ALAMOSA, Colo. — In a dusty and dilapidated cemetery where weeds grow among humble gravestones, Juliana Aragón Fatula stood next to her great-grandfather’s final resting place and shared a hidden family secret.

“My grandmother didn’t tell me any of this. My mother didn’t tell me any of this,” Aragón Fatula said of her great-grandfather’s past.

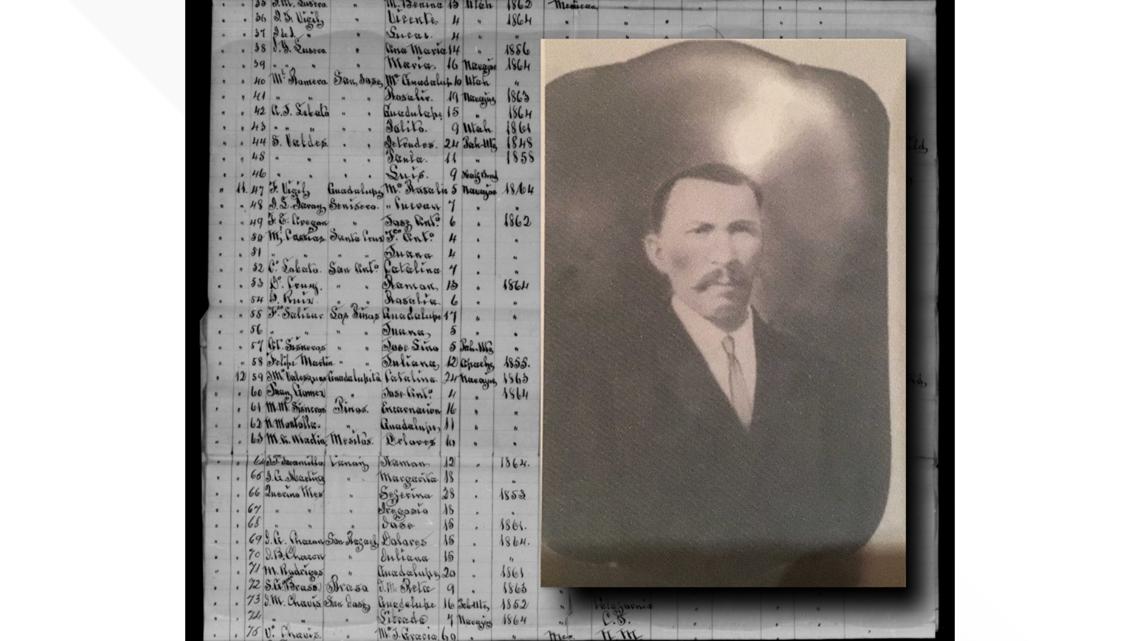

In an 1865 document titled “List of Indian Captives,” her great-grandfather, Jose Antonio Gomez, is named among dozens of other Native Americans who were “purchased” in Conejos County.

The list was created by Lafayette Head, a US Indian Agent, who would eventually become Colorado’s first lieutenant governor. Head traded and owned child slaves himself.

The revelation that her ancestor was indigenous and enslaved as a boy has profoundly influenced Aragón Fatula’s personal beliefs about her ethnic identity.

“My dad said we were Mexicans. Mexican Americans. My aunt said, ‘Oh, no we’re Hispanic. We are Spanish,’’ Aragón Fatula said. She said she has always been in touch with her indigenous roots and considers herself Chicana.

Aragón Fatula is among a growing group of people who are learning unexpected truths in their family tree thanks to a project called Native Bound Unbound.

The project brings a new team of historians together who search old documents, like baptismal and census records, to identify and catalog thousands of names of forgotten indigenous slaves in the Western Hemisphere.

Historian Dr. Estevan Rael-Gálvez, who has studied indigenous slavery for more than 20 years, put the team together thanks to a $1.5 million grant from the Mellon Foundation.

The goal is to eventually publish an open-source website where people can read stories and find names of their enslaved indigenous ancestors. The project is now in its second year of work and has already digitized and documented thousands of names.

“We are telling these stories because I think it not only troubles our sense of identity, but it also reveals the resilience and the complexity of how we think about identity,” Rael-Galvez said.

Slavery of Native Americans in southern Colorado, New Mexico

Rael-Gálvez sat down with 9NEWS in Colorado’s oldest town, San Luis, right across the street from the historical home of town founder Dario Gallegos. who owned multiple slaves.

“As we start to explore the records, you can’t open a baptismal book in this region and not find two or three enslaved individuals, in page after page, after page,” Rael-Gálvez said.

The history of enslaved peoples in southern Colorado and New Mexico region has largely been forgotten and sometimes suppressed because of shame, Rael-Gálvez said, adding the practice was “foundational” during colonialism.

Academics who research slavery in the southwest have estimated detribalized Native Americans made up one-third of the population in the late 18th century.

“There’s not a single Nuevomexicano, and by that, I mean this entire region in Colorado as well, who can not trace their ancestry back to at least one individual enslaved and indigenous,” Rael-Gálvez said.

Today the term genízaro, which refers to detribalized indigenous peoples of the era, is now embraced by descendants who are acknowledging their family history.

“There’s also a stigma in being indigenous, in that era, and we are now seeing people who are reclaiming that, and understanding the resilience and the power of what that means,” Rael-Gálvez said.

>Watch an extended interview with Dr. Estevan Rael-Gálvez, director of Native Bound Unbound.

The revelations of forgotten enslaved ancestors are challenging deeply personal perceptions among many descendants like Weston Archuleta, who grew up believing he was mostly of European ancestry.

Archuleta learned his great-great-great grandmother, Soledad, was an enslaved indigenous woman in Guadalupe, Colorado who was baptized at age six.

“To find out that way and that I had such a personal connection, it was very shocking. Especially being told you’re Spanish your whole life. Having that drilled into you and then having that obliterated. It’s almost freeing though,” Archuleta said.

Archuleta’s great-great-great grandmother was referred to as “criada,” which is one of the many slavery euphemisms Native Bound Unbound searches for in old archives.

While slavery was technically illegal in the Southwest, the practice was often hidden through softer terminology in recordkeeping, according to Rael-Gálvez.

A few of the terms Native Bound Unbound searches for in documents include:

- "Serviente" or servant

- "Genízaro/a" or Indian captive/detribalized Native American

- "Criada/o or reared as a servant or maid

- "Laborio" or laborer of Native American background

- "Rescatada/o" or rescued or ransomed

- "Yanacona" or servant who was indigenous

Justin Romero’s ancestor, Rosalia, is also named among the “purchased” list of Native Americans created by Lafayette Head.

Romero, who lives in Denver, said he always believed his family was predominantly Mexican, but the new information affirms what he called the “lore” of potential native roots in his family.

“I really like that word reclaim, because you almost get to reclaim, not just an identity but an origin. Like an origin that seemed kind of fuzzy,” Romero said.

“We knew there was a door there, but now that it’s opened, we could have never known what was on the other side,” Romero added.

Rael-Gálvez said one of the most surprising things about working on the project was seeing how pervasive and expansive indigenous slavery was throughout the Western Hemisphere.

Native Bound Unbound is not only focused on uncovering documents in North America but throughout the western hemisphere, from Brazil to the United Kingdom.

“It’s my job as a historian, as an anthropologist, to actually pull back those layers. Literally, we are doing that with archives. And I want people to recognize the beauty and the complexity from where they come from because it’s actually a powerful story,” Rael-Gálvez said.

At her great-grandfather’s gravestone, that powerful story has emboldened Aragón Fatula to continue embracing her indigenous roots as a Chicana.

She sang an indigenous song before the headstone during an interview with 9NEWS.

“I’m singing it to Mother Earth. I’m just praising the fact that I survived because my ancestor survived. If they hadn’t survived I wouldn’t be here,” Aragón Fatula said.

If you have any information about this story or would like to send a news tip, you can contact jeremy@9NEWS.com.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: 9NEWS Originals