And you thought finding a parking place could be difficult.

To reach its reserved spot on Mars, NASA’s InSight lander on Monday must hit a precise spot in the Red Planet’s upper atmosphere, survive a searing plunge to the surface involving a supersonic parachute and touch down softly on a tripod of legs.

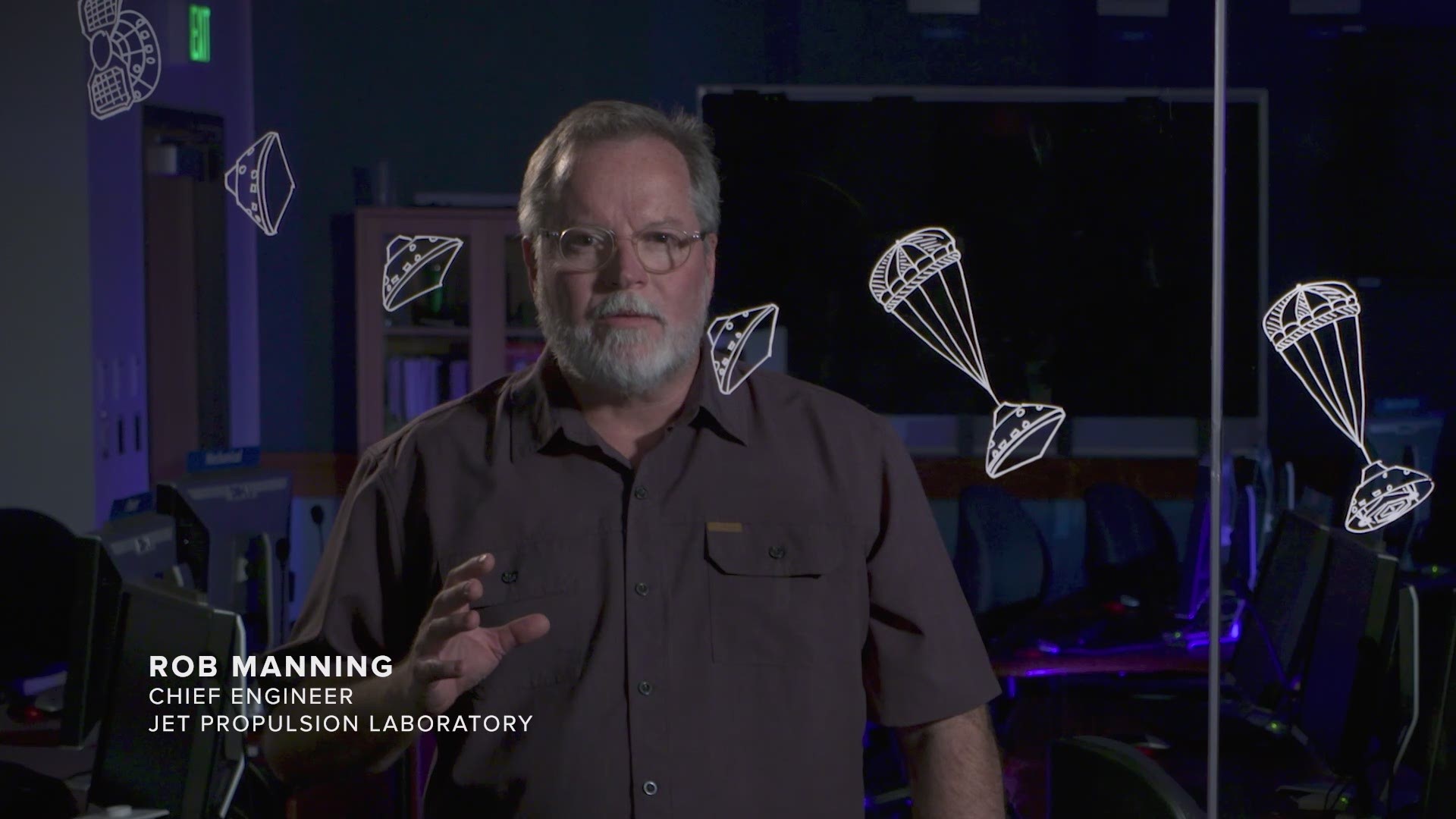

Mission managers at the space agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California are feeling a mix of excitement and nerves about the process formally called Entry, Descent and Landing, or EDL, but informally known as “seven minutes of terror.”

“Everything that we’ve done to date makes us feel comfortable and confident we’re going to land on Mars,” said Tom Hoffman, the mission’s project manager at JPL. “But everything has to go perfectly, and Mars could always throw us a curveball.”

Less than half of the missions ever launched to Mars have made it to their destination.

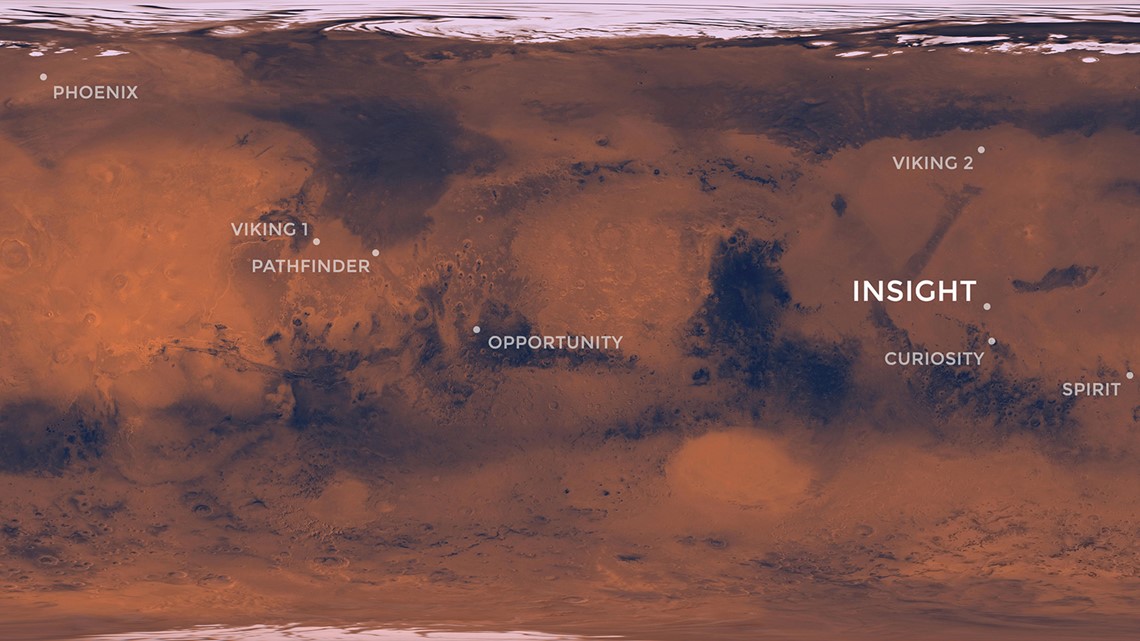

NASA’s $814 million InSight mission, which plans to study Mars’ deep interior, will take its turn six years after the Curiosity rover and nearly seven months after a May 5 blastoff from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California on an Atlas V rocket.

Around 2:40 p.m. EST Monday, the probe will pivot its heat shield to face Mars and separate from a cruise stage that on Sunday briefly fired an engine one last time — equivalent to a “breath of air,” Hoffman said — to line up the landing zone.

The target: Elysium Planitia, or a “heavenly plain” near Mars’ equator that Hoffman hopes offers “a really flat-looking area, much like a giant Walmart parking lot.”

Minutes later, the spacecraft will hit the upper atmosphere at 12,300 mph, needing to slow down to 5 mph, or else risk creating a new crater on the Martian surface.

Landing on Mars is a particularly difficult challenge, NASA says, because its gravitational pull combined with a very thin atmosphere, about 1 percent of Earth’s, makes slowing down hard.

InSight’s heat shield will feel temperatures approaching 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit — hot enough to melt steel — during its descent.

If all goes well, after slowing to about 850 mph, at roughly seven miles above the surface, the spacecraft will pop out a supersonic parachute for more braking power, then drop its heat shield, deploy three landing legs and begin scanning the surface with radar pulses.

After shedding a backshell and a brief free-fall, InSight will fire a dozen retro-rockets to soften the 789-pound lander’s touchdown in a cloud of red dust around 2:47 p.m.

Back on Earth, white-knuckled engineers at JPL will await word of the lander’s fate.

Within about eight minutes, the time radio signals will take to traverse the 91 million miles to Earth, they hope to hear a beep signifying that the lander is safe.

“I’m going to be very excited once we get that first signal back that shows we’ve successfully landed on Mars,” said Hoffman.

Teams may get more information from a pair of tiny “stalkers” that launched with the lander.

Two experimental NASA spacecraft known as CubeSats, each about the size of a briefcase, are the first of their kind to travel in deep space. Engineers hope they'll be able to relay news about the lander’s descent and health as they fly by the Red Planet roughly 3,000 miles behind InSight.

Otherwise, mission teams will have to be patient. NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter will fly overhead and transmit the data about three hours after landing. Confirmation that power-generating solar arrays have unfurled will take closer to six hours.

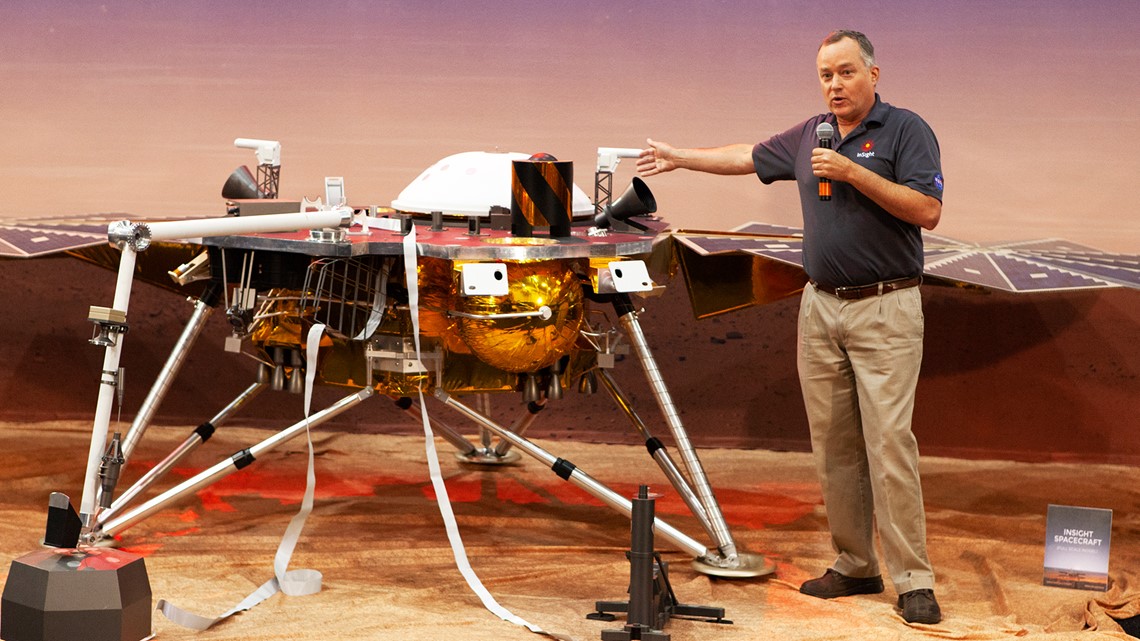

InSIght — short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport — then will begin a months-long process of robotically placing science several instruments on the surface of Mars, chief among them a seismometer provided by France.

That will begin a minimum two-year study of the layers making up the planet’s, crust, mantle and core, measuring “marsquakes” to create a 3-D picture of Mars’ interior.

Scientists expect that knowledge to advance understanding about the evolution of planets, including Earth and planets orbiting other stars.

“There’s a lot of things that can go wrong,” Bruce Banerdt, the mission’s lead scientist from JPL, said Sunday. “I’m actually really confident, personally, that we’re going to land safely (Monday). Doesn’t mean I’m not nervous.”