WASHINGTON — U.S. health regulators on Thursday approved new prescribing instructions that are likely to limit use of a controversial new Alzheimer’s drug.

The Food and Drug Administration said the change is intended to address confusion among physicians and patients about who should get the drug, which has faced an intense public backlash since its approval last month.

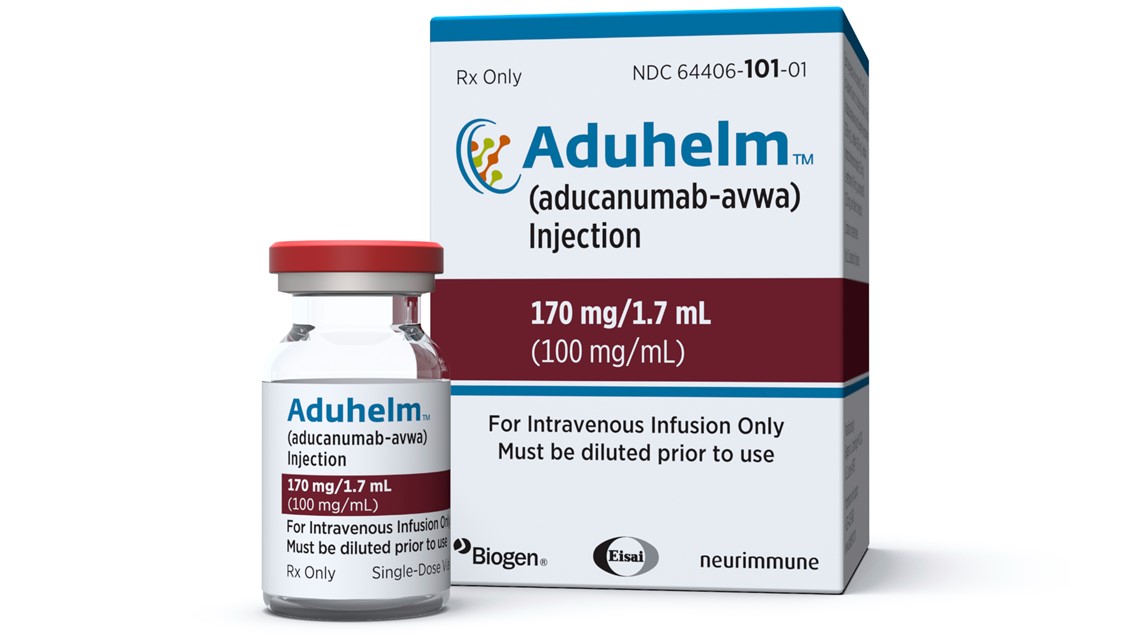

The new drug label emphasizes that the drug, Aduhelm, is appropriate for patients with early or mild Alzheimer's but has not been studied in patients with more advanced disease. That's a big change from the original FDA instructions, which said simply that the drug was approved for Alzheimer's disease in general.

Drugmaker Biogen announced the change in a release Thursday, stating that the update is intended to “clarify” the patients studied in the company trials that led to approval. The FDA first approached the company about narrowing the label and approved the language.

“Hearing these concerns, FDA determined that clarifications could be made to the prescribing information to address this confusion,” the agency said in an emailed statement. Despite the update, the FDA added that “some patients may benefit from ongoing treatment” if they develop more advanced Alzheimer’s.

When the drug was first approved a top FDA official told reporters the drug was “relevant to all stages of Alzheimer’s disease.”

The label change comes one month after FDA’s approval of the drug, which quickly sparked controversy over its $56,000-a-year price-tag and questionable benefits. Three of FDA’s outside advisers resigned over the decision with one prominent Harvard expert calling it the “worst drug approval decision in recent U.S. history.”

Such sweeping changes to drug labels are rare, particularly only a few weeks after approval.

Aduhelm hasn't been shown to reverse or significantly slow the disease. But the FDA said that its ability to reduce clumps of plaque in the brain is likely to slow dementia. Many experts say there is little evidence to support that claim.

Biogen is required to conduct a follow-up study to definitively answer whether the drug slows mental decline. Other Alzheimer's drugs only temporarily ease symptoms.

Because of its price and broad approval some analysts have worried that Aduhelm could add tens of billions in new expenses to the U.S. health care system, particularly the federal government's Medicare program. Alzheimer’s affects about 6 million Americans, the vast majority old enough to qualify for Medicare.

Two congressional committees in the House have launched an investigation into the FDA's review of the drug. And lawmakers in the Senate have called for hearings into the drug’s cost and impact on federal spending.

The narrower label may ease some of those concerns by shrinking the number of patients likely to get the drug, which requires monthly IVs. Many hospitals have already stated that they plan to limit the drug's use to patients with earlier stage disease. Doctors could still prescribe the drug for more advanced patients, though insurers might refuse to pay for it, citing the FDA label.

“It was pretty troubling that the previous label was so broad and included groups of patients in whom the drug had never been tested,” said Dr. Suzanne Schindler of Washington University in St. Louis. “I think this is a positive change because it better reflects the patients in whom the drug was actually studied.”