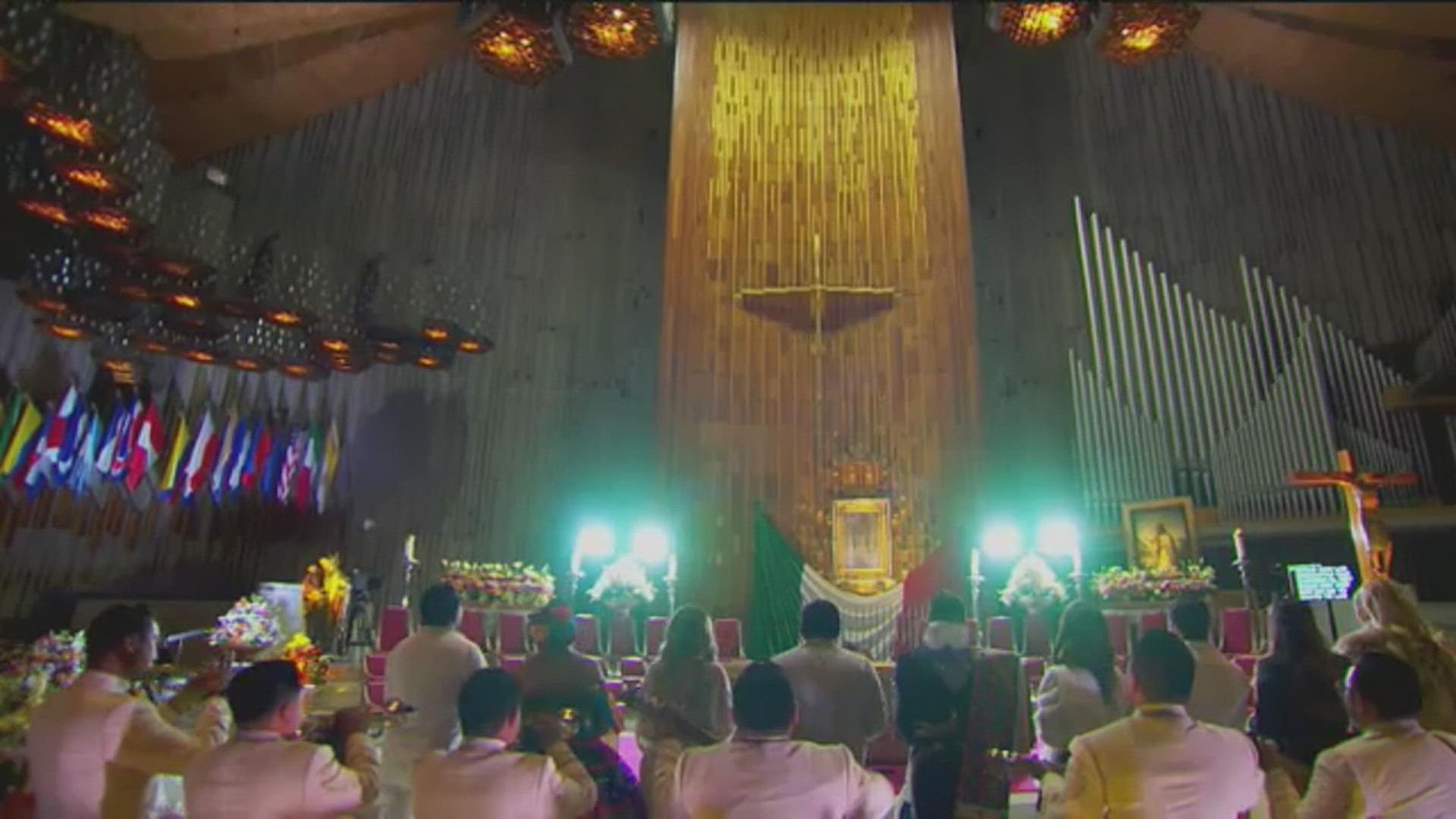

It is one of the world’s most visited and beloved religious venues – the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, with a circular, tent-shaped roof visible from miles away and a sacred history that each year draws millions of pilgrims from near and far to its hilltop site in Mexico City.

Early December is the busiest time, as pilgrims converge ahead of Dec. 12, the feast day honoring Our Lady of Guadalupe. To Catholic believers, the date is the anniversary of one of several apparitions of the Virgin Mary witnessed by an Indigenous Mexican man named Juan Diego in 1531.

The COVID-19 pandemic curtailed the number of pilgrims in 2020. Last year, even with some restrictions still in place, attendance for the December celebrations rose to at least 3.5 million, according to local officials. Bigger numbers are expected this year.

For many pilgrims, their journey to the site is an expression of gratitude for miracles that they believe the Virgin brought into their lives. Around the basilica, some people light candles while praying in silence. Some kneel and weep. Others carry statues of the Virgin in their arms as they receive a priest’s blessing.

Among the first-time pilgrims this year was Yamilleth Fuente, who entered the basilica wearing a yellow scarf decorated with an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

Fuente, who traveled alone to Mexico City from her home in El Salvador, said that she was diagnosed with cancer in 2014 and recovered after praying to the Virgin. When she suggested making the pilgrimage, her husband and two children encouraged her.

“I’ve loved the Virgin my whole life. I even used to dream about her,” Fuente said. “My daughter’s name is Alexandra Guadalupe because she’s also a miracle that the Virgin granted me."

For the Catholic Church, the image of the Virgin is a miracle itself – dating to a cold December dawn in 1531 when Juan Diego was walking near the Tepeyac Hill.

According to Catholic tradition, Juan Diego heard a female voice calling to him, climbed the hill and saw the Virgin Mary standing there, in a dress that shone like the sun. Speaking to him in his native language, Nahuatl, she asked for a temple to be built to honor her son, Jesus Christ.

As the church teaches, Juan Diego ran to notify the local bishop, who was skeptical, and then returned to the hill for more exchanges with the Virgin. At her suggestion, he left the hillside carrying flowers in his cloak, and when he later opened the cloak in the bishop’s presence it displayed a detailed, colorful image of the Virgin.

That piece of cloth currently hangs in the center of the Basilica, protected by a frame.

In an annotated edition of the apparition story, the Rev. Eduardo Chavez – a leading expert on the topic -- said the Virgin’s appearance occurred in a time of despair. By 1531, 10 years after the Spaniards’ conquest of the Aztecs, smallpox had killed nearly half of Mexico’s Indigenous population, wrecking their pre-conquest social and religious systems.

To many Mexicans, the Virgin’s image became a symbol of unity because her face looks mixed-race -- neither fully Indigenous nor European, but a bit of both.

Some academics have said that the devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe intertwines Indigenous and Catholic beliefs, though the Catholic Church rejects this theory. At the foot of the hill that today accommodates the basilica was a temple for the goddess Coatlicue Tonantzin, and the date of the apparition coincided with an Indigenous festival.

On a recent day, numerous motorcycle taxis were parked on one of the esplanades outside the basilica. Abraham García, a 45-year-old driver from the nearby city of Nezahualcóyotl, was there, accompanied by more than 70 colleagues.

“We come year after year to thank God, the basilica and the Virgin, and to ask her for help,” he said. “This was a good year for us, so now we’ll leave even more blessed.”

Many of the drivers’ vehicles have stickers bearing the Virgin’s image on their windows; others display a statuette of her under the rear-view mirror.

According to Nayeli Amezcua, a researcher at the National School of Anthropology and History, images and carvings play a substantial role in this faith.

“Catholicism is a very sensory religion... Through many objects, the sacred is transmitted,” she said. “We could think of them as representations, but for those who believe, the images themselves are alive.”

Fuente, the Salvadoran pilgrim, is eager to share the fervor of her faith.

“My entire life is filled with miracles from God and the Blessed Virgin,” she said. “You could write a book about all that she has done for me.”

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Hispanic Heritage