VERIFY – YOU’VE GOT QUESTIONS, WE’LL FIND ANSWERS

A 9NEWS project to make sure what you’ve heard is true, accurate, verified. Want us to verify something for you? Email verify@9news.com.

THE QUESTION

Every place has its local lore; legends passed down in stories. But are those stories actually true?

9NEWS’ verify team decided to find out. It’s a new, occasional series we’re starting called Verify – Legends.

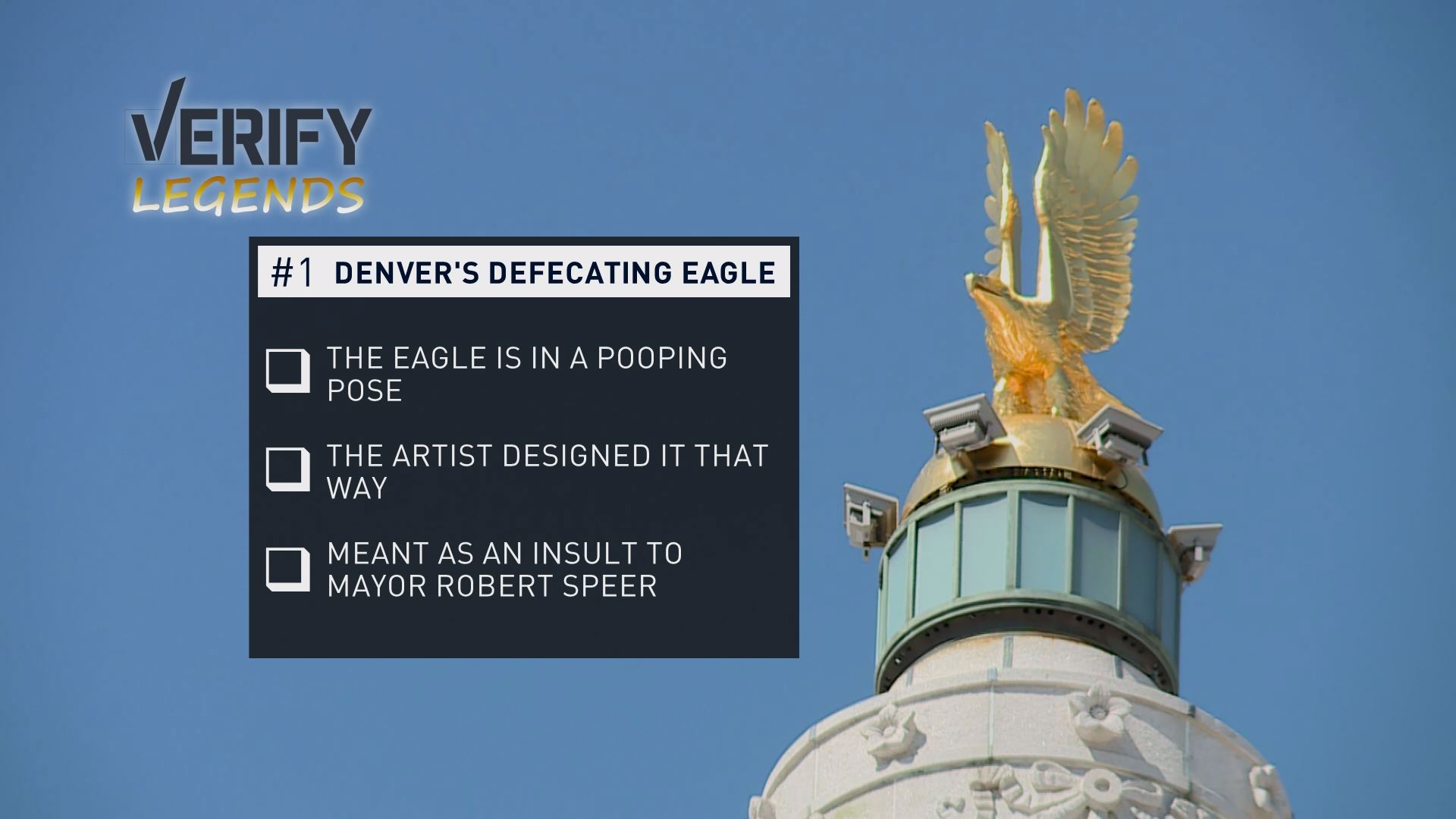

The first legend the team tackled surrounds an icon in the heart of Denver: The eagle statue that sits atop Denver’s City and County Building.

The legend – propelled by politicians, business people and the Denver Free Walking Tour -- claims the eagle’s sculptor exacted revenge on Mayor Robert Speer by designing the eagle in a defecating position.

The Verify team went looking for an answer and found an incredible story. You can watch it in the video above.

WHAT WE FOUND

To crack this myth, the Verify team talked to a bird expert at the Denver Zoo, the grandson of the lead architect and combed through hundreds of pages of public and private records.

The first question is the easiest to answer: Is that what an eagle looks like when its relieving itself?

For the answer, we traveled to the Denver Zoo and asked John Azua, the Zoo’s curator of birds for the last 20 years.

He said it’s possible for an eagle to poop in that position because they can go to the bathroom from almost any position – even while in flight.

Our Verify team saw the zoo’s male eagle poop while perched on a branch during our interview. The eagle lifted his tail feathers slightly, but that was it.

What does Azua think the eagle on top of the city and county building is doing?

“To me that eagle by the sculptor looks like it’s taking off not pooping,” Azua said. “And there’s so many poses an eagle could take to poop. That’s just one of them. But I think that eagle is taking off.”

OK, so there’s no one way an eagle defecates, but we wanted to know whether the sculptor thought he smited Speer by creating an eagle forever unloading on the building.

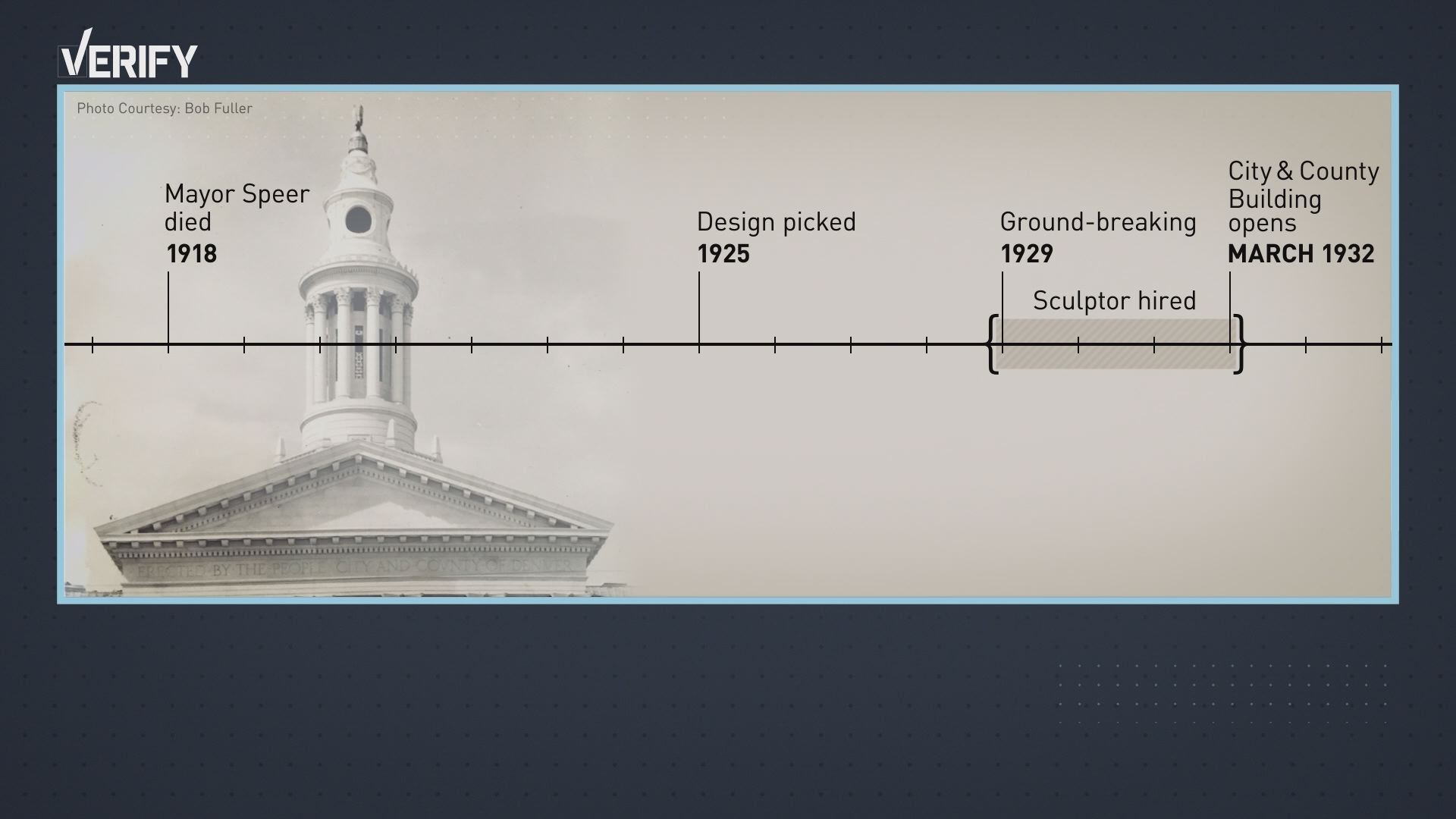

It's true Speer had the vision for a great civic center downtown with a big park between the Capitol and Denver's city hall. But the notion he ticked off the sculptor falls apart when you look at the building’s timeline.

The city chose the winning design in 1925 and broke ground in 1929. The sculptor, Joseph Nicolosi, was picked sometime between the ground breaking and the building’s completion in 1932.

If it sounds like that’s long enough to get fed up with Speer, there’s one, small problem. The mayor died in 1918 – almost seven years before anyone knew there would be an eagle on top of the building.

Nicolosi likely never even met Speer. He was a 25-year-old Italian immigrant when Speer died, and he never lived in Colorado.

Mayor Benjamin Stapleton shepherded the building through its design, funding and construction.

Is it possible Nicolosi or someone else involved in the building’s design got fed up with Stapleton?

The city has scant few records from that period. And the Denver Public Library only had half a blueprint from the original drawings that didn’t show the top of the building.

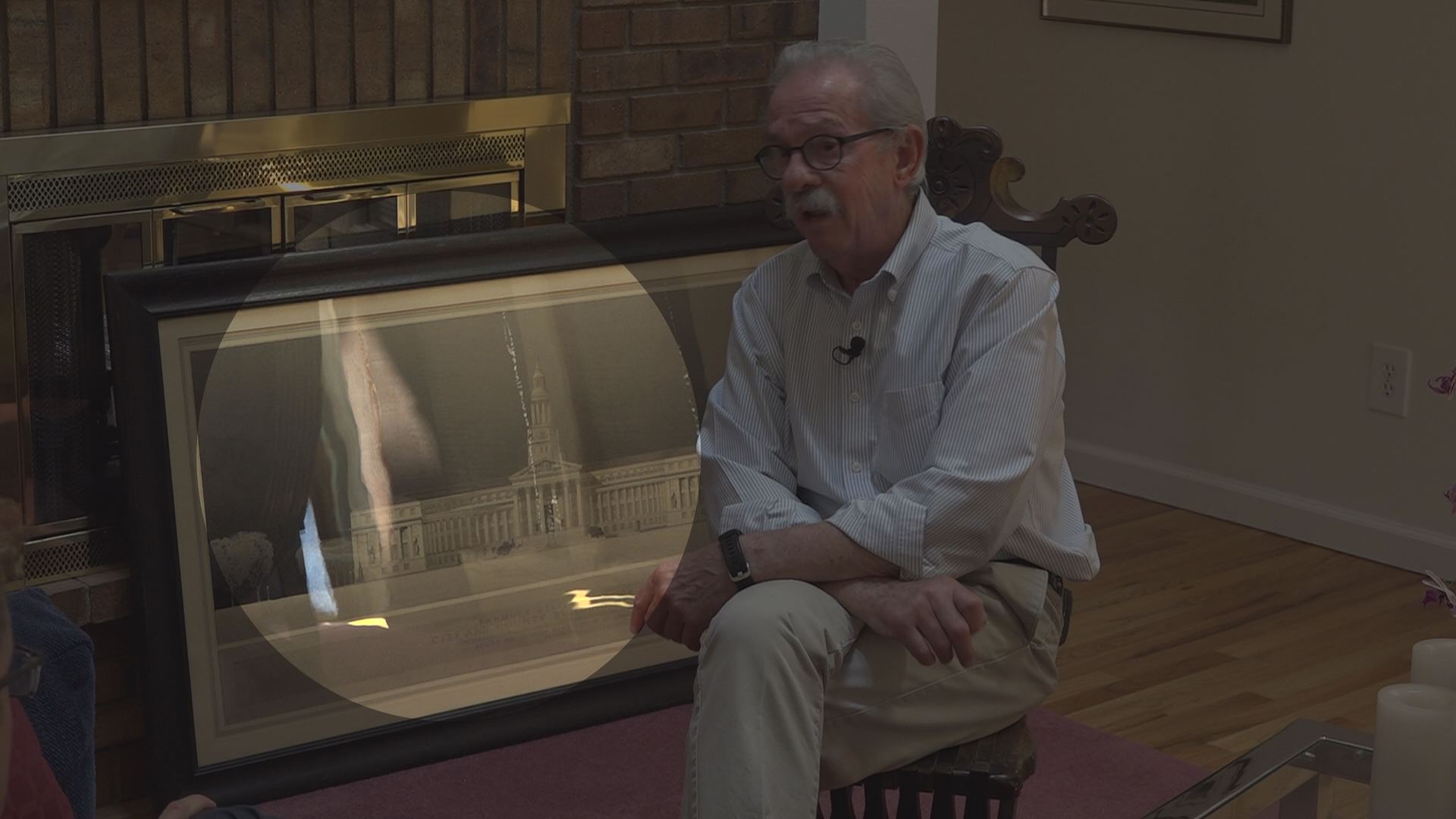

But we found something better. The lead architect’s grandson.

“I have never heard of the eagle poop rumor,” Bob Fuller said.

Fuller’s grandfather, Robert Fuller, led the Allied Architects Association. It was a group of Denver architects who got together to bid on the city and county building project.

No local firm was big enough to take on the project by itself, Fuller said.

The Allied Architects kept detailed records of the project. Its ledgers contain everything from which companies were in the running to paint the building down to how much money the architects spent on towels for the office.

And those records have been sitting in cardboard boxes in Fuller’s garage.

Our Verify team combed through those boxes and read the Allied Architects’ ledger from cover to cover to see whether anything might point to this legend being true.

Here’s what we found:

City Council approved the Allied Architect’s plans for the building June 29, 1925. They broke ground on March 26, 1929.

Fuller said that’s normal for a project of this size because the architects had to produce a mountain of detailed drawings and work with engineers to bring the initial design to life.

The ledger shows the architects hiring the first, main contractor in February 1929 – a few weeks before they broke ground.

The project sailed along until that October. That’s when the Great Depression hit.

“Which was a very awkward time to go into construction on this elaborate new municipal building,” Fuller said.

The building’s price tag was $4.6 million, and the city promised to pay the architects 6 percent in fees.

Suddenly, the city produced an “obscure law” saying architects couldn’t practice as an association and declared the contract invalid, Fuller said.

That’s true. The ledger and news clippings from the time show the city stopped paying the architects and took them to court.

The lawsuit went all the way to the Colorado Supreme Court, which decided in the city’s favor in June 1931.

The architects lost about $84,000 or $1.3 million in today’s dollars, and the city took the project from them.

That sounds like bad blood.

But Robert Fuller never discussed it with his grandson.

“My grandfather was a very professional and somewhat distant man. He was not the warm, fuzzy grandfather that we see nowadays,” Fuller said. “He was strong and professional but somewhat reserved personality.”

The architects’ meeting minutes don’t mention any plans for the sculpture either.

It started to sound like the myth was unsolvable, but then we found the answer in Fuller’s living room.

Leaning against Fuller’s fireplace during our interview was the original drawing of Denver’s City and County building. It’s signed and dated June 30, 1925.

When you look at top of the building, you see an eagle with its wings up, pointed towards the sky.

The eagle looked the same in the photographs Fuller had of the model the architects built as part of their presentation to the city.

“Well, I think the rendering probably has more to do with the reality of the situation than anything,” Fuller said. “That eagle in that posture well predates any of the financial issues that the architects went through, or any possible bad blood during construction or unhappy politicians.”

The architects were also proud of their work.

During their final meeting in January 1934, the minutes describe the members as men of vision who should be proud of the building and their hard work to create it.

And rather than keeping the final $3,400 payment from the city, the architects started a scholarship fund.

Today, the Architectural Education Foundation is worth more than $3 million and gives out several scholarships each year.

“The whole hope was that it would in some way, that little bitty sum born out of conflict, would amount to a good thing ultimately, which it has,” Fuller said.

A more realistic theory for why the eagle has its wings up is the architects copied the city seal, which had already been around for two decades. It shows an eagle taking flight with its wings pointing towards the sky.

BOTTOM LINE:

- The eagle isn’t in a defecating position because there is no one way an eagle relieves itself.

- (You can see how the Denver Zoo experiment ended in the video above, as well as this entire story.)

- Speer couldn’t have fought with the sculptor because he died years before the city hired anyone to work on the building.

- And despite a serious legal battle between the city and the architects, the eagle’s design remained unchanged from its original iteration.

We found nothing to support this legend, and holes in every part of the story. We're calling it false.

The legend of Denver's defecating eagle is all kinds of fun, but it stinks, wings up to high heaven.