![636028205455499426-9780812993349.jpg [image : 86532244]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/media/2016/06/29/USATODAY/USATODAY/636028205455499426-9780812993349.jpg)

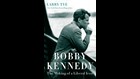

The endless churn of books about the Kennedy clan can leave readers weary in advance whenever another one, inevitably, pops up. But Larry Tye’s new biography, Bobby Kennedy: The Making of a Liberal Icon (Random House, 608 pp., *** out of four stars) is proof enough that America’s fabled family hasn’t exhausted its narrative momentum.

Looking back at it in literary terms, Robert F. Kennedy’s martyrdom on June 5, 1968, at age 42, seems almost overdetermined. It followed on the heels of Martin Luther King’s assassination two months earlier, and five years after his older brother, President John F. Kennedy, fell in Dallas.

RFK’s end came with a spray of bullets at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. He had just captured California’s Democratic presidential primary amid a steamrolling, inspirational bid for the presidency, in support of civil rights and in opposition to the Vietnam War. By then, the decade’s toll of tragedies had taken on an inexorable rhythm.

![636028206658267136-tye-author-photo-no-credit-needed.jpg [image : 86532330]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/media/2016/06/29/USATODAY/USATODAY/636028206658267136-tye-author-photo-no-credit-needed.jpg)

Author Tye, a lauded Boston-based journalist, captures RFK’s rise and fall with straightforward prose bolstered by impressive research. Along with hundreds of interviews with Kennedy intimates, including his widow, Ethel, Tye sifted through unpublished memoirs, unreleased government files, and boxes of Kennedy papers that had been locked away for some 40 years.

But, as often happens, such sweeping access doesn’t really answer the lingering tabloid questions: Did Bobby have extramarital affairs with Marilyn Monroe or Jacqueline Kennedy? More importantly, Tye defines RFKs’ evolution, from a cold-war minion of Sen. Joe McCarthy in the 1950s to the beacon of liberalism he became.

“The truth is that the early Bobby Kennedy embraced the overheated anticommunism of the 1950s and openly disdained liberals,” writes Tye. “His job with the Republican senator from Wisconsin not only launched Bobby’s career but injected into his life passion and direction that had been glaringly absent.”

![XXX BOBBY KENNEDY1356.JPG NON PEO GBR [image : 86532454]](http://www.gannett-cdn.com/media/2016/06/29/USATODAY/USATODAY/636028208201273027-AXX-EK.-cover-bobby.jpg)

If that seems an ironic leap for Tye to make — tracing Kennedy’s ultimate empathy to his initial role as a witch-hunting tribune of McCarthyism — it’s plausible enough. As his brother’s attorney general, RFK targeted foes, such as corrupt labor czar Jimmy Hoffa, with fanatical zeal. But in the wake of JFK’s assassination, we’re told, “Bobby continued as attorney general, but he found it difficult to reconnect with most of his old passions … The one issue that mattered enough to pull him out of his mist even temporarily was civil rights.”

Tragic as it is, Tye’s is a tale, inevitably, of white privilege on a rising tide of idealism, and there’s a hagiographic tilt to this latest portrait of Bobby. It hardly discredits the carefully attributed storytelling, but the familiar details — the plutocratic father, the golden older brothers, the sprawling, overachieving Catholic family — have long since congealed into the myth of an American Camelot, a favorite cliché.

Plumbing unpublished archives for fresh details doesn’t lead to revelation, reassessment, or new insight on liberalism. Instead, it affirms that most leaders are products of their time and temperament.