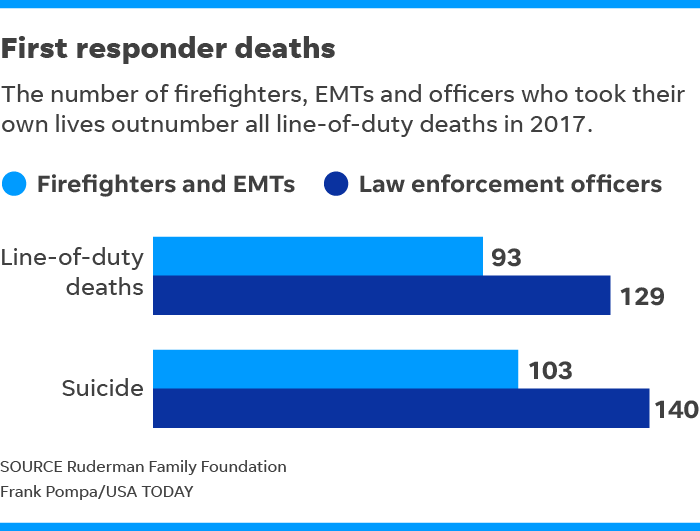

Suicides left more officers and firefighters dead last year than all line-of-duty deaths combined — a jarring statistic that continues to plague first responders but garners little attention.

A new study by the Ruderman Family Foundation, a philanthropic organization that works for the rights of people with disabilities, looked at depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and other issues affecting first responders and the rates of suicide in departments nationwide.

The group found that while suicide has been an ingrained issue for years, very little has been done to address it even though first responders have PTSD and depression at a level five times that of civilians.

Last year, 103 firefighters and 140 police officers committed suicide, whereas 93 firefighters and 129 officers died in the line of duty, which includes everything from being fatally shot, stabbed, drowning or dying in a car accident while on the job.

Miriam Heyman, one of the co-authors of the study, said the numbers of suicide are extremely under-reported, while other more high-profile deaths make headlines. There were 46 officers who died after being fatally shot on the job in 2017, nearly 67% less than the number of suicides.

The number of firefighter suicides may only represent about 40% of the deaths, she said, meaning the deaths could total more than 250 — more than double the amount of all line-of-duty deaths.

“It’s really shocking, and part of what’s interesting is that line-of-duty deaths are covered so widely by the press but suicides are not, and it’s because of the level of secrecy around these deaths, which really shows the stigmas,” Heyman said.

She said departments don’t release information about suicides, and less than 5% have suicide-prevention programs. It’s something first responders are ashamed to talk about and address, which is having a deadly result, she said.

“There is not enough conversation about mental health within police and fire departments,” the study says. “Silence can be deadly, because it is interpreted as a lack of acceptance and thus morphs into a barrier that prevents first responders from accessing potentially life-saving mental health services.”

The stigma isn’t just in silence, the study outlines. Families want to hide the reasoning behind the death of a loved one. Officers feel they’ll be looked down on or taken off the job if they speak up about depression. Dying by suicide means they aren’t buried with honor.

There have been some discussions and pushes for mental health programs in departments, but the process is slow.

The report highlights programs and policies to push the issue, such as peer-to-peer assistance, mental health check-ups, time off after responding to a critical incident and family training programs to identify the warning signs of depression and PTSD.

A project published this year by the International Association of Chiefs of Police detailed the issues around suicide and highlighted many of the same programs. It noted that first responder suicide is nearly impossible to track since it's often not reported.

"It is a departmental issue that should be addressed globally," the report notes. "Departments must break the silence on law enforcement suicides by building up effective and continuing suicide-prevention programs."

A big push is for police and fire chiefs to address depression and suicide more candidly and share their experiences.

Attention is sometimes given to PTSD in the immediate aftermath of a high-profile incident, such as a natural disaster, terror attack or mass shooting, like the recent high school shooting in Parkland, Fla.

“Here’s the reality, though: Police and firefighters witness death and destruction daily,” Heyman said. “It would be silly to think it wouldn’t put a toll on them.”

She said when first responders are affected and don’t get help, it can also have a negative result on the community they serve and can be thought of more as an “occupational hazard.”

“These individuals are the guardians for our community,” Heyman said. “What happens when their decision-making is flawed? We need for them to be healthy.”

Follow Christal Hayes on Twitter: @Journo_Christal