GRAND COUNTY, Colo. — The East Troublesome Fire scorched more than 87,000 acres of land in Grand County in a day on October 21st.

At the time, the amount of land it burned would have been enough to make it the 4th largest fire in the state’s history.

Its sheer size and speed in which it grew shocked everyone, from locals who had to evacuate to first responders and scientists.

The impact left behind sits with those who study fires, respond to them and those whose work is to prevent them.

This fire was an outlier

Janice Coen, a Project Scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, spent much of her career studying and modeling wildfires.

When it came to the East Troublesome Fire, she said that 2020 was very active from a fire standpoint in Colorado and California because much of the Southwest was covered by a large and persistent vapor deficit, setting the background conditions.

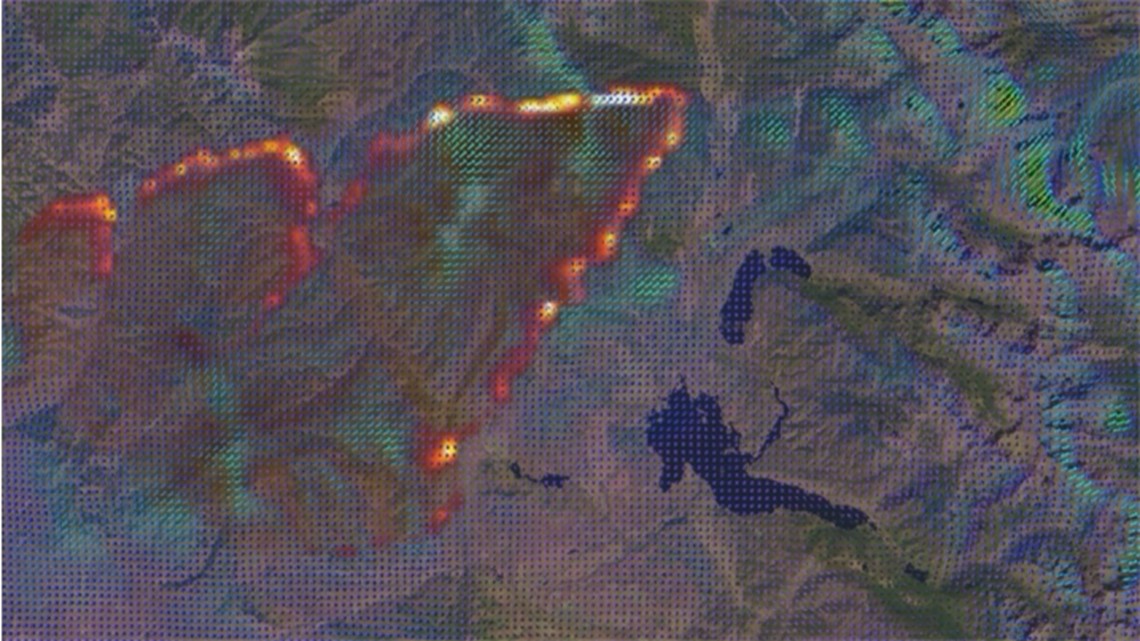

“And we find that these large events occur with these large daily fire growth patterns. When a number of things come into alignment, that terrible term, a perfect storm, if you will. On top of these background conditions, there were local weather patterns that enabled some of these wildfires to develop, as well as a fortuitous ignition at the wrong place in the wrong time,” she said. “But on one particular day, it laid in a river of strong winds that allowed it to grow over 87,000 acres in a day from an area in Granby, pushing it to up over the top of the continental, spotting over the continental divide and then threatening Estes Park.”

She said the fire started out with a two-pronged approach, but because of the winds it sat in, it spread rapidly, allowing the fire line to form a spear-type shape, with a tip coming over the top of the divide and sending spots over the other side of it.

“It was it was definitely an outlier,” Coen said.

She designed a simulation of the East Troublesome Fire, which was done over the Summer after someone investigating home destruction asked her a question about the fire behavior, which she said raised questions about the winds that were generated during the fire.

Right now, Coen said what isn’t captured well by current operational weather models are the fire-induced winds created by the fire, which she said are often the most dominant winds in certain events.

“This is obviously a wind driven event, a fire that occurred during very windy conditions that spread the fire. But the other end of the spectrum, there are many fires that grow rapidly that start in conditions where the winds are very weak and there are strong winds within the fire, but they are generated by the fire itself,” she said. “And these both types of fires are ones that current tools that are generally used operationally are not very good at because they have limitations."

"They’re based on methods that have been around for a very long time, and they both miss something about these very large fires," Coen said. "And that is the complexities of wind maxima that occur as air flow goes over complex terrain, there are small scale dynamics that occur that boost the wind speeds up another 10 or 20 miles per hour.”

When reproducing a fire, Coen said that often she could test the sensitivity to certain factors, including fuel loads or fuel moisture.

Fuels in a fire can be anything from vegetation to beetle kill.

“And often these commonly attributed factors aren’t as important people as people think that the fire spread was largely determined by the wind and off and fine scale circulations that aren’t apparent in our weather station network, which is quite coarse and sparse or due to the fuels,” Coen said. “But the history of fire in forestry tends to make fuel seem like the most important thing, because that’s the factor people understand, but as we learn more about the weather, we see the much more impact on fire events from from the winds and the interaction with the fire.”

Coen said the research would transition into more practical uses with progress to model fires in the community.

“I get contacts nearly every day from technology providers who want to be able to provide fire forecasts to the public. We’re getting better and I think within a decade we should be able to predict not only where a fire is going to go and how fast, but other important factors like where these large whirls are going to form. And I think there’s a lot of promise and we should see a lot of development in the next decade.”

Wind-driven but fuel-fed

For foresters in the area, their primary role is to eliminate the fuels that fuel a fire like the one seen last year.

“So what we’re seeing right now is the forest unraveling. In other words, the trees are falling over because of rot at the stump, the same at the ground level, and they’re easily blown off or they’re starting to accumulate on the ground.” Ron Cousineau, a forester and area manager for Northwest Colorado’s branch of the Colorado State Forest Service said.

“They’re called thousand our fuels. And that means they take about a thousand hours to equalize with the surrounding air mass," Cousineau said. "Thousand hours is a lot of days, it’s a lot of weeks. So they don’t really equalize with the air mass. They just continually dry. And most of the fires we’ve seen in the last six, seven, eight years in this part of Colorado have been in beetle kill. And - the result is fires that are very difficult to suppress.”

While Cousineau acknowledges that the fire may have been wind-driven, he adds that he believes it was fuel-fed.

“And you know, these fuels do exist, so they were there to be consumed. It created a very intense fire, a very impactful fire and one that just wasn’t going to be easily suppressed,” he said.

In part, foresters like him and Matt Schiltz identify priority landscapes and then address the fuels situation within that landscape.

The amount of fuels they said is a problem that extends further than just what happened with the East Troublesome fire.

“And one other thing that’s kind of been contributing to the whole fuel loading issue as well is as these forests continue to blow over, you’re getting more sunlight hitting the ground and we’re seeing a lot more shrubs and grasses and young trees starting to grow up underneath that. So we have even more fuel growing in these environments as well,” Schiltz said.

“So what happened in East Troublesome Fire as you had just extremely heavy fuel loads all across the landscape - and these fuel loads were very resistant to suppression efforts," Schiltz said. "And one day, when the fire blew up, it was a particularly dry, windy day. And just the combination of heavy fuel loads, strong winds, dry conditions and then atmospheric conditions that higher up in the atmosphere created just this perfect storm that caused the fire to blow up.”

The fire, he said, created fresh and new demand for their services but hopes this time that demand can stick around as they work to remove fire fuels from the area.

“That’s what keeps me busy every day is just finding solutions and whether that’s, you know, using any, any mechanism in our toolbox that we have, whether that’s going to be timber sales, finding grant money to go and pay a contractor to physically cut and remove that biomass. Working with communities to have them take on their own initiatives and their own efforts around their homes. Working with multiple partners, whether it’s water providers, wildlife agencies, we work quite a bit with the Forest Service and the BLM through the Good Neighbor Authority and just trying to really increase the scope and the scale of treatments on the landscape,” Schiltz said.

Cousineau also acknowledges the difficulty of the job, considering the staffing levels of the forest service.

“We’re working very hard these days to try to increase our influence on the landscape and know the Colorado State Forest Service is a small agency. We’ve got 120 people statewide. That’s everybody. And with that few people, it’s hard to do the work that needs to get done where we’re certainly behind the curve,” he said.

Its impact on first responders

Some days are busier than others at a fire station, but at this time one year ago, fire chief for the Grand Fire Protection District Brad White still recalls the feelings around the speed at which the fire grew.

“And, you know, I think it stunned and shocked, not just the locals, but, you know, spent a lot of time talking with those folks on these incident management teams that do a lot of big fire and none of them had seen anything like this. And they were as shell-shocked, trying to pick up the pieces as we were as local firefighters,” he said.

But before the fire happened, White said steps were taken to get their staff experienced on other fires.

“I think starting 2015, you know, started putting an engine available, you know, nationally just to get those guys out and get them experience on other fires. And that program started pretty small and started with a seasonal engine boss and then supporting with the volunteers and the resident firefighters we have here,” he said. “And in 2020, we had actually had a, you know, kind of taken the next step and we’re off. We’ve got a full time engine boss, wildland coordinator. And we hired in 2020 a full time engineer just to kind of ensure that track was was ready and good to go and then fill in the back seats with with some of the other firefighters this year.”

Initially, he said that it was a goal to hire out an entire truck dedicated to fighting wildfires in the next several years, but that happened this year.

“You know, I worked with our board of directors and we actually went ahead and hired out the entire truck. So a couple of seasonal three seasonal firefighters, plus our full time engine boss, you know, just for the intent of starting to develop some of that long term skills and knowledge base,” White said.

He adds that the fire prioritized his team getting more engaged with fire control at a higher level and integrating technology.

“I think in the field it’s, you know, we’re continuing to do best practices there. You know, I think, you know, we got to remember that this is a one in a million fire and we still have every year all these small fires that we’ve got to fight and get put out before they get to that size, right? And so that carries on. But I think a at a higher level, you know, we’re trying to get a little more engaged with what’s going on at division fire prevention control and their center of excellence, you know, the technology they’re looking at,” he said.

“We’ve got a local IT nonprofit that is really trying to work and help supplement and see what they can do as far as instituting some technology," White said. "And so we’re trying to reach out and see, you know, what, we need to be involved with there, what we can contribute and hopefully get down into the field level, you know, in the next few years here.”

Also, he said there’s a greater emphasis now on working with homeowners in the area.

“You know, the other side is still just picking things up with our local homeowners and and homeowners associations and really sort of, you know, hitting them with, you know, we’ve got to get defensible space in mitigation, which of course, has been an ongoing project for for many years, but definitely a lot of interest this year,” White said. “You know, internally, our staff has spent a lot of time meeting with homeowners on what they can do on their property, meeting with homeowners associations, what they can do to become fire wise and really give themselves some, some good fuel breaks and some places for firefighters to work.”

For the Grand County Sheriff’s Office, Sheriff Brett Schroetlin explained that their goal with evacuations is to do them in a slow, methodical and planned process ahead of time.

Throughout the county, thousands of homes were under evacuation orders during the East Troublesome fire.

“And unfortunately, in the last few years, we’ve become very experienced in evacuations here in Grand County, starting a few years ago with the Silver Creek fire in 2018, and then the Williams Fork fire and the East Troublesome fire in 2020. Unfortunately, we did a lot of evacuations,” he said. “And so using the fire science and the fire behavior, maps and personnel, we look at what our potentials are and we rely on different action points or discussion points to decide when evacuations need to occur and how those evacuations need to occur. And so it’s kind of done in a pre-planning phase, but also that can also change depending on fire behavior, and things can happen slower or quicker, depending on what we’re seeing.”

After the fire, the Sheriff’s office formed a new evacuation plan for the entire county, breaking up the county into 94 evacuation zones.

“And so if an incident like this occurs in the future, we actually have a plan in place. Our citizens are aware of where they actually fall within the evacuation area mapping and those designated areas and numbers can be referenced by citizens and by our deputies, which also increases that effective communication,” he said. “When people are in an emergency, you know, number one our first responders during a critical incident like this, it doesn’t take long before we run out of manpower and staffing. And so by doing these ahead of time, it allows us to quickly push out information."

"Secondly, as the community during a critical incident, if you already know where you will fall in the system ahead of time, then it saves half and to try to figure that information out on the fly," White said. "And so if the community takes a little bit of time and learns about their evacuation area and if we’ve previously identified these evacuation areas, then ultimately it’s going to speed up the evacuation process, which ultimately hits our end goal of evacuating people in a quicker and efficient manner, which ultimately results in saving lives.”

RELATED: ‘I don’t know how they did it:’ Retirement home looks back on East Troublesome Fire evacuation

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: 9NEWS Originals