DENVER — Editor's note: This interview was conducted in Spanish, translated into English and edited.

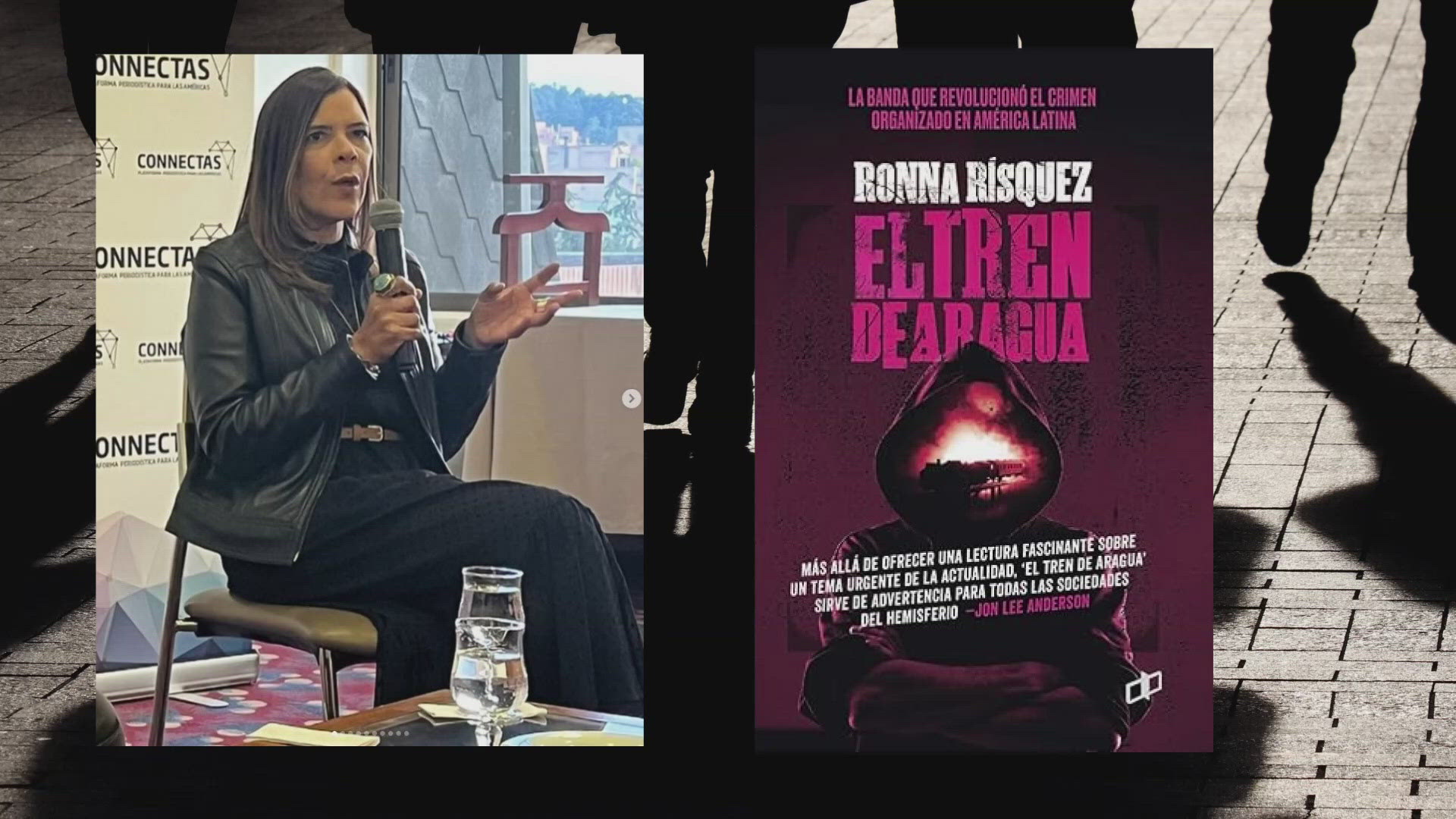

After spending three years interviewing gang members, their victims and criminal investigators, Ronna Rísquez published an in-depth book about the Tren de Aragua prison gang.

As the gang makes headlines in Colorado and nationwide amid a politically charged news cycle this year, 9NEWS asked Rísquez various questions about the gang’s origin, motivation and how media coverage of the gang is impacting migrant communities.

Rísquez shared that the gang began around 2014 in the Venezuelan state of Aragua, specifically in the Tocorón Prison. Last year, The Associated Press reported a raid on the prison, which the gang controlled, and revealed a nightclub, a zoo and roughly 200 women and children living on the prison grounds.

9NEWS: Why the name Tren de Aragua?

Rísquez: Within the prison, the structure of the criminal group, they call it a "car." That is, instead of saying, "We are a gang," or a cartel, they say, "We have a car." That is, "We have a car" is the structure within the prison. So, when this structure comes out of the prison and starts moving outside of the prison, in this case, expanding through Venezuela to Latin America, they call it a “train.”

At the time when the group was born, approximately 2014, in Venezuela there were already several gangs that were called “Train.” So, for example, there was the Tren del Llano, the Tren del Norte, the Tren de Oriente. So different gangs had been naming themselves “Tren,” and all of these gangs were related to the prisons, or the leaders were people who had been in prison.

9NEWS: How big is Tren de Aragua?

Rísquez: When I did this research, there is no scientific basis, but I calculated that there were about 3,000 members who were part of those who were imprisoned in the Tocorón prison and those who were operating outside the prison, both in Venezuela and outside of Venezuela.

9NEWS: What is their main type of crime?

Rísquez: In my research, I identified at least 20 crimes. The most important are the trafficking of drugs, extortion, trafficking of migrant women for sexual exploitation, trafficking of migrants, illegal mining, contract killings along with another series of activities. They also participate in transnational drug trafficking, but more as handlers of the drugs.

9NEWS: Is there any indication that the Venezuelan government is encouraging some of these gang members to leave the country?

Rísquez: Not at all. There is no indication, there is no encouragement. The government is not saying, “Go to the United States.” They also don’t open the dungeon doors for them to leave.

But one thing has to be clear: Venezuela is still experiencing a complex humanitarian emergency, a very serious political and social crisis. This crisis affects all Venezuelans who — since 2014, 2015 — have been in some kind of survival condition. And, what happens? This affects people who are in prison even more.

So, what is the option for many of these people? Well, trying to leave the country in search of opportunities. When they arrive in other countries, they find that it is not easy and perhaps, unfortunately, some of them will return to the circle of crime.

9NEWS: As a Venezuelan, what do you have to say about the consequences that Latin American migrants are having to face due to the discourses centered around Tren de Aragua?

Rísquez: Venezuelans are being stigmatized, when in reality, the majority of Venezuelans who have arrived in the United States and who are spread around the world due to the disgrace that is being experienced in the country are people who have left to work, to survive and look to contribute the best of themselves to the communities to which they have arrived. So, to label them as criminals, to label them as a criminal group, I think that’s very serious and very harmful.

I also think it’s very serious that this type of group is given a level when it is mentioned by a former president, when it is mentioned by the governor of a state, when it is mentioned by an authority. It’s like you’re giving some power to this group as well, you know? You’re promoting them, you’re giving them more power than they may actually have. And I think that is something that we also have to be careful of, because you’re putting them on a level where they may not be.