PUEBLO — Though it's just water, the Arkansas River through Pueblo used to be much more.

"Many people don't know this story. They don't know that the Arkansas River just south of this museum was once the border between US and Mexico," said Dawn DiPrince, Chief Community Museum Officer for History Colorado.

Though it's just a line, it impacted Pueblo and the western United States forever.

"It is what changed the border from the Arkansas River to the Rio Grande River," said Jose Ortega, exhibit and collections coordinator.

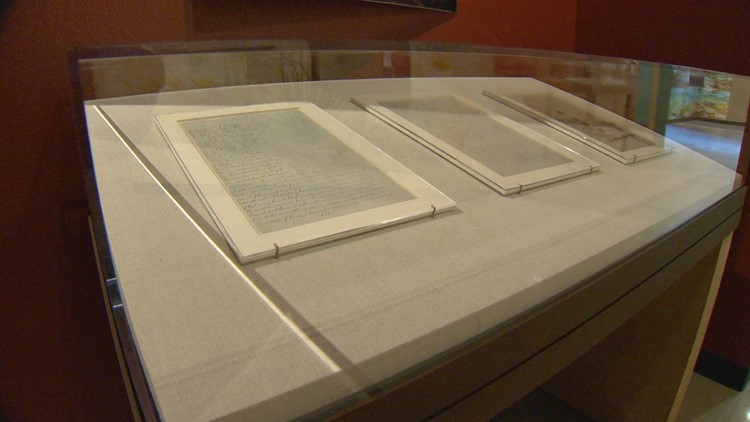

Though it's just a piece of paper, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is a part of history. The Treaty is now on display at the El Pueblo History Museum in Pueblo under the watch eyes of DiPrince.

"I believe that this document is very meaningful to the people who live in southern Colorado," DiPrince said.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War. Signed in 1848, the Treaty forced Mexico to give back land in parts of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Nevada, California, and Utah in exchange for $15 million in war reparations from the United States.

"It's important that this document's here in our backyard because it defines our backyard, Ortega said.

Ortega needs to make the Treaty remains intact considering it's age and delicate condition.

"We had to regulate temperature. We had to make sure that the case and the relative humidity didn't fluctuate over three above and below," Ortega said.

The Treaty rarely leaves the National Archives in Washington D.C.

"We had the audacity to ask," DiPrince said.

The tilt of the display needs to just right, DiPrince says. She adds that amount of light shining on the case needs to be monitored.

"It's very delicate," DiPrince said. "It is made out of fibers."

Though it's just history, the Treaty is a source of pain for the family of John Valdez.

"That impacted not just my ancestors in the northern part of New Mexico, but all New Mexico," Valdez said.

The Treaty impacted lands that were once a part of a Mexico and making them a part of the United States. Valdez said his family's land ownership rights were nullified.

"Other individuals from the east, you know, came into New Mexico and some say, our people would say, swindled the Nuevo Mexicano out of their property," Valdez said.

The retired teacher and part-time genealogist said the Treaty took away everything from his family.

"Lands that people were able to go hunt, get firewood, get timber to build homes," Valdez said. "You know, we're survivors. That's what we are today, but that's what my parents were, my grandparents, my great-grandparents, you take that back till the 1800s and you say well, wow, how did they? How could they?"

Valdez had never seen the Treaty in person. When he looked upon it for the first time, he didn't know what to say.

"It's an ambiguous feeling of where I am with the emotions right now," Valdez said.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo is on display as part of the Borderlands of Southern Colorado Exhibit at El Pueblo History Museum. The Treaty will be on displauntilll July 4.

"Stories are told, but it's the objects that we possess, the documents we possess that offer proof and verification," DiPrince said. "This really is our history."