DENVER — History Colorado's Center for Colorado Women’s History, at the Byers-Evans House Museum in downtown Denver, decided last year to find out more about the women who made an impact on Colorado's history. The museum selected three fellows to put together projects that share the untold stories of women who helped shape this state.

We sat down with Kelly Denzler, one of three fellows, who told us the stories of the four women she learned about who impacted her the most.

Denzler is a social studies and French teacher at St. Mary's Academy in Englewood. She gathered the information by talking to local historians and hopes to work this into the curriculum when kids learn about Colorado's history.

Some Kosuge

Some Kosuge arrived in the U.S. in the early 1900s as a picture bride.

Her granddaughter, Julie Ushio, said she never had met her husband before she arrived on June 11, 1912.

She came from a Samurai family and was highly educated for a woman of her time. She taught at a woman's high school in Fukushima before coming to America.

After marrying, Kosuge helped her husband with farming and raising 11 children.

Denzler found records that Kosuge wrote for a Denver area newsletter in Japanese hoping to make Denver more welcoming, and to establish culture and community within a city that didn't necessarily look like her or share her experience.

Ushio said her grandmother also wrote a newspaper column in the Colorado Times, as well as the Japanese newspaper under a pen name, Hakuye. The column's name was called "Woman's World." She eventually taught English at a Japanese school for the local Japanese community in the Merino, Hillrose and Ault area.

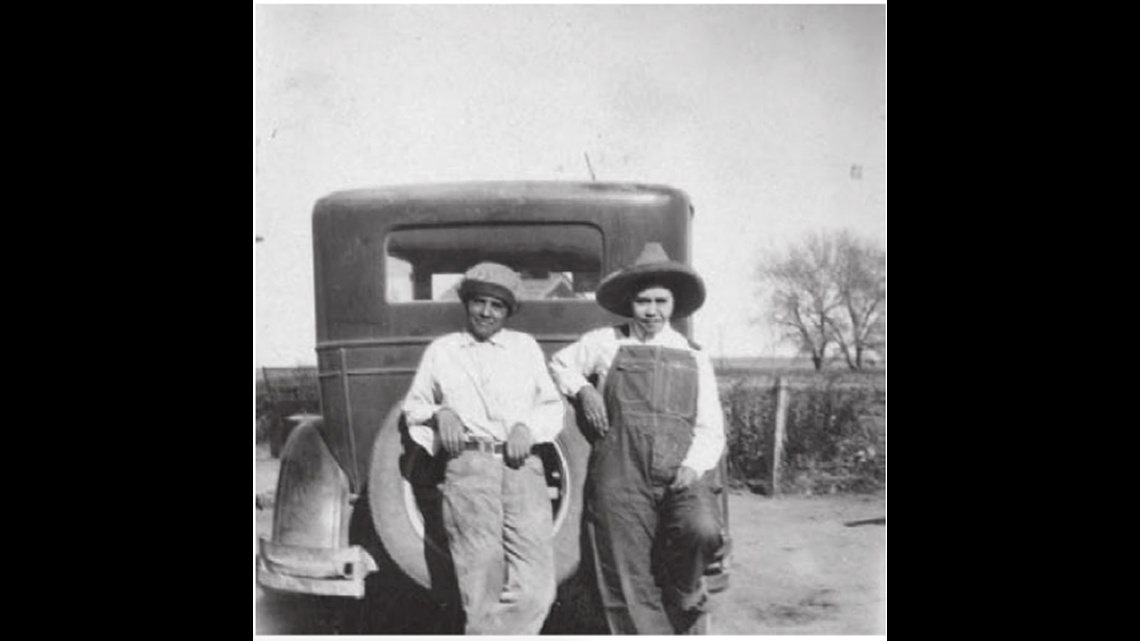

Jovita Ortega

Denzler said Jovita Ortega is a little more well known in certain communities.

She moved to Colorado in the early 1920s and helped her family farm a beet field in the northeast part of the state.

Her day would start at 3 a.m. with cooking breakfast for her family, and end after 11 p.m. when she was done with all of the day's duties.

Denzler said she found one story in which Ortega had to prop up the wash tub, where her baby daughter was sleeping, on chairs to avoid the rats in her house.

While Ortega did not have a lot of education herself, Denzler said it was tremendously important to her. Her children, who stayed in the Denver area, earned five masters degrees and a doctorate among them.

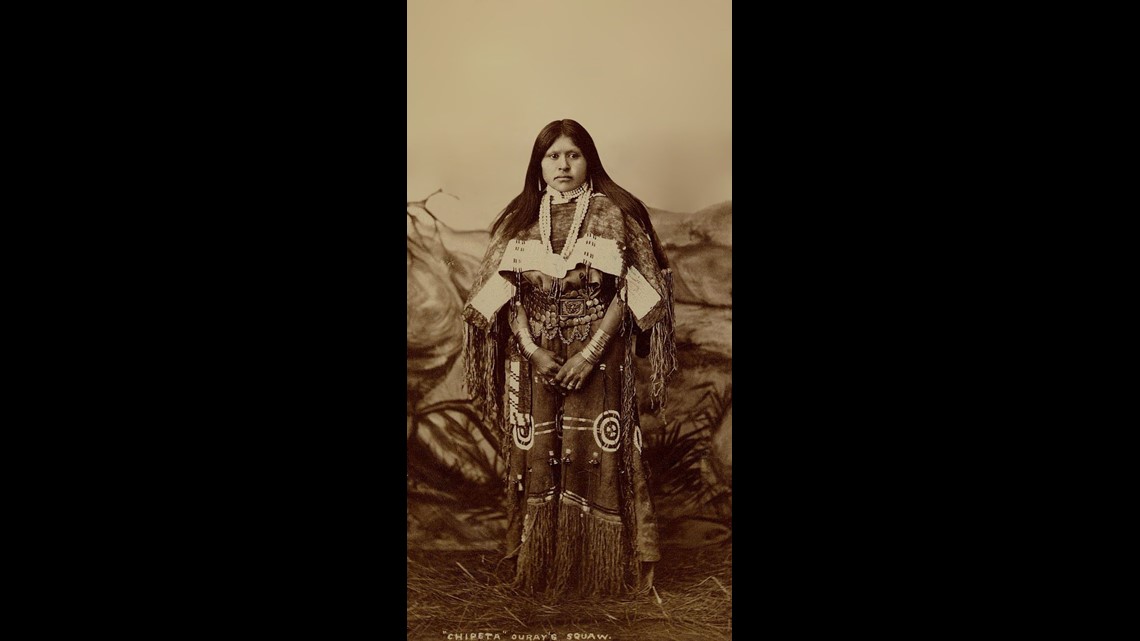

Chepita

Chepita became a respected leader in the Ute Indian Tribe.

Her story dates back to the late 1800s. Denzler found she was orphaned and adopted into the tribe.

She first met Chief Ouray when she started taking care of his baby son at 15 after the chief's wife passed away.

The two later became a couple and adopted several children.

Later on, Chepita went to Washington D.C. to testify in front of Congress on Native American relationships with the U.S. government, at a time that women didn't typically do that.

Denzler said she outlived the chief by 44 years and continued to build a legacy to the point that she became the inspiration behind folk stories.

Justina Ford

Justina Ford became the first Colorado African American woman doctor.

Denzler found that she wasn't allowed to join the Colorado or American Medical Societies because of racism. So instead, she practiced out of her home and visited patients at their homes through the first half of the 1900s.

Justina Ford knew not everyone could always pay her the $20 to deliver a baby, so she allowed her patients to barter, accepting food and other forms of compensation.

The Justina Ford House/Black American West Museum was named after her. According to the Denver Public Library, the home was her residence and office from 1912 until she passed away in 1952.

Denzler said when she died, at the age of 81, she had delivered more than 7,000 babies.

Denver Public Library said the house was moved around 13 blocks to its current location to save it from demolition.

----

History Colorado wants to continue researching and celebrating important women who made our state what it is. If you'd like to apply for their next fellowship, click here.

More from Next with Kyle Clark