COSTILLA COUNTY, Colo. — Ed McLaughlin was 15 years old when he saw the Rocky Mountains for the first time.

“I went to Philmont Scout Ranch, south of here, and hiked and fell in love with the area,” he said.

Years later, McLaughlin’s brother bought a lot in the Forbes Park neighborhood in Costilla County, nestled near the Spanish Peaks in southern Colorado. McLaughlin and his wife Kathy visited and fell in love.

“I’ve always wanted to live in a log cabin and live out in the mountains and stuff…it was a dream,” McLaughlin said.

The couple purchased a lot 27 years ago and built a home. McLaughlin continued his business designing and building log homes for others in the area.

Then one year ago, everything changed. The Spring Fire ripped through Forbes Park.

“The biggest problem with a place like this is you dream about it,” McLaughlin said. “And you dream about it a lot and you don’t always see reality.”

The McLaughlins weren’t cavalier about the risk of wildfire. McLaughlin has degrees in wood science. It was his business.

The couple frequently mitigated the risk on their property, cutting back trees that were too close to their home and ensuring their home had what firefighters call defensible space.

“We did everything we could and so did a lot of our friends to ameliorate the area and make sure that we didn’t have fuel for a fire,” McLaughlin said.

THE FIRE

“I came out and I smelled the smoke and I said ‘I think someone’s barbecuing,’” Kathy McLaughlin said.

Ed and Kathy McLaughlin had been spending time with their 7-year-old granddaughter.

“Ed said ‘oh my gosh look’ and in back of us here there was a huge plume of smoke,” Kathy McLaughlin said.

Soon after spotting the plume of smoke, the pre-evacuation order came.

“At that point they said just be ready to leave,” Kathy McLaughlin said.

Then came the order to get out.

PHOTOS | Spring Fire burning in Costilla County

“We honestly thought we’d be back,” Kathy McLaughlin said. “We didn’t realize that this was it.”

As the couple ran to gather as much as they could, their granddaughter didn’t want to be left out of their sight.

“She said ‘am I going to die in the fire?’ and ‘what’s it like to be burned up?’” Kathy McLaughlin said. “We were trying to gather things and she didn’t want us to leave her.”

The McLaughlins packed what they could and went into town. They were staying at a motel.

The next morning a friend came to see them with tears in his eyes.

“He said your house is gone…someone told us in the park that it’s gone.” Kathy McLaughlin said.

"I said something to my grandson I probably shouldn’t have said,” Ed McLaughlin said. “I said ‘I hope it burns to the ground’ and I didn’t mean that in a mean sort of way. I meant I didn’t want to come back to find a half-burned house that I’d have to fix up.”

Ed McLaughlin’s wish came true.

“It was totally destroyed,” he said. “There wasn’t a thing left.”

THE WILDLAND URBAN INTERFACE

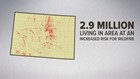

The McLaughlins live in part of Colorado where the risk of devastating fire continues to grow: the wildland-urban interface.

“The wildland-urban interface is where our natural areas – our forests and grasslands -- meet where we are: homes, businesses all that part of modern living,” said Mike Lester, Colorado’s state forester.

It’s an area of our state that has exploded with growth over the past few years, adding nearly a million people in a five-year span, according to Lester.

Of the more than 5.5 million people living in Colorado, the state forester’s office estimates 2.9 million live in the wildland urban interface.

“I think that Headwaters Economics estimates we’re only about 25 percent built out in the wildland-urban interface, so there’s that figure,” he said.

And that zone, close to the wilderness, is more at risk of fire than ever.

“We haven’t been taking good care of our forests or we’ve not had the resources to take good care of our forests, so we have some forest health issues,” Lester said.

Forests have become denser, as more people move toward them and the fires that used to naturally burn away some timber have been suppressed to save homes nearby, according to Lester.

“We have suppressed fire pretty successfully since about 1910 and in doing that we’ve taken like Ponderosa Pine, which normally grows in park-like stands, and now grows in a thick stand,” Lester said.

Where fire doesn’t burn, Lester said a lack of resources means forests aren’t seeing the kind of management they need.

“We used to have a lot of sawmills in this state,” Lester said. “We have a lot fewer now, so you’ve lost that management aspect which can replace what fire can do.”

The market for forest products is weaker in Colorado than it is in other parts of the country.

“If you’re a landowner, a sawmill’s not coming to you and buying your timber,” Lester said. “They’re offering you a service – if you give them a certain amount of money they will remove those trees for you.”

Lester said both of those reasons, plus a naturally longer fire season, creates a deeper risk for destructive fires.

“Our biggest fire in Colorado was the Hayman Fire, which was roughly 130,000 acres,” he said. “There are experts who will tell you…or who will postulate that that probably won’t be our biggest fire unless we do something.”

The Spring Fire, which burned last year in Costilla County and destroyed Ed and Kathy McLaughlin’s house, burned 108,000 acres and was the third-largest wildland fire in state history.

The risk of a fire like that is all over, according to Lester.

“You’ve got communities all over the mountains, we’ve got communities built into canyons, we’ve got communities built into canyons that are open to the prevailing winds, you’ve got thick forests – those are recipes for disaster that doesn’t have to happen,” he said.

COMMUNITIES AT RISK

Closer to the Denver metro area, Bill and Samera Baird spend several hours each week working on their property to mitigate the risk of wildfire.

They live in Happy Canyon, a neighborhood north of Castle Rock, nestled in a canyon east of Interstate 25. With its thick brush, South Metro Fire has identified Happy Canyon as one of the biggest risks in the metro area.

“Walk around and you see the trees – they’re everywhere and we love them and we also realize that the fire risk is pretty high,” Samera Baird said.

The couple will admit when they first moved here from Alabama 10 years ago, the didn’t realize the risk. It took images of destructive wildfires, like the Black Forest Fire near Colorado Springs, to help them understand.

“You watch 200 homes getting destroyed in three hours and that gets your attention,” Bill Baird said.

The couple got in touch with South Metro Fire to ask about the fire danger in Happy Canyon.

“I’ve heard it would be a one-day event,” Bill Baird said. “It would move very rapidly.”

Happy Canyon is surrounded by brush and there is only one way in and out of the neighborhood.

“Optimists would not want to think that something bad can happen, but it’s very possible that it can happen…it has happened in similar neighborhoods in Colorado since we’ve been here," Bill Baird.

The Bairds started to mitigate their risk, as directed by firefighters. Each week the couple spends hours outside, clearing gamble oak and putting it in slash piles. One a year, Baird pays a man with a Bobcat to grind up that slash.

They removed trees around their house and added green space.

“We see the images (of other fires) and we think that could be us,” Bill Baird said. “But I also have some security knowing that we have done a whole lot.”

MITIGATING RISK

While the Bairds spend about $1,000 each year and countless man hours clearing brush, they admit, some of their neighbors don’t.

“There are about 200 homes and each of them is unique like ours and some people have done work to mitigate the risk of fire and some people have done less work to mitigate the risk of fire,” Bill Baird said.

He wishes more people took mitigation seriously. And Lester said that would help the problem.

“What happens is if you do defensible space, it increases the probability that your home would survive a wildland fire,” Lester said. “Now if your neighbor does it – it increases it a little more. Your other neighbor does it – it increases it a little more.”

“One person does it – it’s not that it doesn’t make a difference,” he said. “But it makes a lot more of a difference if the whole neighborhood does it.”

But even Lester admits, mitigating individual homes is only the first step.

“There’s going to need to be an investment in more resources in order to make this happen,” he said.

REBUILDING

The McLaughlins mitigated their property. So did many others in Forbes Park.

Neighbors there said the Spring Fire burned homes that had done extensive mitigation work and didn’t burn some homes that hadn’t mitigated at all.

“There’s so many people that come up here and they just say ‘I want to get out of the heat…I want to get up in the mountains,’ but they don’t realize it’s not easy to live up here,” Ed McLaughlin said. “You have to keep your wits about you and you have to do the right things…and hopefully you rely on your neighbors a little bit.”

Ed and Kathy weren’t sure they wanted to rebuild inside the fire zone until one day when Kathy was cleaning up the debris from their home.

“I started raking and all of a sudden this little white thing came up and I thought what is this? And it was one of my pieces to my Nativity set and I raked again and there was another one and another one,” she said.

She found every piece of that set that day. And the McLaughlins said that was the day they decided to rebuild their home.

The shell of their new home is in and the couple expects to move by Labor Day. They hope to host Christmas for their family.

“Now we’re thinking we’re going to build this place and give it to our kids… it’s here for the family forever," Ed McLaughlin said.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS | Local stories from 9NEWS