Children who were brought into the country illegally could have a path to citizenship if a bill introduced Friday by Rep. Mike Coffman (R-Colorado) and nine other lawmakers passes.

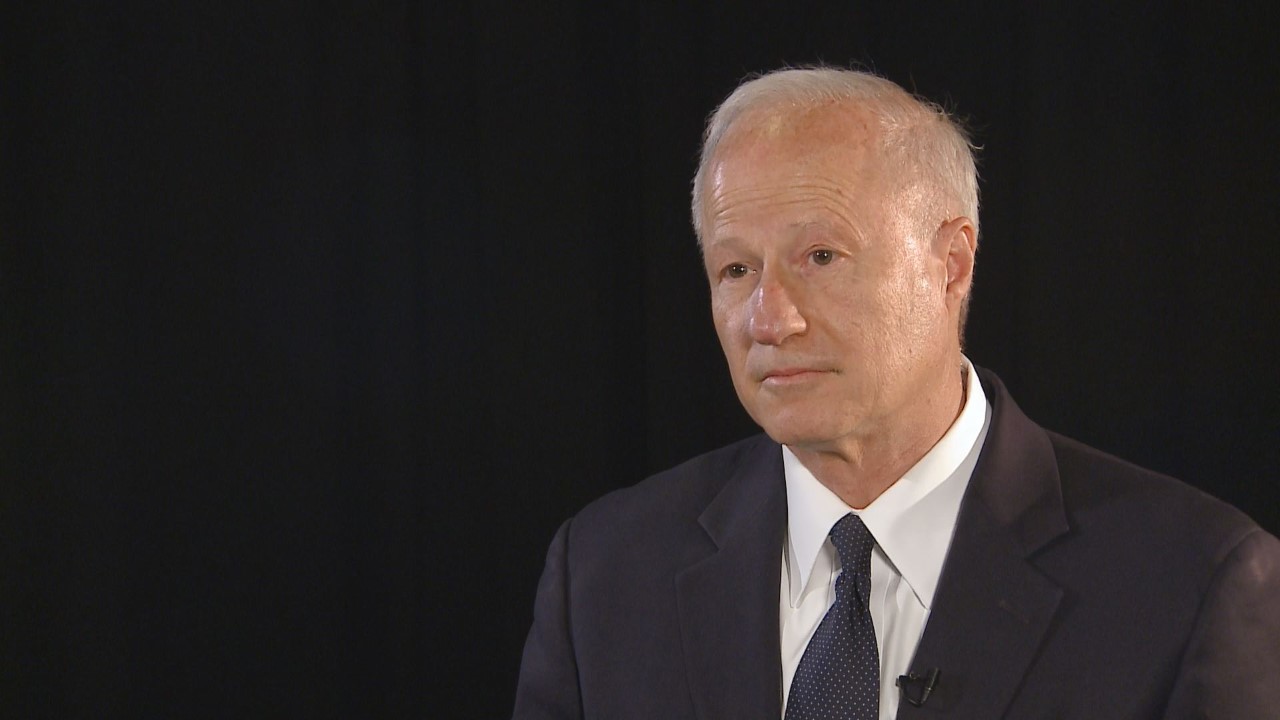

"I think it's very important to chart a course for these young people who were taken to the United States, it wasn't their decision. They grew up here. They went to school here. Often times they know no other country ... ," Coffman told 9NEWS. "They ought to have a path to permanent residency and then they could certainly apply to citizenship."

The bill is called the Recognize American Children Act and creates three pathways towards legalization for kids who meet specific criteria.

- The child was brought to the U.S. before January 1, 2012.

- He or she was younger than 16 when he or she crossed the border.

- Has lived in the U.S. for at least the last five consecutive years.

- Aside from traffic violations, he or she has no criminal convictions.

- Is now at least 18 years of age and has a high school diploma or equivalent degree.

- Has been accepted into a post-secondary program, plans to join the military or has a valid work authorization.

If the child meets these requirements, he or she can apply for what’s called a conditional legal permanent status that lasts five years.

If they want to extend that status for another five years, they must meet a second set of requirements.

- Graduate from an accredited college or vocational school.

- Or serve three years in the military with an honorable discharge.

- Or work for 48 months during the five-year period.

- Continue to demonstrate “good moral conduct” as defined by immigration law.

Then, at the end of 10 years they become eligible to apply for legal permanent residency – putting them on the path to citizenship.

The bill bears some key similarities to President Barack Obama’s failed DREAM Act and his executive order blocking the deportation of “childhood arrivals” or DACA.

All these programs require applicants to have been younger than 16 at the time they entered the U.S. And all require applicants to pursue higher education, work or serve in the military while maintaining a clean criminal record.

The big difference between this bill and the DREAM Act is that the new proposal creates a path for those who choose to work rather than attend college or enter the military.

If Coffman’s bill passes both chambers, it isn’t clear whether President Donald Trump would sign or veto it.

At a press conference in February, Trump called the deportation of children brought to the U.S. illegally by their parents a “very, very tough subject.”

"To me, it's one of the most difficult subjects I have because you have these incredible kids, in many cases, not in all cases,” Trump said. “And some of the cases, having DACA and they're gang members and they're drug dealers, too. But you have some absolutely, incredible kids, I would say mostly.”

The Department of Homeland Security also issued a memo in February that appeared to protect Obama’s executive order blocking the prosecution of “dreamers.”

However, it states Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) will deport any undocumented immigration it catches.

Coffman's confident Trump would sign it if the bill's allowances for "youthful indiscretions" are "tightened up."

"I think the bill goes a little too far in that context," Coffman said.