DENVER — Numbers don’t represent people. But when you look at the numbers there’s an alarming trend showing a rise in violence among teens. Those working to prevent it are humans who say they are burnt out.

"The last year has been rough for me. It’s almost made me hate this job because it’s so much violence," said UCHealth Outreach Worker, Lawrence Goshon. "It’s not just teens. It's adults.”

Goshon said one of his worst nights in 2022 was when he got a trauma activation from the Emergency Department at the University of Colorado Hospital. He often responds to the calls that involve teens and gun violence.

“The young kid came in shot up. He was 14 years old,” he said.

It’s a troubling experience for Goshon but also for Dr. Catherine Velopulos, a trauma surgeon at UCHealth. Both often work together with the hopes of saving lives.

"That was a very hard experience. That one was very hard for me because I felt like I'm not making a difference,” Velopulos said.

Both say there was no real reason behind the shooting.

These young victims are the ones that trouble them and others that work in youth violence prevention.

"A gun in the hands of a 14-year-old brain is a scary thing," said Patrick Hedrick, the Director of Denver Public Safety Youth programs. "There's impulsivity there and the brain's not developed."

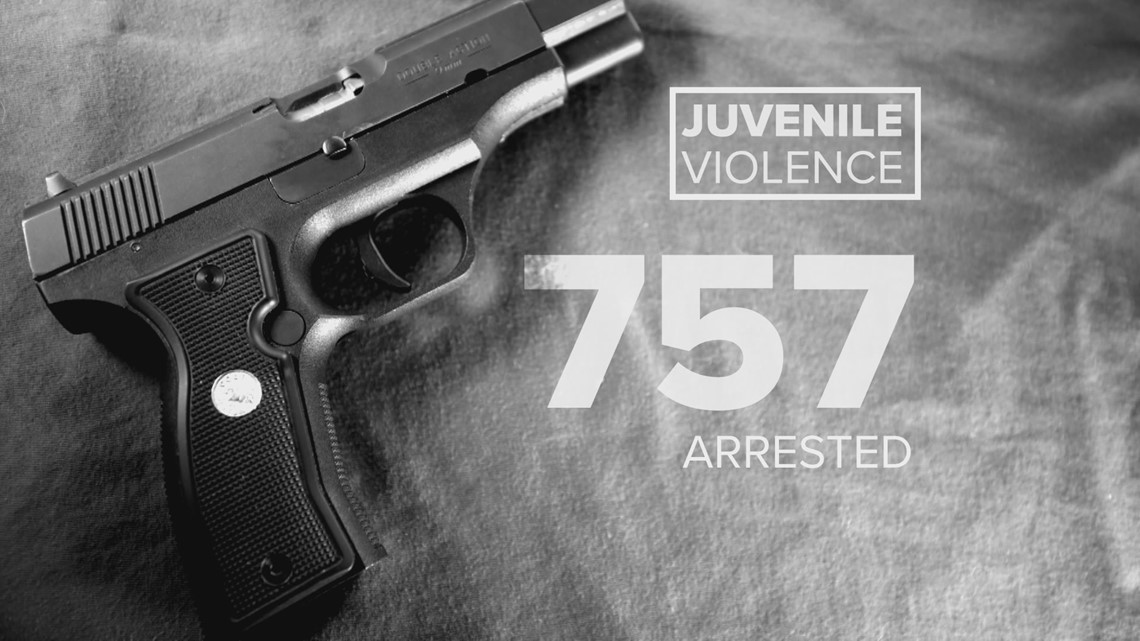

According to the Colorado Bureau of Investigation (CBI), in 2022 throughout the city of Denver, 979 kids between the ages of 10 and 17 were victims of violent crimes. There were 757 arrested for violent crimes in Denver. Crimes like assault, robbery, and even murder.

"I think our arrest numbers will show that things are trending up a little bit,” Hedrick said.

That’s about a 20 % increase throughout the city. On the state level 13%.

"Kids charged with murder, attempted murder, has increased. Handgun possession charges is probably the top charge now that we see," Hedrick said. "But unfortunately, murder charges are filed against juveniles from time to time."

For the last 22 years, Hedrick has worked for the City and County of Denver as the Director of Public Safety Youth Programs. He believes there needs to be more options for teens committing these crimes.

"We might be expecting this young person to completely change their behavior, but we're putting them right back in the same situation,” he said.

So instead of putting a kid back in the same situation with expectations of different results, they go a step further to determine what support is needed.

"How can we get those supports and services in place so that they can act or respond a little bit differently while they are in the community?” Hedrick said.

They want to identify the root of the problem, which could be poverty or mental health.

“It’s hard to ask a kid to go to counseling if they don't know if the lights are going to be on when they go home tonight," Hedrick said. "Not every kid wants to go to a school social worker, or a school physiologist to talk about what's going on in their life, right? They may not feel comfortable."

Other problems, coincide, with social media and music that sensationalizes, drugs, guns, money and violence.

“You already have the mental health aspect of it. And then they feel like they need to compare it with what’s going on, on social media with the violence, and staying on top and looking the best and not letting people disrespect you," Goshon said. "Everybody wants to be the alpha these days. Alpha behavior, for our community, is usually shown through violence.”

The goal is the identify the problem so they can get to the root of the issue that’s driving the violence.

"It’s difficult because I think the reason behind it is so buried sometimes and the root causes don't seem obvious,” Velopulos said.

Velopulos aims to destroy those teachings when the kids are most vulnerable, in the hospital bed.

"The whole idea behind a hospital-based program is that we reach people at a vulnerable moment when they're more open to changing the direction of their life,” she said.

This program at UCHealth is called At Risk Intervention and Mentoring Program, or AIM.

"If I've just fixed their physical injuries and haven't addressed the whole person and everything that led to this then I don't feel like I've done my job,” Velopulos said.

As she tends to the physical wounds other outreach workers like Goshon help heal the mind.

"When I see a teenager he's going through these things, shot, stabbed, beat, or the perpetrator of it and I try to talk to them they're just locked in. They don't want to talk they stick to the G-Code what we call it,” Goshon said.

The G-Code is essentially unwritten rules of the streets. No snitching, no testifying, no cooperation with law enforcement. Staying loyal and true to the code is like a religion.

Goshon is familiar with the G Code because he once lived by it.

"I'm an ex-gang member. And I still keep a lot of ties with the gang. And I'm just like damn, man we fooled these kids up. And we messed them up," Goshon said. "To be honest, I'm almost burnt out here. It's a lot," he said.

We asked Goshon to reflect on how it feels to be burnt out working with youth knowing that he put others through the same struggles he's experiencing.

“I'm tired of seeing kids all opened up, open wounds, damaged, and it's just becoming too much for me," he said. "If I save their life and don't give them the opportunity to live their full life then I haven't done my job either."

Those working to prevent gun violence don't know what to expect this year after seeing increases in crime with no additional resources.

“There needs to be a level of prevention so that any family or young person that is experiencing these issues, at the first sign of a problem, can get help," Hedrick said. "Secondly, it’s all that back-end system. We have young people that are coming back into our community how do we support them."

With 2023 underway, those working with youth say they don't know what to expect, but they continue to hope for change.

"Realistic hope is that it [violence] decreases just a little bit. I'm a firm believer that you chip off a little bit at a time and we can get to a point where it's nonexistent," Goshon said. "I would like it to stop as a whole, but I know it’s not. I feel like if we can catch some of these kids before they transition into adulthood, we can start working on breaking the cycle."

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Investigations & Crime