BOULDER, Colo. — Artificial intelligence (A.I.) is everywhere.

“It’s on your phones, it’s driving your social media page,” said David John Gagne, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

And now it's in weather forecasting.

Gagne is using machine learning to train computers to forecast severe weather.

“We’re interested in looking at ways to give people an alert that hail might happen in the next day or so,” Gagne said.

The AI uses facial recognition systems.

A computer program can be taught to recognize a person's facial features, and then automatically identify that person in other pictures or videos.

Gagne said applying that same technology and using modeling to teach a computer what a hail storm looks like can ultimately lead to something similar, giving a forecaster an alert that hailstorms may be coming soon.

“Part of the idea with this tool is to make it easier to drink from the data fire-hose, because there are so many different models that come out every hour, every day,” Gagne said.

Gagne developed a deep learning model he calls a "convolutional neural network." He trained the machine by showing it images from NCAR’s vast archive of storm data.

"The machine learning algorithm searches image data for shapes and patterns and converts that into some kind of answer, whether that be the identity of a certain person, or whether or not a storm will produce large hail," Gagne said.

Powerful thunderstorms will look very similar because it is a similar wind shear pattern that creates and ventilates the strong updrafts responsible for dropping large damaging hail.

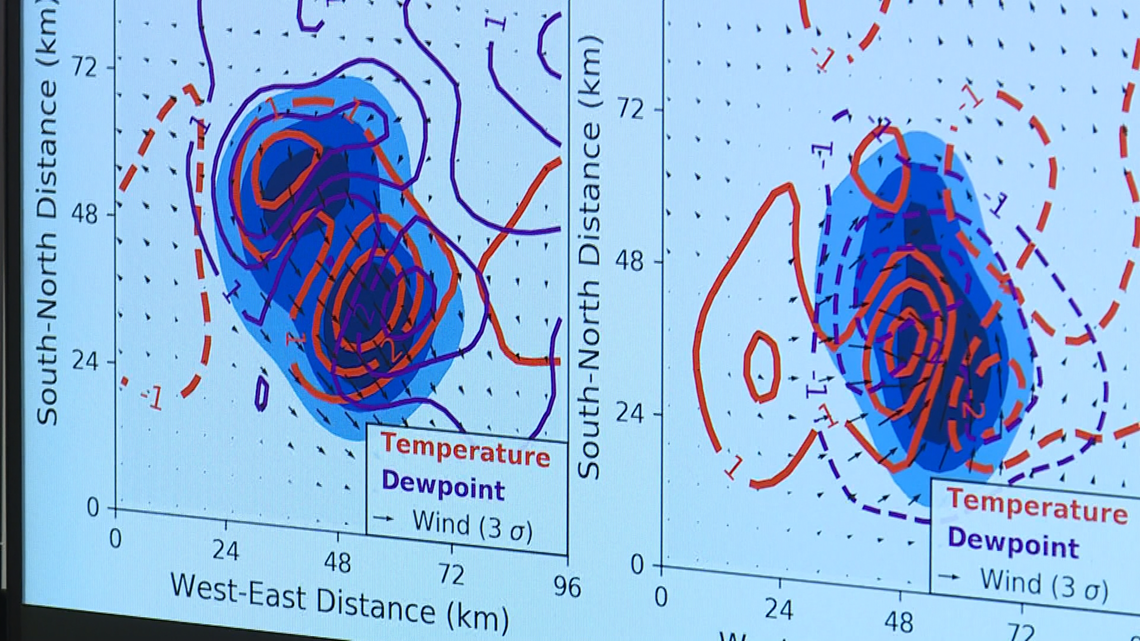

One of the ways Gagne was able to verify that the computer was learning the correct aspects of a hail storm was to essentially run the model backwards, asking it to produce what it thought would be the perfect hailstorm.

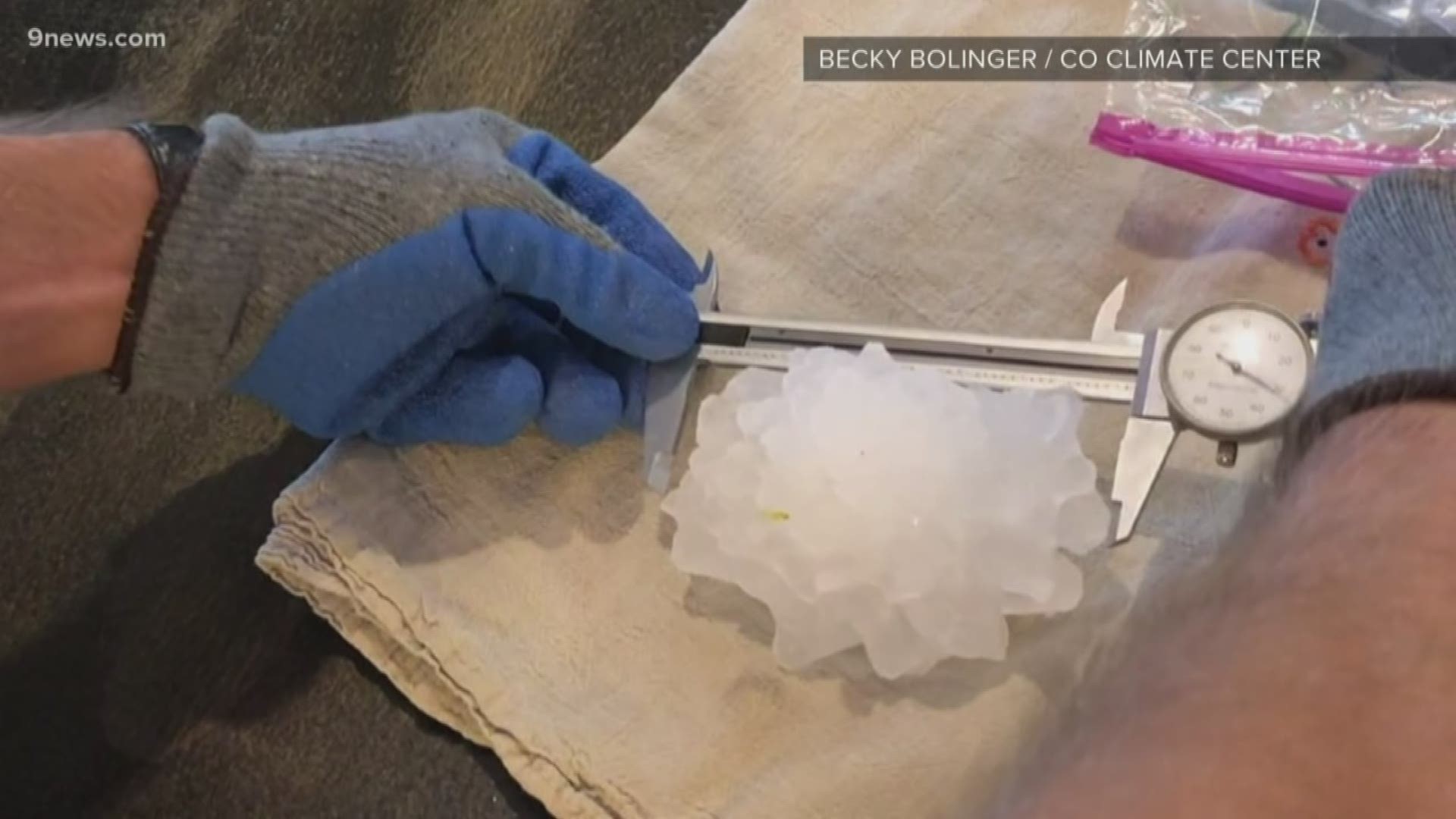

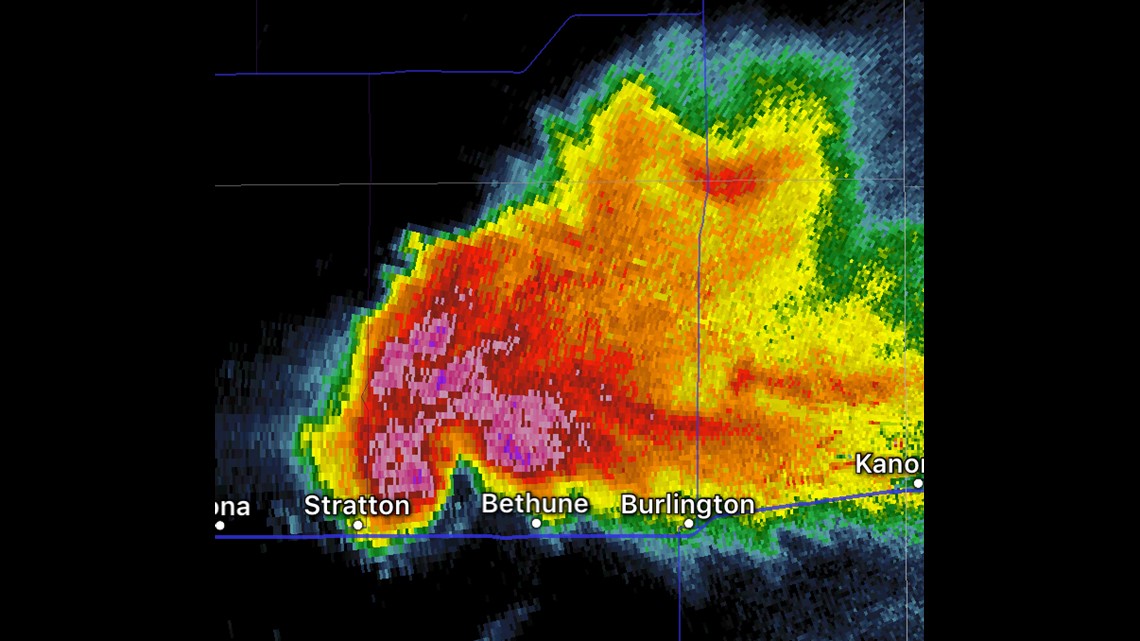

In one case, the machine produced a situation where a small supercell merged with a larger one. Interestingly, that's exactly what happened with the storm that produced Colorado’s new record hailstone in Bethune last Wednesday.

Initially, Gagne said he was getting a lot of skepticism from the meteorology community because the model isn't physically based. It doesn't ingest heaps of weather data and meteorological formulas, but that may actually be an advantage to this system — to balance other weather models with a fresh view.

“I’ve been able to convince a lot of them that this is quite a viable thing," Gagne said. "Now there’s been a huge explosion in meteorologists wanting to do their own machine learning on different problems.”

SUGGESTED VIDEOS | Science is cool