DENVER — Democratic State Senator Chris Hansen finally told someone he is resigning his seat at the State Capitol. He told The Colorado Sun that he would resign from the State Senate on Jan. 9. The new session begins Jan. 8.

Now, the 75,000 people who voted for him last week also know.

Hansen just became CEO of La Plata Electric Association, a co-op based in Durango.

Colorado does not allow voters to pick state legislative vacancy replacements.

A handful of party insiders do.

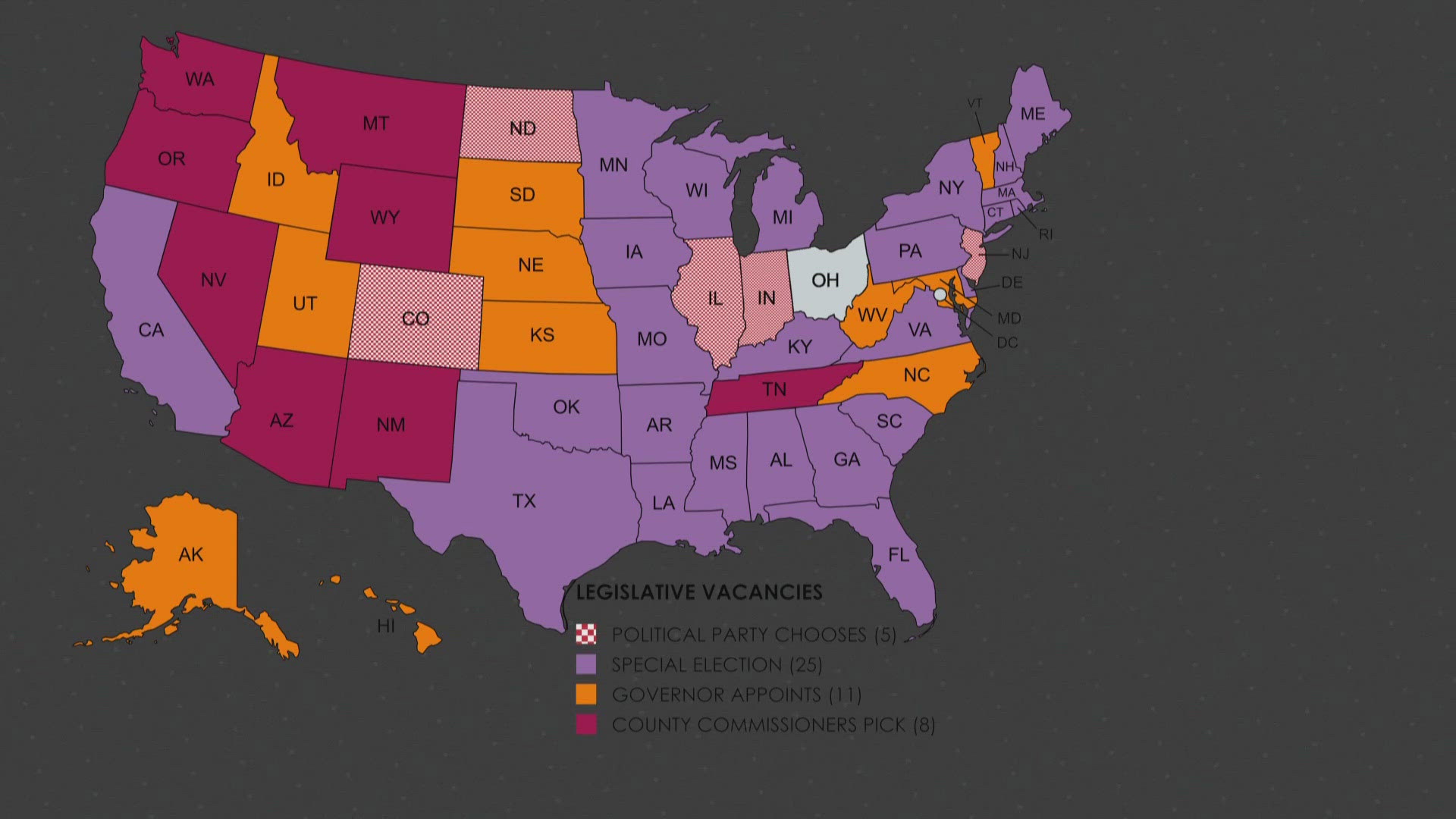

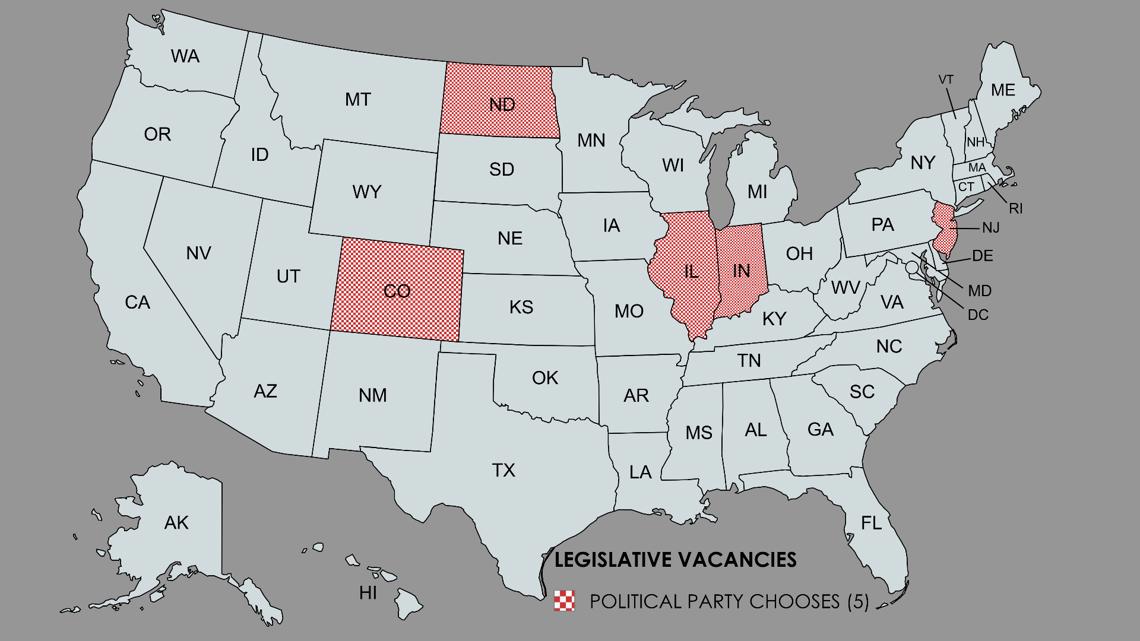

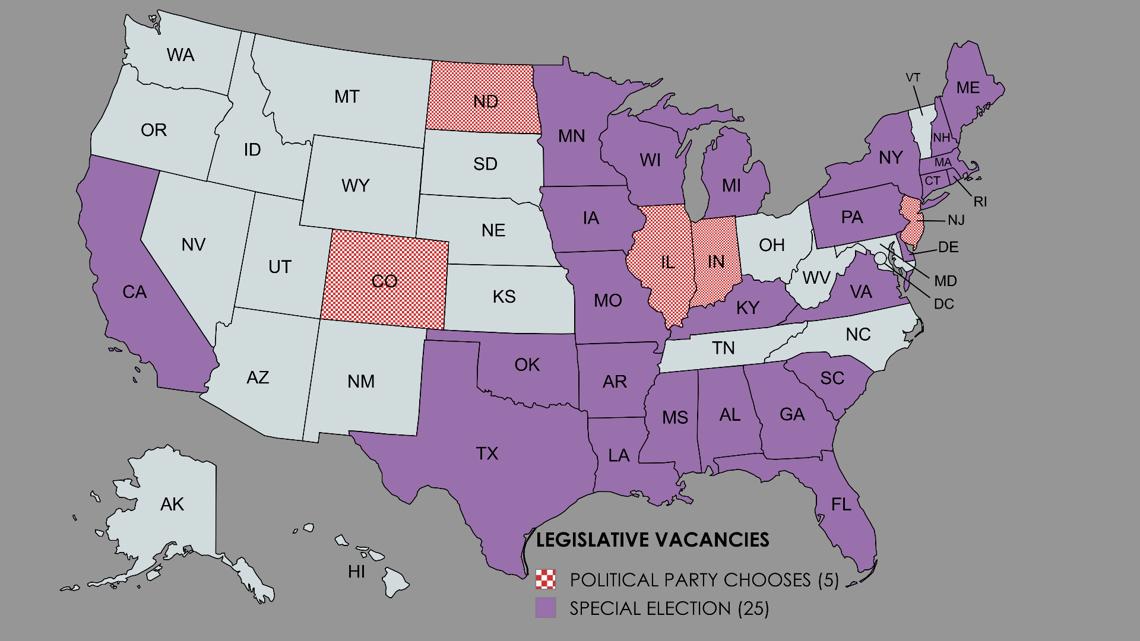

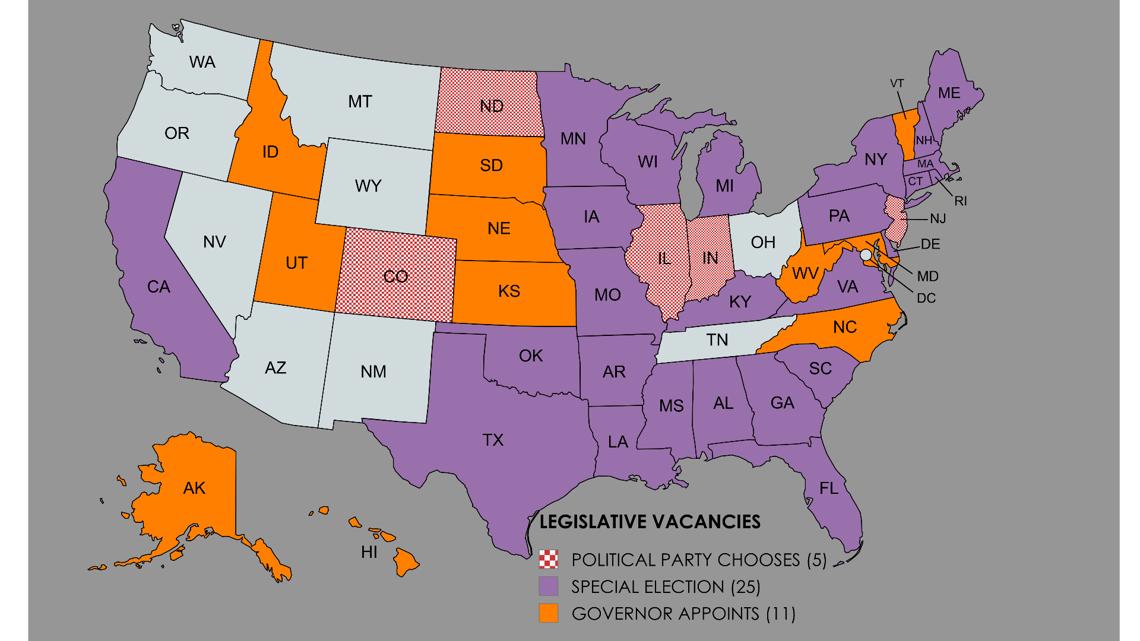

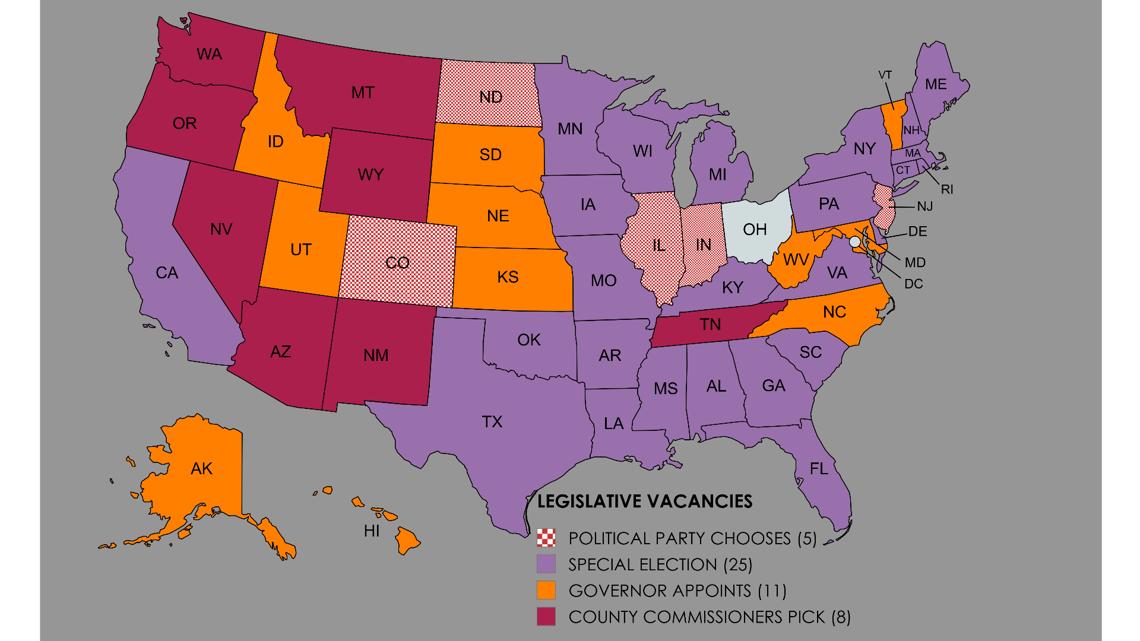

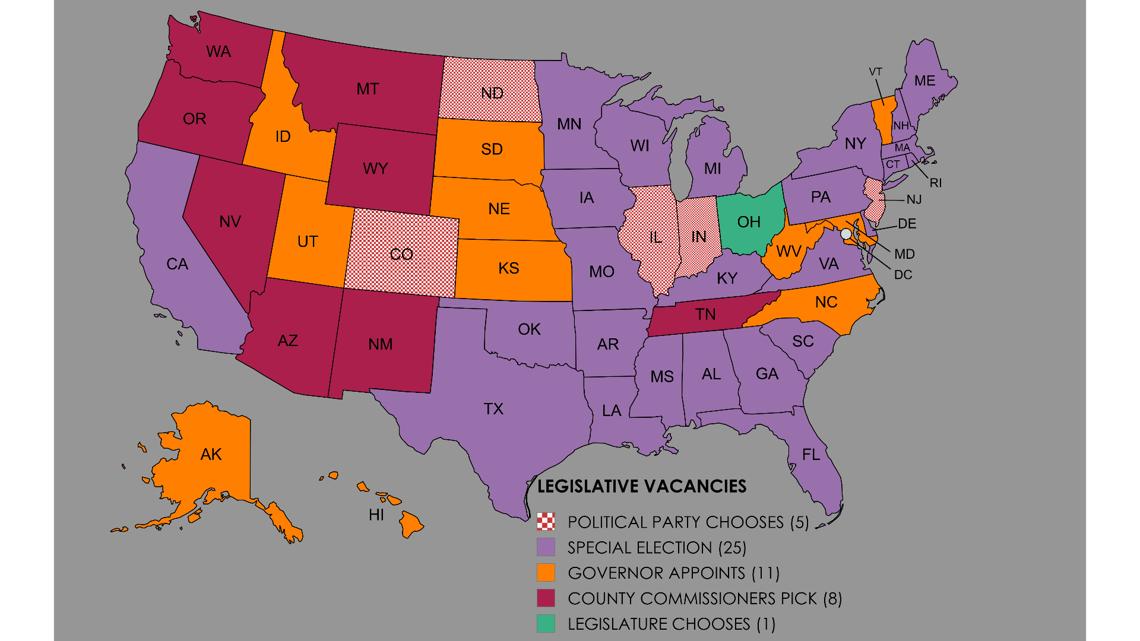

Colorado is just one of five states with that process, where a vacancy committee is convened among party leaders in the vacant district’s territory.

Last week, Denver Democrats Chair James Reyes said that the vacancy committee for Hansen’s Senate District would be around 120 people. Hansen’s district covers Lowry, Cherry Creek, Cap Hill, Wash Park and downtown Denver.

North Dakota, Illinois, Indiana and New Jersey also use vacancy committees to fill state legislative vacancies.

“Let me start by saying there is no good way to do this,” State Sen. Jeff Bridges, D-Greenwood Village, said. “If there was an easy, clear, genuinely best way to do this, everyone would be doing it.”

Bridges went from the State House to the State Senate in 2019 when he got the majority of votes from a vacancy committee of 118 Democrats. Bridges was chosen to fill the seat left vacant with the resignation of then-State Sen. Daniel Kagan.

“When my state Senate spot opened up, I ran for that vacancy committee. That's the hardest election I have ever run in my life,” Bridges said. “It was sitting in people's living rooms, having extensive one-on-one conversations with them and building to the vote that I got in that was, genuinely, the hardest election that I have ever run.”

SPECIAL ELECTIONS

In 25 states, including California, Texas, Florida and New York, a special election fills a state legislative vacancy.

The positive of that would be that the entire district gets to pick.

The negatives include the cost of a special election and the time needed to get it conducted.

“That they cost a little bit more money should never be why we don't choose a particular way of electing our representatives,” Bridges said. “I think, 90 days minimum, we would need to just set up and have a special election for something like this. That's 90 days during a 120-day session that that district doesn't have representation.”

He also believes a special election favors a wealthy or well-known candidate.

“The challenge with the snap election model is, not only that you would have a lack of representation for the people in that district during the period of time that the election is running, it's also that the person most likely to win an extraordinarily short election like that is the person with the most money or the person who is already the most well-known,” Bridges said.

GOVERNOR APPOINTEE

In 11 states, many of which surround Colorado, the governor appoints the state legislative replacement.

Of the 11, only Alaska, Hawaii, Idaho and Maryland require the governor to appoint someone of the same party as the lawmaker who vacated the seat.

The positive of that is a swift replacement.

The negative is that it is one person making the decision, and they could be a different party than the lawmaker voters put in office.

“Do you really want the governor appointing?” Bridges asked. “If the legislature is deciding what the new process would be, that we would put that power in the hands of the governor is unlikely.”

COUNTY COMMISSIONER APPOINTEES

In eight states, mainly in the mountain areas and west, county commissioners pick the replacement. Only Arizona, Nevada and Oregon require the replacement to be from the same party as the lawmaker who left.

A big negative would be that many legislative districts cover many counties, so there would be a difference of opinion and, likely, a need for a weighted system based on how much each county is represented by that seat.

“Neither Senate nor House districts align with county lines,” Bridges said. “And then, you have Senate districts that consist of like a dozen counties.”

LEGISLATURE DECIDES

Ohio is alone with its method. That state replaces state legislative vacancies by having the decision made by the chamber and party of the lawmaker leaving. For example, if a Senate Democrat left office, the remaining Senate Democrats would choose the replacement.

Bridges said he once recommended having the Senate or House leadership decide.

“How about we have the head of the party in whichever chamber the person is leaving, choose who the next person will be. They hated that idea. Nobody liked that idea,” Bridges said.

The consensus among states is that there is no consensus.

“The fact that you have a map with that many colors on it that's that variable shows there's no best way of doing this,” Bridges said. “Every option has drawbacks. Every option has benefits.”

Earlier this year, State Rep. Bob Marshall, D-Highlands Ranch, introduced a bill to ban the vacancy selection from running in that district’s next election.

For example, whoever is appointed to Hansen’s seat will serve until 2026, when that district will hold a special election for the remaining two years of the four-year term. Marshall’s bill would have prevented the vacancy pick from running for that seat in 2026.

That bill passed one committee before dying.

“There's no best way to do this,” Bridges said. “I am not wholly convinced that the way we do it now is the right way. I'm not wholly convinced that that some other way would be better.”