VERIFY LEGENDS – YOU’VE GOT STORIES, WE’LL FIND ANSWERS

A 9NEWS project to make sure what you’ve heard is true, accurate, verified. Want us to verify something for you? Email verify@9news.com

Editor’s note: Watch the rest of the story below.

THE LEGEND

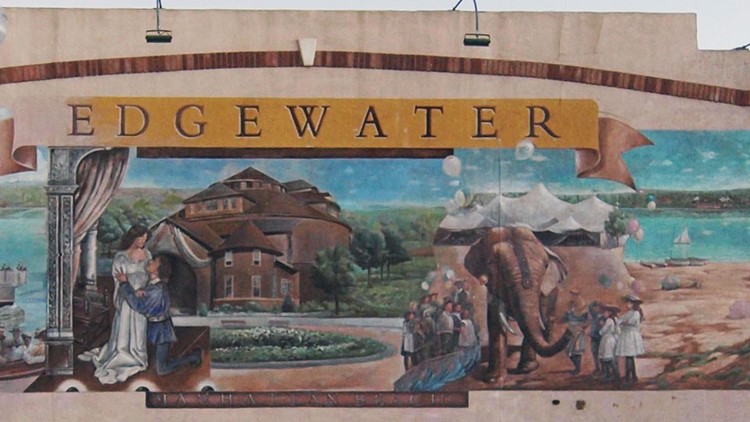

On a warm, sunny Sunday afternoon 5-year-old George Eaton climbed into a basket perched on the back of Roger, the elephant.

Roger was the star attraction of the Manhattan Beach amusement park located on the northwest corner of Sloan’s Lake. His job that fateful day in July 1891 was to ferry baskets of children around the park.

The trips were going well until about 4 p.m. – the time George Eaton and four other boys climbed inside Roger’s basket.

Some people said a rising hot air balloon scared Roger. Others thought the rush of people to see the balloon spooked him. Whatever the reason, Roger bucked and George Eaton fell out of the basket.

Roger’s trainer, Fred Knight, tried to control the panicked pachyderm. But the elephant struck him in the face, breaking his nose and cutting his forehead.

Roger swerved and crushed 5-year-old George Eaton to death in front of his parents and younger brother.

According to the legend, Knight finally gained control of Roger and led him to the swampland outside the park.

Then, the trainer shot Roger and buried him beneath what is now an abandoned King Soopers grocery store or the parking lot for the Edgewater City Hall complex.

Books, news articles and Edgewater residents dispute where Knight buried Roger, but they all believe the elephant killed a child and the amusement park staff killed the elephant.

Rocky Mountain News article from July 6, 1891 by 9news on Scribd

What if they’re wrong?

What if Roger didn’t kill George? What if the trainer didn’t kill Roger? That’s what the 9NEWS' Verify team set out to discover: What really happened to Roger, the elephant.

GEORGE EATON’S UNTIMELY DEATH

The legend of George and Roger sounds like a grim piece of history, but to Rex Eaton it’s a family story.

“George Eaton was my father’s brother,” the 81-year-old told 9NEWS from an armchair in his Tucson, Arizona home.

He grew up with the story of an uncle who died tragically under the foot of an elephant.

“Maybe my grandmother didn’t like talking about it because I don’t recall her ever saying anything about it … ,” Rex Eaton said. “All of the story I got from my father.”

As a kid, he thought maybe his dad was pulling his leg with this story.

“It’s very unusual,” Rex Eaton said. “How many people get killed by an elephant?”

But the more he heard it, the more he believed.

Newspapers across the country – including the New York Times -- ran articles after George Eaton died:

“Oh,” [George Eaton’s father] sobbed. “I can’t believe it. He was such a bright boy, our oldest. How we loved him and how we planned for his future. I don’t know what to do. I can’t realize what has happened. Ten thousand grounds like these couldn’t pay us for his loss.”(Rocky Mountain News: July 6, 1891)

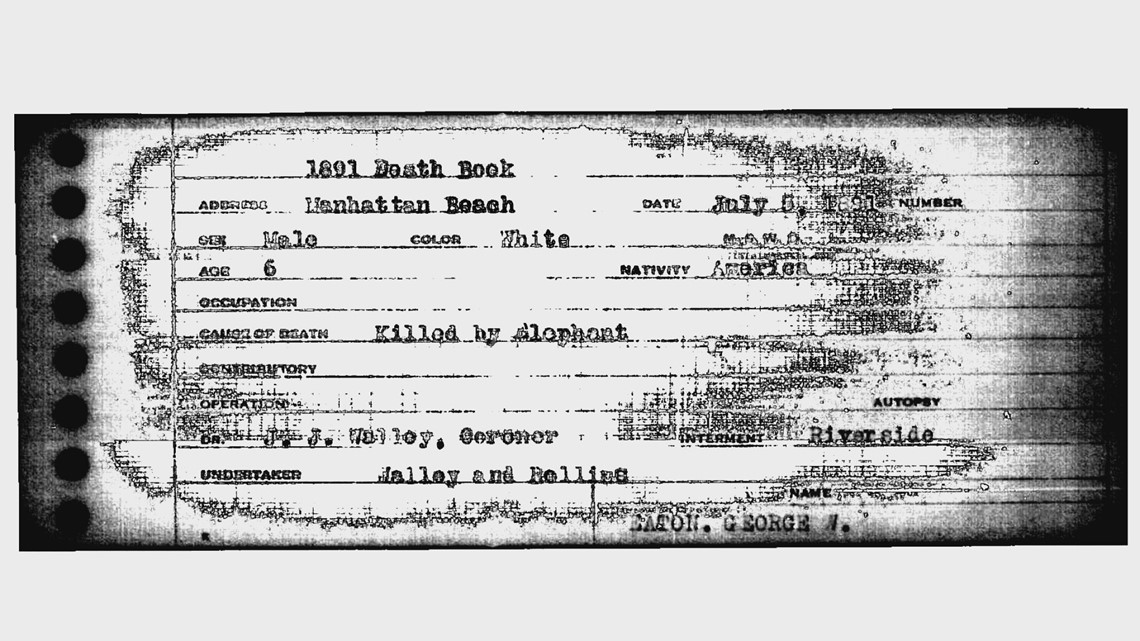

George Eaton’s death record from Denver Hospital was also digitized. It lists his cause of death as “killed by elephant.”

It’s true. Roger, the elephant, crushed George Eaton to death in front his friends and family.

ROGER’S PUNISHMENT

Rex Eaton’s father never mentioned Roger’s fate when he talked about his older brother.

“Now, I did hear also that after the incident, my grandfather, the child’s father, he wanted to kill the elephant,” Rex Eaton said. “He just went crazy. Wanted to get a gun and kill the elephant.”

Pressley Eaton was angry. He wanted someone or something to pay for the death of his firstborn son.

“But some other men talked him out of it, or held him back or kept him from doing that,” Rex Eaton said.

Pressley Eaton didn’t kill Roger.

But what about Knight, the elephant trainer? Somebody shot Roger, right?

“It didn’t happen,” local historian and amusement park author Dave Forsyth said.

News clippings from the Rocky Mountain News, the Denver Post, the Denver Republican and The Daily News: Denver prove Roger was alive and well at Manhattan Beach for at least two years after the accident.

In September of 1891 – just months after Manhattan Beach opened -- the park found itself in a legal battle over its animals.

Elitch Garden’s owners had bought Manhattan Beach’s chattel debt, a loan taken on a piece of movable property like furniture or animals.

When the Manhattan Beach stopped paying on the debt, Elitch’s sent a small army of men down to Manhattan Beach to take the animals by force during the pre-dawn hours of Sept. 11, 1891.

Manhattan Beach’s employees defended the park, and the case found its way to District Court Judge David Graham.

“[Roger] was part of the court case,” Forsyth said. “He was one of the animals that they were not going to let go.”

Graham ruled in favor of Manhattan Beach. He said the animals would stay there until they were sold to pay the park’s mounting debts.

FINANCIAL PROBLEMS PLAGUE THE PARK

In February of 1892, a paper called The Daily News: Denver sent a reporter to see how the animals handled their first Colorado winter. Consumption killed several monkeys and ostriches.

“Old Roger, the elephant who was the innocent cause of the little boy’s death last spring, didn’t seem to have outgrown sorrow for the sad event … ” (The Daily News: February 23, 1892)

And the reporter makes another important point: Feeding an elephant isn’t cheap.

“The elephant is an expensive brute to shove off on a trustee who is trying to keep expenses down, as his menu consists of five small bales of hay and half a bushel of grain daily.”

The trustee, William Todd, struggled to care for the animals who lived at Manhattan Beach, according to court documents 9NEWS found at the Colorado State Archives.

An 1892 court case against the park’s owners explained how Todd borrowed “a large sum of money” to “keep the animals from starving and to put the premises in a proper state of repair.”

But Manhattan Beach didn’t sell its star attraction right away. Newspaper articles placed Roger at the park during the summer of 1892.

“The elephant, had his fill of peanuts and popcorn, and he seemed to be delighted to see his friend again after their long winter exile.” (Rocky Mountain News: May 16, 1892)

And Manhattan Beach advertised Roger’s annual bath in the Rocky Mountain News later that summer.

In 1893, a district court judge ordered a new trustee to sell the park’s monkeys to pay off some debts. 9NEWS found five additional court cases where vendors went after the park for not paying its bills.

The local papers don’t mention Roger after the fall of 1893, and advertisements for Manhattan Beach’s 1894 opening make no mention of what was once the park’s star attraction.

Then, the trail goes cold.

The elephant trainer and his wife left Denver in 1894, according to address records and census data. Fred and Della Knight eventually settled in St. Louis, Missouri.

But what about Roger?

“My suspicion would be that he was sold,” Forsyth said.

HOW TO SELL AN ELEPHANT

Elephants – even those with spotty pasts – fetched thousands of dollars in the late 1800s.

“There are more than a few elephants who had records of having killed multiple people in those days,” said Nigel Rothfels, a historian who wrote a book about elephants in captivity. “They would just show up somewhere else, often with a different name. They might be one or two years in one outfit and then go on to another. It can be very difficult to actually track their lives.”

But it’s not impossible.

The first clue came from an article written the day George Eaton died.

“Mr. [William] Conklin, the manager of the zoo in Central Park, who is in the city says he has known Roger for fifteen years. The big animal was in his charge for five years. He has never known Roger to become alarmed before and says the elephant is of the kindest disposition.” (Rocky Mountain News: July 6, 1891)

William Conklin ran the Central Park Menagerie in New York City. It’s a role Conklin had for more than a decade at the time of George Eaton’s death, and most likely where he met Roger.

The 1890s meeting minutes from the Board of Commissioners of the NYC Department of Public Parks still exist, but they don’t show the zoo selling an elephant.

What they revealed was something we hadn’t considered: Manhattan Beach might never have owned Roger.

The meeting minutes list an elephant belonging to Circus Owner William Washington Cole leaving the zoo eight days before Roger arrived in Denver.

Why is the date important?

“Occupying a car by himself is the war elephant, Roger, one of the best of his kind. He is a docile looking brute, though his eight-day overland trip and necessary close confinement has made him a little nervous.” (Rocky Mountain News: June 23, 1891)

ANIMAL SWAPPING

It wouldn’t happen today, but zoos and circuses traded both animals and trainers back in the 1890s and early 1900s.

In fact, it was common for circuses to loan their elephants – especially the disobedient ones – to zoos and amusement parks.

“Later Mr. Bailey came down and told me to chain him to an old elephant and take him up to Central Park – that he was going to make the city a present of him,” lion tamer George Conklin wrote in his book “The Ways of the Circus.”

These loans didn’t always end well.

“In a few years, the elephant grew so ugly that it was thought best to kill him,” George Conklin wrote.

And when the Central Park Zoo killed that elephant, which it named Tip, it didn’t happen quietly.

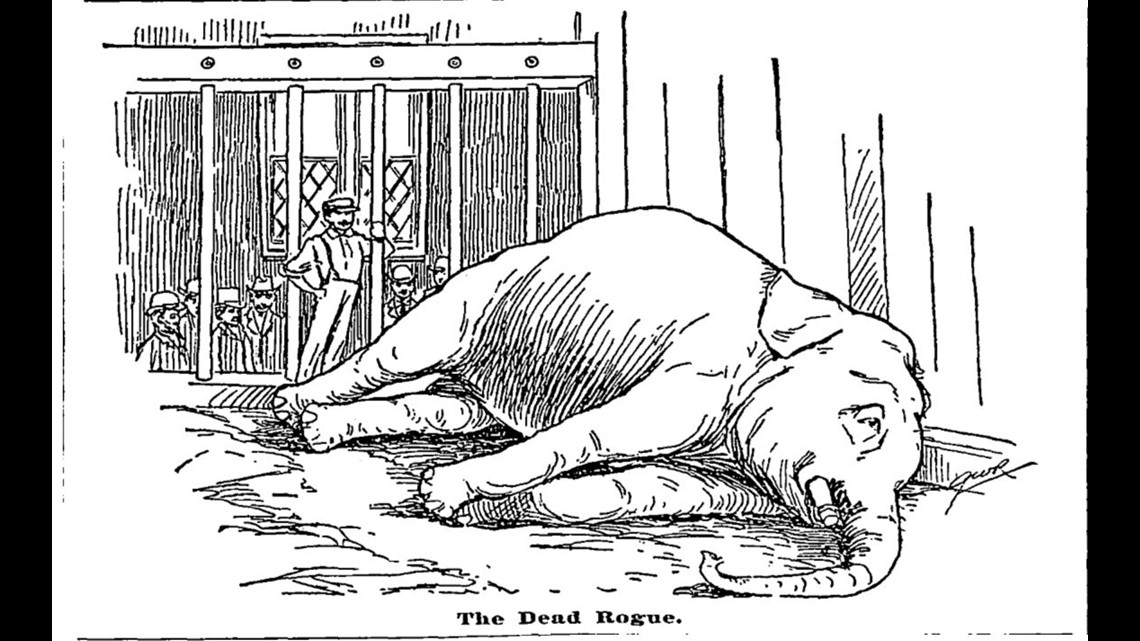

KILLING AN ELEPHANT

“There were a lot of amusement parks and amusement places that would make big spectacles out of executing rogue elephants,” Forsyth said.

Tip’s death made national headlines. And even though he “murdered several keepers,” people still wondered “whether so valuable an animal under another keeper might not be made manageable,” according to the New York Times.

In Baltimore in 1898, Frank Bostock euthanized an elephant named Sport by hanging.

“Murderous Mary” also went to the gallows after she stomped her handler to death.

And there’s actual video of an elephant named Topsy being electrocuted to death on Coney Island in 1903.

Manhattan Beach couldn’t have quietly executed Roger – especially when people viewed George Eaton’s death as an accident.

“Roger, the elephant, was the star of the Manhattan Beach zoo,” Forsyth said. “Everyone wanted to ride on him. Everyone wanted to see him.”

It was not, however, a big deal for an elephant’s owner to move him or her onto another show or zoo. 9NEWS couldn’t find a single story in the New York Times archive for any of the elephants who left the Central Park Zoo in the late 1800s or early 1900s.

BOTTOM LINE

9NEWS verified that Manhattan Beach didn’t kill Roger for crushing George Eaton. The elephant continued to eat peanuts and entertain visitors for at least two more summers.

“Why would you blame the elephant?” Rex Eaton said. “Why would you blame the child that released the balloon? It was just something that happened.”

The most likely ending to Roger’s story is that he went to another zoo, park or circus and got a new name.

“It seems unlikely that the animal would have come with a name like Roger,” Rothfels said. “Names like that happen when the animal is acquired and the animal is named after someone local (a wife, a friend, a benefactor).”

Whether Denver’s infamous elephant died of old age or was put to death somewhere else remains a mystery.

There aren’t elephant bones underneath a parking lot in Edgewater, but there is part of this legend resting in Colorado soil.

Search the graves at the back of Riverside Cemetery, and you’ll find a lone plot with a small, tilted headstone that reads killed at Manhattan Beach on July 5, 1891 at five years, 11 months, and 16 days old.

It’s the final resting place of George Eaton.