WASHINGTON — Union activist Terrance Wise recalls being laughed at when he began pushing for a national $15 per hour minimum wage almost a decade ago. Nearly a year into the pandemic, the idea isn't so funny.

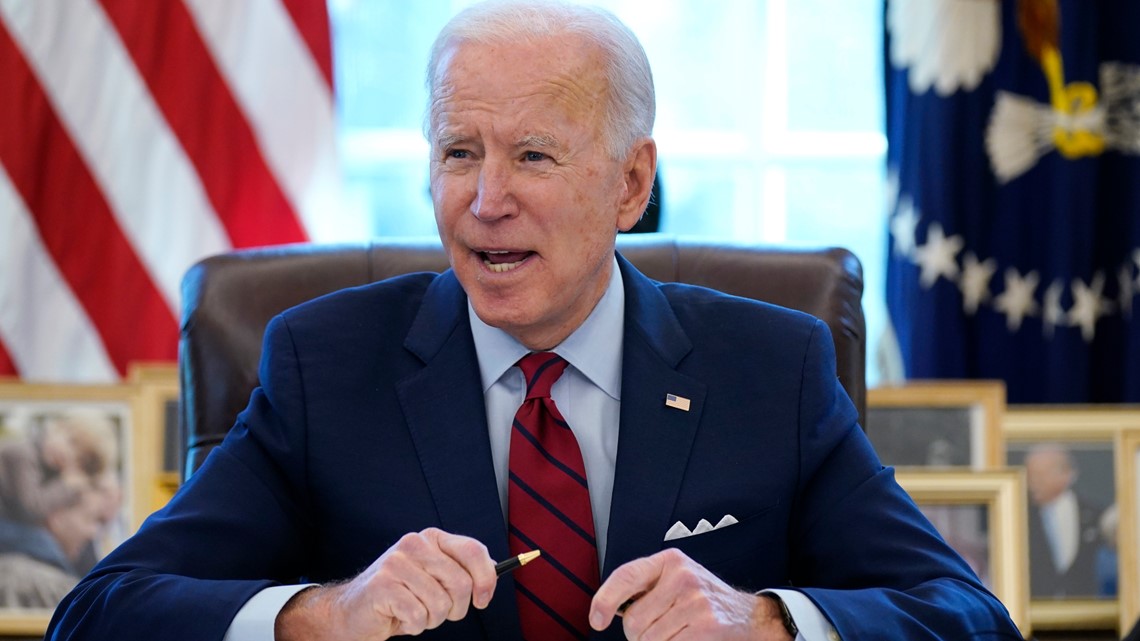

The coronavirus has renewed focus on challenges facing hourly employees who have continued working in grocery stores, gas stations and other in-person locations even as much of the workforce has shifted to virtual environments. President Joe Biden has responded by including a provision in the massive pandemic relief bill that would more than double the minimum wage from the current $7.25 to $15 per hour.

But the effort is facing an unexpected roadblock: Biden himself. The president has seemingly undermined the push to raise the minimum wage by acknowledging its dim prospects in Congress, where it faces political opposition and procedural hurdles.

That's frustrating to activists like Wise, who worry their victory is being snatched away at the last minute despite an administration that's otherwise an outspoken ally.

“To have it this close on the doorstep, they need to get it done,” said Wise, a 41-year-old department manager at a McDonald's in Kansas City and a national leader of Fight for 15, an organized labor movement. "They need to feel the pressure.”

The minimum wage debate highlights one of the central tensions emerging in the early days of Biden's presidency. He won the White House with pledges to respond to the pandemic with a barrage of liberal policy proposals. But as a 36-year veteran of the Senate, Biden is particularly attuned to the political dynamics on Capitol Hill and can be blunt in his assessments.

"I don’t think it's going to survive,” Biden recently told CBS News, referring to the minimum wage hike.

There's a certain political realism in Biden's remark.

With the Senate evenly divided, the proposal doesn't have the 60 votes needed to make it to the floor on its own. Democrats could use an arcane budgetary procedure that would attach the minimum wage to the pandemic response bill and allow it to pass with a simple majority vote.

But even that's not easy. Some moderate Democratic senators, including Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Krysten Sinema of Arizona, have expressed either outright opposition to the hike or said it shouldn't be included in the pandemic legislation.

The Senate's parliamentarian could further complicate things with a ruling that the minimum wage measure can't be included in the pandemic bill.

For now, the measure's most progressive Senate backers aren't openly pressuring Biden to step up his campaign for a higher minimum wage.

Bernie Sanders, the chair of the Senate Budget Committee, has said he's largely focused on winning approval from the parliamentarian to tack the provision onto the pandemic bill. Sen. Elizabeth Warren, who like Sanders challenged Biden from the left for the Democratic nomination, has only tweeted that Democrats should “right this wrong."

Some activists, however, are encouraging Biden to be more aggressive.

The Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II, the co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign, said Biden has a “mandate” to ensure the minimum wage increases, noting that minority Americans were “the first to go back to jobs, first to get infected, first to get sick, first to die” during the pandemic.

“We cannot be the last to get relief and the last to get treated and paid properly,” Barber said. “Respect us, protect us and pay us.”

The federal minimum wage hasn’t been raised since 2009, the longest stretch without an increase since its creation in 1938. When adjusted for inflation, the purchasing power of the current $7.25 wage has declined more than a dollar in the last 11-plus years.

Democrats have long promised an increase — support for a $15 minimum wage was including in the party’s 2016 political platform — but haven’t delivered.

Supporters say the coronavirus has made a higher minimum wage all the more urgent since workers earning it are disproportionately people of color. The liberal Economic Policy Institute found that more than 19% of Hispanic workers and more than 14% of Black workers earned hourly wages that kept them below federal poverty guidelines in 2017.

Blacks, Hispanics and Native Americans in the U.S. also have rates of hospitalization and death from COVID-19 that are two to four times higher than for whites, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

People of color are a vital part Biden’s constituency, constituting 38% of his support in November’s election, according to AP VoteCast, a nationwide survey of the electorate.

The White House says Biden isn’t giving up on the issue. His comments to CBS, according to an aide, reflected his own evaluation of where the parliamentarian would rule based on his decades of experience in the Senate dealing with similar negotiations.

Biden suggested in the CBS interview that he’s prepared to engage in a “separate negotiation” on raising the minimum wage, but White House press secretary Jen Psaki offered no further details on the future of the proposal if it is in fact cut from the final coronavirus aid bill.

One option could be forcing passage by having Vice President Kamala Harris, as the Senate’s presiding officer, overrule the parliamentarian. But Psaki was clear in opposing that: “Our view is that the parliamentarian is who is chosen, typically, to make a decision in a nonpartisan manner.”

Navin Nayak, executive director of the Center for American Progress Action Fund, the political arm of the progressive think tank, said he wasn’t surprised at Biden’s assessment, but still feels the White House is making good faith efforts.

Nayak’s and other progressive groups, like MoveOn, have worked closely with the Biden team throughout its transition to the White House to ensure their priorities made it into the COVID relief bill — and were mollified by the inclusion of the $15 an hour minimum wage increase, the temporary expansion of the child tax credit and rental assistance.

“They’re not putting this in there to lose it — they put it in there to win it,” Nayak said.

Nayak also noted Biden’s comments came before a Congressional Budget Office projection that found the proposal would help lift millions of Americans out of poverty but increase the federal deficit and cost 1.4 million jobs as employers scale back costlier workforces.

Sanders and other supporters haven't been as pessimistic about their legislative chances as the president, insisting that they can make the minimum wage increase work as part of COVID relief and refusing to discuss an alternative. They argue that the CBO finding that raising the minimum wage will increase the deficit means it impacts the budget — and should therefore be allowed. But that will ultimately be up to the Senate parliamentarian.

For Wise, potential congressional hurdles pale in comparison to real world realities.

He makes $14 an hour and his fiancé works as a home health care professional. But when she went into quarantine because of possible exposure to the coronavirus and he missed work to care for their three daughters, it wasn’t long before the family was served with an eviction notice.

People “figure it’s something we’re doing wrong. We’re going to work. We’re productive. We’re law-abiding citizens,” Wise said. “It shouldn’t have to be that way.”

___

Associated Press writers Alan Fram and Kevin Freking contributed.