VERIFY – YOU’VE GOT QUESTIONS, WE’LL FIND ANSWERS

A 9NEWS project to make sure what you’ve heard is true, accurate, verified. Want us to verify something for you? Email verify@9news.com.

THE QUESTION

President Donald Trump on Thursday declared the opioid crisis a nationwide public health emergency, saying the U.S. must confront "the worst drug crisis in American history."

Trump called attention to the growing epidemic that resulted in 64,000 American overdose deaths last year, 175 every day and seven every hour.

The president said, "the federal government is aggressively fighting the opioid epidemic on all fronts."

The 9NEWS Verify team looked into the opioid crisis in our own state.

WHAT THE DECLARATION MEANS FOR CO

Nationally and in Colorado, opioid use disorders have become a substantial public health concern.

Robert Valuck, a pharmaceutical professor from the University of Colorado, and the director of the Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention, said it was important for the situation to be declared a public health emergency.

“We’re already doing some things already, and so I think time will tell how effective this declaration is and how much it really helps, especially in states like in Colorado,” Valuck said.

Thursday’s designation grants specific powers to the administration, which would allow patients to receive medically-assisted treatment for opioid addiction through telemedicine, grant more flexibility in hiring substance abuse specialists temporarily, make Dislocated Worker Grants available to people with opioid addiction and tap the Public Health Emergency Fund.

Valuck said these are promising things, most of which he said were already being done - but not nearly to the scope or scale the nation needs.

“We’re doing things to ramp up MAT (medically-assisted treatment), there are these telemedicine approaches that are being used to try to link providers, you know that may be out in a rural area, with a substance abuse treatment specialist who’s in an urban area,” Valuck said. “So those things do exist in pockets, it’s really about how can we ramp this up in a lot larger way.”

He described hopefulness for more resources dedicated to the problem and the need to ramp up treatment capacity to fill the gap.

“Eighty to 90 percent of people who have a use disorder and want or need treatment can’t get it… we need more people trained to provide treatment, we need more places for them to go,” Valuck said.

He said there needs to be an improvement in getting naloxone, a drug that works to reverse overdoses, into the hands of the public in an effort to prevent overdose deaths. Safe disposal of leftover medication was also a concern of his.

“More than 70 percent of people start with leftover meds in the medicine cabinet from somebody else,” Valuck said. “We know we have to try to get rid of all that medicine that’s left over and really it’s not doing anybody any favors just by sitting there. It’s really a danger.”

According to a Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing opioid use overview from March 2017, opioid overdose deaths increased from 2000 through 2015.

“From 2000-2015, there have been 10,552 drug overdose deaths among Colorado residents with rates rising in almost every year,” according to a Colorado Department of Public Health & Environment health watch from Nov. 2016.

In 2015, about one Coloradan died every 36 hours from opioid overdose according to the CDHCPF report.

“In 2015, Colorado reported 329 deaths related to prescription opioid overdose (PDO), making up 38.8 percent of all drug-related deaths in the state,” according to the CDPHE.

Valuck said Colorado is “in the middle of the road” when it comes to overdose deaths – but describes other numbers as “really scary.”

He said Colorado is among the higher states in self-reported non-medical use, which means people who admit to using an opioid either that was someone else’s, or was something they had from before.

“In 2012, we were number two in self-reported non-medical use, now we’re down in the mid-teens, 15 -17, in that range, which is better,” Valuck said.

But, he still expressed concern because the population in Colorado seems to have lower risk perception.

“We are worried that people here are willing to try those things, and not think that it’s quite as risky as it is, and they’re willing to try it, and that we will have a higher rate of addiction,” Valuck said. “We’re concerned about that, and then people don’t end up non-medically using, then having a use disorder, then having overdoses and then dying.”

OPIOID AND HEROIN CORRELATION

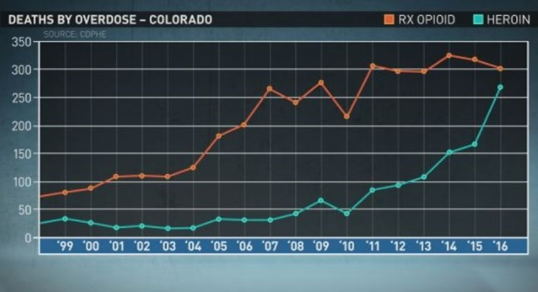

The opioid overdose deaths decreased 6 percent in 2016 in Colorado, however, heroin overdose deaths increased 23 percent in 2016, according to the overview.

As the 9NEWS Verify team previously reported, the number of Coloradans dying from prescription opioids dropped from 338 in 2014 to 300 in 2016, according to data from the CDPHE.

The bad news is the number of people who overdose each year on heroin rose from 151 to 228 during the same period – creating a steady rise in the overall number of overdoses.

“People will move around from one to the other, whatever they are able to obtain, and the total number of opioid overdose deaths has continued to rise from 472 two years ago, to 504 a year ago,” Valuck said. “So, we’re still increasing at about 5 percent a year when you put them all together.”

He said the key to ending this cycle is treatment.

“There’s also some data suggesting the heroin problem was already getting worse… the heroin prices were dropping, heroin supplies were going up, all that has been happening for several years” Valuck said. “It’s hard to say did clamping down on prescribed opioids cause the heroin jump, or did they both just kind of happen at the same time?”

GEOGRAPHIC VARIABILITY

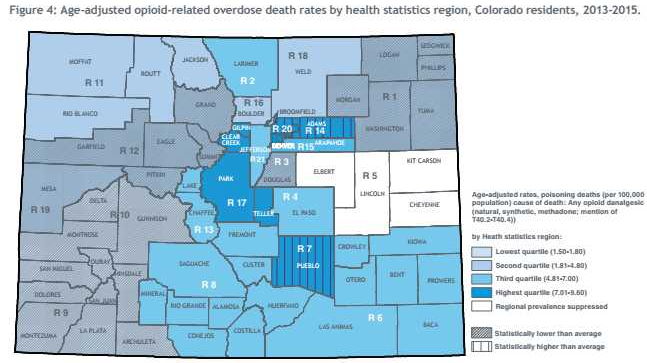

The southeast corner of the state had higher rates of both opioid-related and heroin-related overdose deaths from 2013 through 2015; but, the highest rates tended to be in more urban regions, according to the CDPHE.

As the CDPHE map below shows, the regions with the highest rates for opioid-related overdose deaths from 2013-2015 were Pueblo, Adams and Denver.

During 2016, 9 percent of prescriptions were opioids, whereas, in 2013, 11.3 percent of prescriptions were opioids, according to CDHCPF. During 2013, 710 providers prescribed high dose opioids for 30 plus days, and during 2016, 288 providers prescribed high dose opioids for 30 plus days.

The overall national opioid prescribing rate decreased from 2012 to 2016, according to the CDC.

“In 2016, the prescribing rate had fallen to the lowest it had been in more than 10 years at 66.5 prescriptions per 100 persons (over 214 million total opioid prescriptions),” according to the CDC.

Although that’s an improvement, still in about a quarter of U.S. counties, enough opioid prescriptions were dispensed for each person in that county to have one.

The following map shows the 2016 prescribing rates in Colorado counties.

The effects of opioid addiction can be felt by Coloradans of all ages. Mothers who abuse opioids during pregnancy can potentially birth drug-addicted babies – neonatal addiction is up 91 percent in Colorado, according to the CDHCPF.

BOTTOM LINE

The effects of the national opioid crisis are without a doubt being felt in our own state of Colorado.

Around 224,000 Coloradans misuse prescription drugs every year, according to CDPHE.

"No part of our society – not young or old, rich or poor, urban or rural – has been spared this horrible plague," Trump said.