Colorado has received a lot of attention recently as one of the first states to allow recreational marijuana, but it’s also legalizing other things. Denver, one of the nation’s hottest urban real estate markets, is surrounded by municipalities that allow backyard chicken flocks.

This isn’t just happening in Colorado. Backyard chickens are cropping up everywhere. Nearly 1 percent of all U.S. households surveyed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture reported owning backyard fowl in 2013, and 4 percent more planned to start in the next five years. That’s over 13 million Americans flocking to the backyard poultry scene. Ownership is spread evenly between rural, urban and suburban households and is similar across racial and ethnic groups. A 2015 review of 150 of the most-populated U.S. cities found that nearly all (93 percent) allowed backyard poultry flocks.

Our lab group analyzes health issues that connect humans, animals and the environment. In a recent study with University of California, Davis animal scientist Joy Mench, we examined urban poultry regulations in Colorado – the only state that collects and makes public animal shelter surrender data. Our findings suggest that as backyard chicken farming spreads, states need to develop regulations to better protect animal welfare and human health.

When animals roamed the streets

U.S. cities once were powered by animals. Horses provided transport through the early 1900s. Pigs and hens fed on household garbage before municipal trash collection became routine. Thousands of cattle were driven up Fifth Avenue in New York City daily in the late 19th century, occasionally trampling children and pedestrians.

To reduce accidents, disease and nuisances, such as piles of smelly manure and dead animals, early public health and planning agencies wrote the first ordinances banning urban livestock. By the 1920s, farm animals and related facilities such as dairies, piggeries and slaughterhouses were barred from most U.S. cities. Exceptions were made during World War I and World War II, when meat was rationed, encouraging city dwellers to raise backyard birds.

Locavores and animal lovers

The local food movement has helped drive interest in raising backyard birds. People want to grow their own food. In response, cities across the country are modifying regulations and overturning long-standing bans to legally accommodate backyard chickens.

Surveys show that backyard chicken owners are concerned about where their food comes from, how it was produced and possible risks associated with eating industrially produced meat and eggs. They believe their birds have a better quality of life and produce safer and more nutritious eggs and meat than commercially raised versions.

Risks to humans and chickens

However, raising backyard chickens is not risk-free. As one example, an outbreak of highly infectious H5N1 avian influenza in Egypt resulted in 183 confirmed cases and 56 deaths between 2014 and 2016. The majority of clinically confirmed cases were linked to close contact with diseased backyard birds.

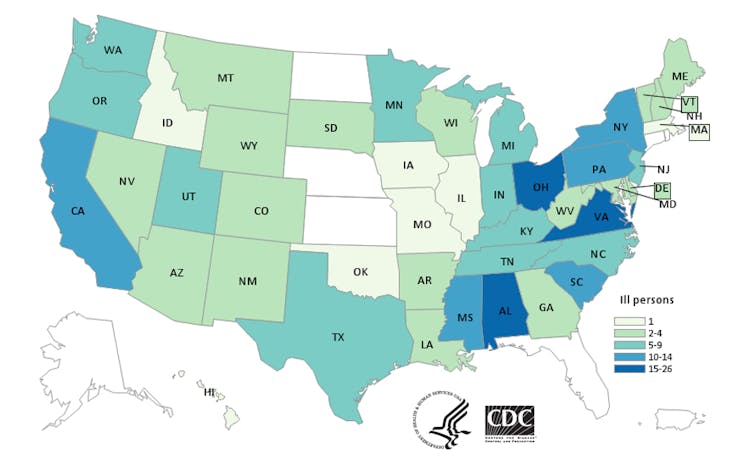

In the United States, contact with backyard poultry is associated with hundreds of multistate salmonella outbreaks every year. A 2016 USDA survey of backyard poultry owners found that 25 percent of respondents did not wash their hands after handling birds or eggs. In another study, the majority of backyard owners knew little about identifying or preventing poultry diseases.

Commercial poultry facilities protect birds against a variety of diseases by injecting vaccines into growing chicks while they are still in the egg. Many backyard growers do not know to request vaccinated birds when they purchase chicks or eggs. In 2002 an outbreak of exotic Newcastle disease in California originated in backyard flocks and spread into commercial poultry operations. Operators had to euthanize more than 3 million birds. They received compensation from USDA for doing so, which cost taxpayers US$161 million. USDA also had to restrict poultry exports, which caused economic losses for commercial poultry producers.

Many animal control and welfare agencies around the country oppose allowing urban livestock. Some activists argue that it can foster abuse, inhumane conditions and the development of backyard “factory farms,” and increase burdens on thinly stretched animal shelters and rescue groups.

Few rules for backyard flocks

We began our study by reviewing every local law in the state of Colorado pertaining to livestock. Then we looked at Colorado animal shelter and rescue data for 2014 and 2015. We wanted to see whether counties with large commercial operations were likely to prohibit raising backyard birds; when most ordinances originated; and what animal care standards were written into local laws.

We found that 61 of 78 Colorado municipalities allowed backyard chickens, and only 13 municipalities explicitly banned the practice. Local laws most commonly controlled for coop design and placement, prohibited owning roosters and limited the total number of birds allowed. Unlike commercial guidelines or typical standards for domestic cats and dogs, most ordinances did not require vaccination or veterinary care.

Very few regulations required humane slaughter or disease reporting. Only four municipalities required owners to provide birds with food; 16 required water, and two mandated veterinary care as warranted. Many owners understand that water and food are basic necessities, but when cities do not codify these requirements, animals have little legal protection and are not officially entitled to veterinary care even when they are sick, injured or dying.

On the positive side, we found that most shelters had not yet experienced an increase in chicken intake, and reported that people were interested in taking in stray chickens. But several organizations were concerned that they would receive more chickens in the future as the number of homes with space for stray birds decreased.

Setting higher standards

We found several cities with model ordinances that safeguarded avian and human health. Fort Collins, home to Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, requires annual permitting fees that are collected by the nonprofit Larimer Humane Society. The agency educates owners about disease prevention and husbandry and connects them with veterinarians and agricultural extension agents.

Nonprofit animal welfare agencies often depend heavily on donations to run animal shelters and care for strays. Fee systems such as that required in Fort Collins can help them cover costs of managing unwanted and stray animals. And streamlined permitting overseen by animal welfare agencies and veterinarians can prevent many backyard diseases or catch them early.

![]() Based on our survey of Colorado, we believe cities need to carefully consider their backyard chicken regulations and develop strong legal frameworks that protect animal and human health and welfare. In particular, they should develop rules that require food and water, mandate veterinary care and connect owners with animal welfare agencies.

Based on our survey of Colorado, we believe cities need to carefully consider their backyard chicken regulations and develop strong legal frameworks that protect animal and human health and welfare. In particular, they should develop rules that require food and water, mandate veterinary care and connect owners with animal welfare agencies.

Catherine Brinkley, Assistant Professor of Community and Regional Development, University of California, Davis and Jacqueline Kingsley, Master's Degree Candidate in Community Development, University of California, Davis

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.