IDAHO SPRINGS, Colo. — On a cold and snowy day in Idaho Springs, an army of scientists descended the slippery banks, hugging Clear Creek and marching through the water.

It was the first snow of the season, and onlookers unlucky enough to be caught out in the storm stared through the flakes at the men and women wading upstream.

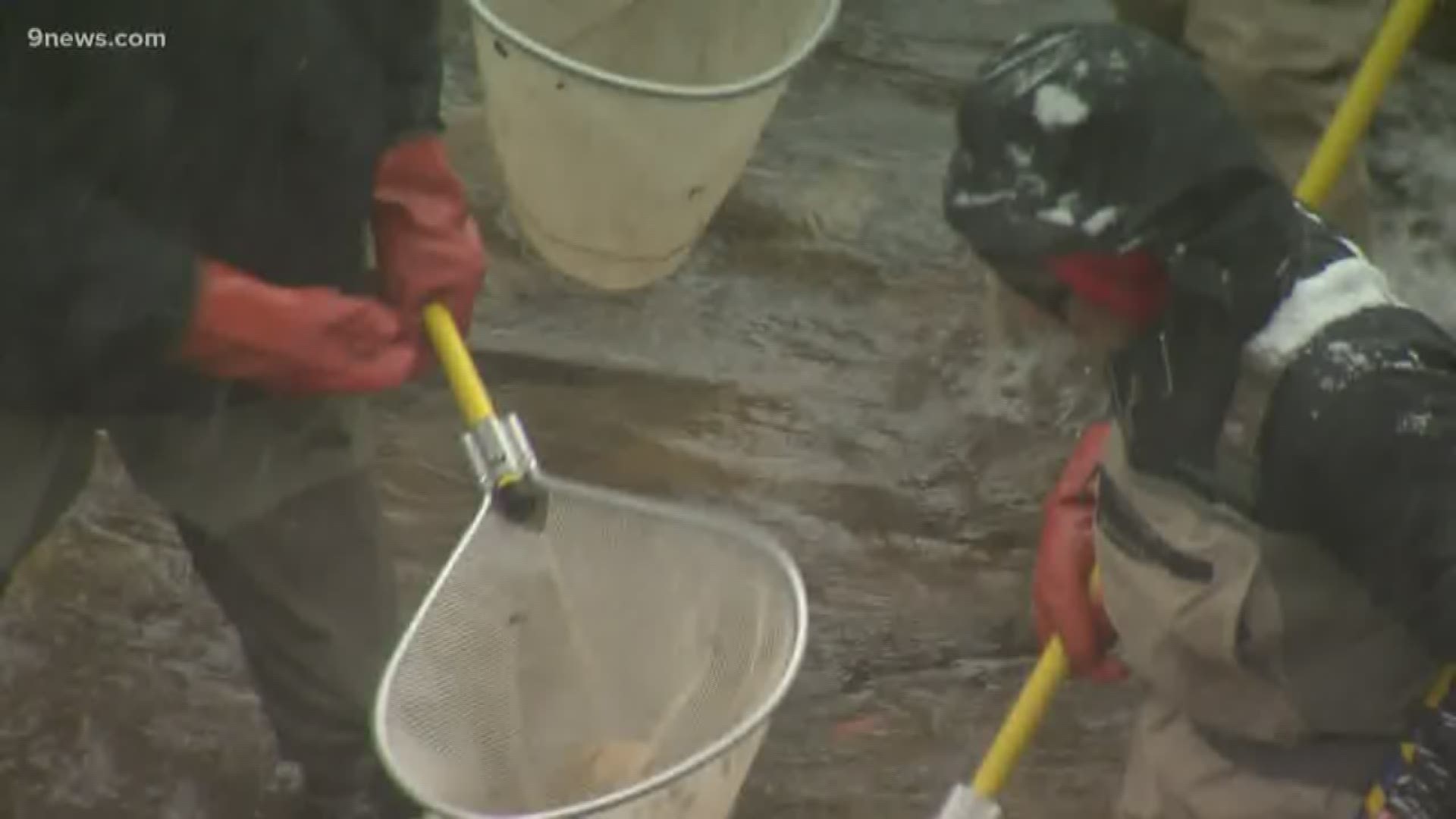

It must've been a strange sight — a slow-moving mass working against the current, some scientists guiding yellow poles through the water, others walking behind with long nets.

The scientists were electrofishing, which involves using poles that send electrodes out that stun the fish, making it easier to net them. The team member's rubber boots and waders kept them safe from the electricity in the water.

"It's one of the most important tools that fish biologists worldwide have at their disposal," said Paul Winkle, the leader of a team of Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) aquatic biologists and technicians.

Winkle's target is trout and his team recently conducted CPW's annual fish population survey for Clear Creek.

"It give us an idea of the health of the ecosystem," Winkle said. "If the fish aren't doing well, there's something going on."

This is the 16th year Winkle has done this survey, scouring four sections of the creek from Georgetown to Golden one year and a different set of four the next.

October is usually the ideal month for the week-long ritual, he said. The flow of the creek is too high and dangerous during the summer snow runoff, fish that hatched in the spring are too small to catch and count until fall, and snow doesn't usually start falling so early in the season.

"This is kind of unusual," Winkle said. "But, you know, it makes it more interesting."

Winkle and his crew passed through the survey area twice, dumping the trout they caught into a holding pen after each round.

Then, they measured and weighed each fish, being careful to keep their skin wet and not leave them out of the water too long.

Clear Creek is mostly inhabited by wild brown trout, introduced to the state in the late 1800s. But CPW does stock other species, and sometimes a surprise pops up.

"Rainbow," Winkle called out, catching the distinct pink stripe running along the fish's side.

"Nope, Cutbow," said technician Ariel Demarest.

"We had a couple of cutbows and a couple of little teeny, tiny rainbows, so that's actually very encouraging," Demarest said later.

Winkle said the survey is also an important tool to track populations over time. He said brown trout have thrived in this part of the creek since the Argo Mill installed a treatment plant in 1995 to remove mining waste from the stream. Further up the creek, another treatment plant started cleaning heavy metals from the water a few years ago, and the trout population there is beginning to rebound as well.

"As part of my job as a fish biologist, I want to maintain fish populations not just for the intrinsic value in the ecosystem, but for anglers and the next generation of anglers," Winkle said.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS | Science is Cool