles away. Those happened during the 2009 Black Sunday bushfires in Australia.

There are several factors that need to be present in order to get long distance spotting.

The original fire debris needs to be large for it to stay burning over a long-distance flight.

"That ember will gradually burn over time and distance," said Lewis. "If the entire ember is consumed before it lands, there will not be enough heat left in it to start a new fire."

That large ember also needs to get lifted high into the atmosphere to allow it to be carried a long distance by winds. So there has to be a strong convective column over the fire.

"The heat over a large wildfire can get so intense that it will convectively lift the column of air above it as high as 5 miles into the air," said Lewis. "That means that even large embers are getting lifted somewhere near a mile high."

The ember can't go too high though. The sub-zero temperatures high in the atmosphere will work to cool the ember.

High winds are necessary for two reasons. That is usually how a convective column reaches temperatures high enough to launch large fire debris to the height needed to be transported long distances.

And high winds will also be responsible for the long transport distance.

"That's another spot where the formula gets complicated," said Lewis. "The strong winds that are needed to transport the ember [are] also responsible for putting it out, so there needs to be the right balance of size, height and wind."

And finally, if all those ingredients are present and an ember is capable of staying hot long enough to reach a great distance, it must also land in a spot that is conducive for fire ignition.

The right conditions

Colorado has had the right conditions that would support long distance spot fires.

Large fuels are present in the form of dead standing beetle kill. That would allow a better opportunity for large but lightweight fire debris to be lifted high into the atmosphere.

High wind events have been frequent, both on Oct. 22 when the East Troublesome jumped the Continental Divide, and on Oct. 15-17 when the Calwood and Lefthand fires were born.

And the fuels are at near record dryness. The moisture deficit in Colorado's air during the month of October was also at record low levels. These factors increase the likelihood of any ember being able to ignite a spot fire after a long flight.

Front range fire debris

Residents along the Front Range have been finding large pieces of fire debris in their backyards for months now. Some of those pieces have fallen as far as Greeley, a good 30 miles from the Cameron Peak fire.

We have not received any reports of any of those charred chunks containing any heat though.

Calwood and Lefthand spotfire theory

A long distance spot fire is clearly difficult and unusual, but it is mathematically and physically possible to, on occasion, transport great distances.

So, could the Lefthand and Calwood fires have been caused by long range spotovers from East Troubelsome fire?

Those fires started on Oct. 17, just a day after the East Troublesome fire had explosive growth, with the winds blowing directly to the east towards Boulder County.

The cause of both those fires remains a mystery and under further investigation. Lightning from a thunderstorm can be ruled out, which means human error or downed power lines are the most likely culprit.

For those fires to have been caused by long distance spot overs, embers would have needed to travel about 30 miles.

“So that would have to be a very large ember that would have to be ignited, maintain ignition all the way up over the Divide again, and then fall out down there," said Lewis. "So, it would be really an extraordinary event for something like that to happen.”

Both fire behavior experts agreed.

“That would be a bit of a stretch even in my mind, and I’m pretty capable of thinking outside of the box,” said Snart.

Downhill spotting

"Most people think of spot fires as flying embers, but another type of spot fire is one that gets caused by fire debris rolling downslope," said Snart.

He said pine cones and burning logs rolling downslope and often cause spot fire. This happened at the Ice fire in southern Colorado. Snart said a state multi-mission aircraft witnessed embers rolling downhill and starting spot fires.

He said that can create a dangerous situation if embers can slip past wildland firefighters engaged in a direct attack on the fire line and get trapped by a spot fire forming behind them.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Science is Cool