DENVER — By 4:30 p.m. Thursday, an avalanche warning in Ophir and other parts of the San Juan mountains expired.

On Wednesday an avalanche knocked out power in the town for several hours, and mitigation efforts had been underway in the mountains there.

Since Dec. 26 of last year, avalanches took the lives of four Coloradans, prompting a warning for those venturing out into the backcountry.

“We have seen more avalanches this year than we do on a typical year, and recently they’ve gotten much bigger,” said Ethan Greene, director of the Colorado Avalanche Information Center, in a January release.

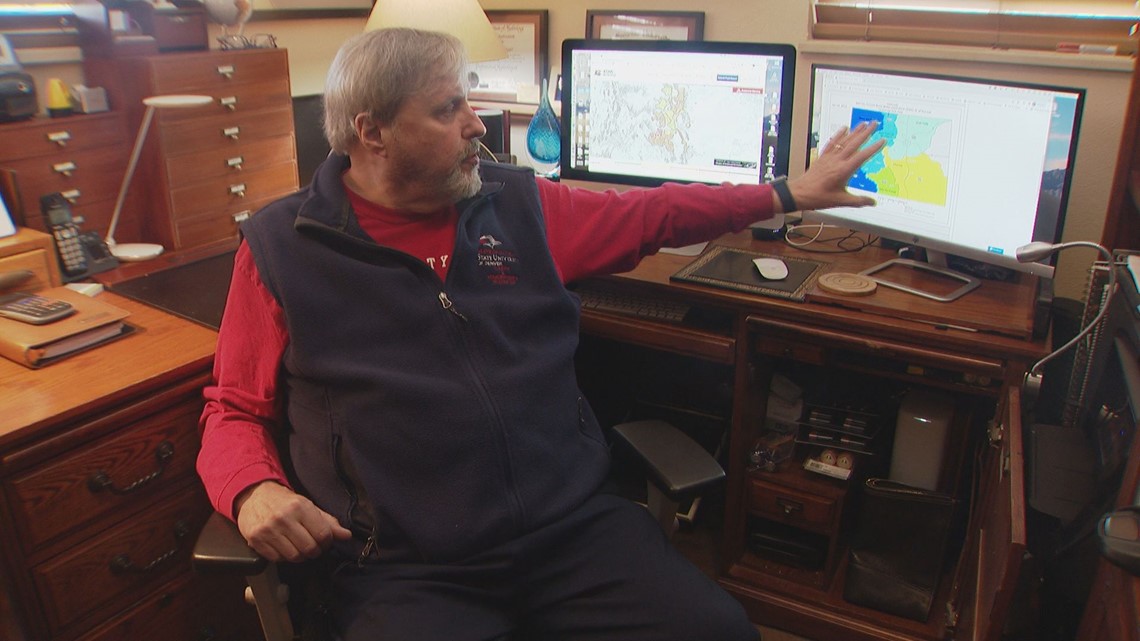

Dr. Tom Bellinger, a longtime hydrologist turned adjunct professor at MSU Denver modeled river basins and forecasts for snow.

His courses included teaching students about how to analyze avalanche danger, even taking them to the mountains in the past to see the dynamics firsthand.

When it comes to this season, the sheer amount of snowfall the mountains have received has played a big role in the recent avalanches, but with a few complexities, he explained.

"And also what happens in between snowstorms to the snowpack to create different layers of strength within that snowpack," he said. "So that could be a settling of a snowpack. It could be melting of the surface of the snowpack creating an ice layer. And it might have various layers. If you dig into a snowpack, you'll see different layers where there might be different storm events. And every time there's a layer, you have the potential for something that could fail."

What also plays a role, he said, is how the layers of the snow may change over time.

"So let's say we have an old snowpack that's been sitting there and maybe it's got a glazed ice surface from wind or rain or something like that, and then you get a heavy snowfall, suddenly that new snow is sitting on top of a weak layer or a slippery layer or just something that can fail. And some type of disturbance, it could be a snowmobile, a skier, it could be just more snow adding to the load, etc. And essentially what happens is that might fail at that weak point where the layers are very different in density and how they're made up and then suddenly the snowpack lets go."

The other side of the coin to this, he said, has to do with climate change that could prompt dry spells or heavier snowstorms. While dry spells usually mean less snow and lower risk, the timing of the dry spell could change things.

"And let's say you've had a bit of a dry spell in, say, February, and things tend to maybe ice up a little bit and the snowpack hasn't been snowed on very much. When you get into March, which is our heaviest snowfall month, suddenly you get a big jump of snow and all that snow is laying on top of those weaker layers that probably have formed through the dry spell," he explained.

Overall, the factors that go into this season are a mixed bag, he said, but on a separate note, he believes the snowfall in the mountains can be a bit of a double-edged sword because of the present danger.

But meanwhile, he said the snow melt can help recover the Colorado River levels, which is another issue recently reported on.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Severe Weather