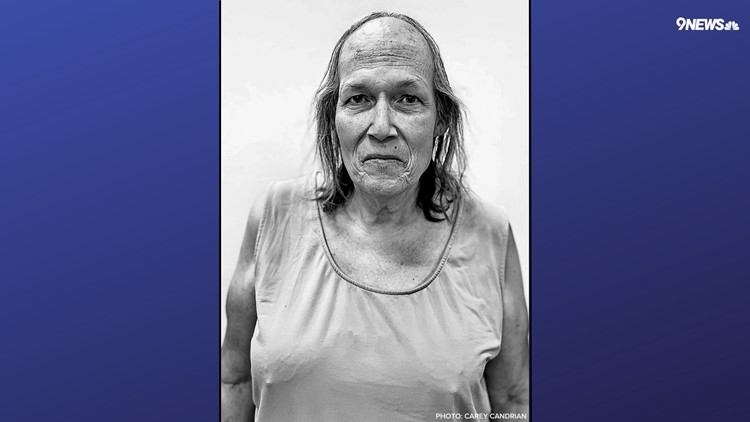

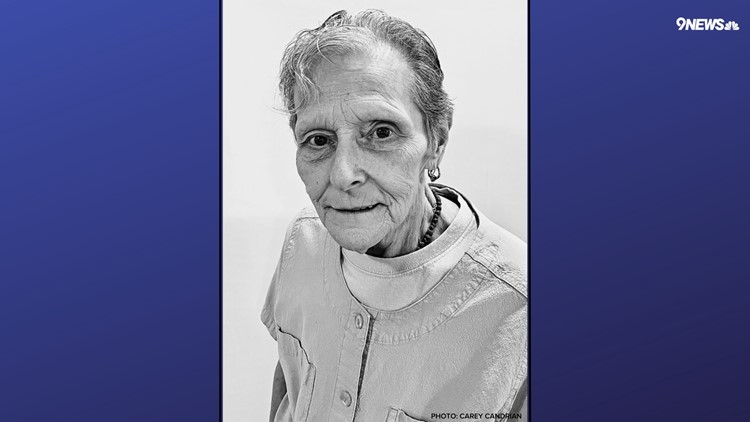

AURORA, Colo. — A University of Colorado researcher who's dedicated her career to studying end-of-life care has focused her camera on elderly people in the LGBTQ community in hopes of sparking a change.

Carey Candrian, a researcher and associate professor at the CU Anschutz medical school, received multiple grants to work on the project titled Eye to Eye, which is on display at the Fulginiti Pavilion for Bioethics and Humanities on the CU Anschutz campus.

"I think it’s easy to look away when you hear general numbers about groups of people, but it’s much harder when you see someone, when you know them, and even love them," Candrian said. "So this was the idea, to really be able to meet some of these people behind the data."

The American Heart Association estimates that 56% of LGBTQ adults experience some form of discrimination from a health-care professional. For those who are trans or gender non-conforming, the statistic goes up to 70%.

"The big one is the stress of hiding something so core of who you are can take up to 12 years off their lives, and this is from two years ago from the Harvard Medical magazine," Candrian said. "I would share some of those statistics when I disseminate my research to assisted-living communities, to hospices, to hospitals and it just didn’t have the impact that I really wanted it to have to generate conversations that could actually lead to change."

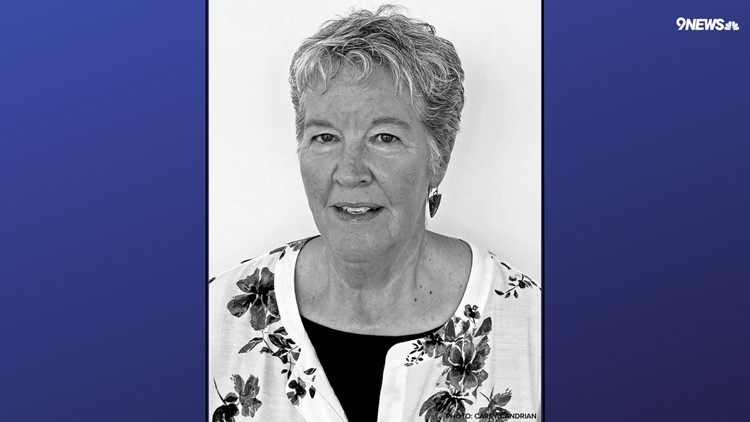

She put a call out to elderly people in the LGBTQ community who were willing to share their experiences when seeking any kind of care.

She connected with nearly three dozen LGBTQ women between the ages of 59 and 85 years old. She interviewed them and photographed them to humanize issues that she said often go unreported.

New CU Anschutz exhibit 'Eye to Eye' puts focus on older LGBTQ women

"The majority of older LGBT people grew up thinking being gay or lesbian was unthinkable," Candrian said. "It was dangerous, even illegal, in most places, and for that reason, a lot of them have honed what I call a habit of silence about this core part of themselves.

"These are some of the bravest, strongest, most courageous women I’ve ever met, and they’ve all experienced those disparities, and they’ve all experienced the discrimination, estrangement from family, lack of social support, lack of being acknowledged when someone’s partner dies, and yet here they are, willing to really be brave enough of who they are and choose that knowing the cost that comes with that."

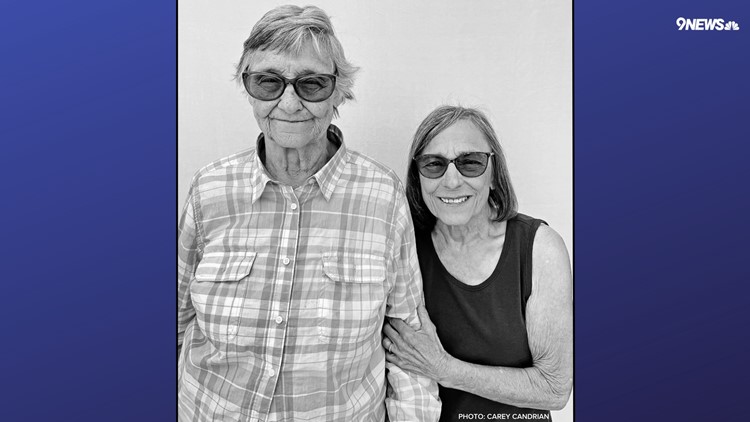

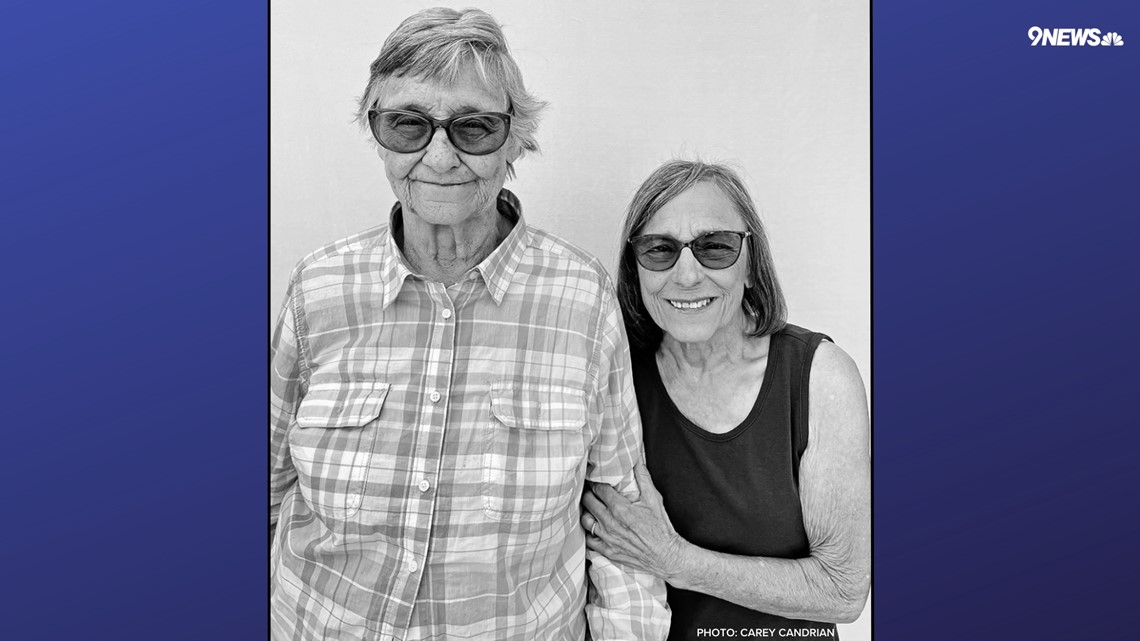

Nancey Johnson Bookstein

and Joan Johnson

Nancey Johnson Bookstein and Joan Johnson sat in their Westminster home and held each other's hands. The pair have been together for 45 years, but they stared at each other as if they just said "I love you" for the first time.

"She was the only one that ...," Nancey began to explain.

"Stole your heart," Joan finished.

"Absolutely. Absolutely stole my heart," Nancey said with a nod and a smile.

Nancey and Joan met while working at a Denver hospital that no longer exists.

"We just became friends and colleagues, and then she chased me until she caught me," Nancey said with a smirk.

"Unfortunately, yes it is true," Joan added with a laugh. "I have to admit to it and live up to it, but yes. I know there was some kind of bond and had been before I ever met her."

The pair were inseparable but said they kept their relationship professional at work. Joan said that didn't prevent her from being fired.

"I got fired from my job because they said we were holding hands in the cafeteria," she said.

"We never went to the cafeteria," Nancey added.

"So one day I walked in and they said goodbye. I knew it was coming, I knew it was coming," Joan said.

Nancey never "came out" while her mother was alive and was "outed" by colleagues at work. Joan revealed her relationship to most of her immediate family, but her daughter found out through someone else.

The two have have been public about their relationship and marriage for years now. They've created a family and have been widely accepted at their church, but the repercussions of their relationship still haunt them.

Joan is 86 years old and sick.

"Joan’s got leukemia," Nancey said. "We are blessed by the fact that we’ve been given time to end this journey together and to spend time together.

"We would have loved to have moved into an area for seniors, and we probably could do it, but only undercover," she added.

"To think about going to a retirement community that we have to start all over again with, it’s just beyond our ability to deal with emotionally. You don’t know what communities are welcoming and what are not, and we’re pretty sure there will be marginalization in some form or another, and it’s just not comfortable."

Nancey and Joan are two of the participants in the Eye to Eye project. They said they hope that sharing their story will help future generations from having to worry about discrimination.

"I don’t have that many more months to be able to make a change, but if I’m still up and moving around, I’m going to do what I can," Joan said.

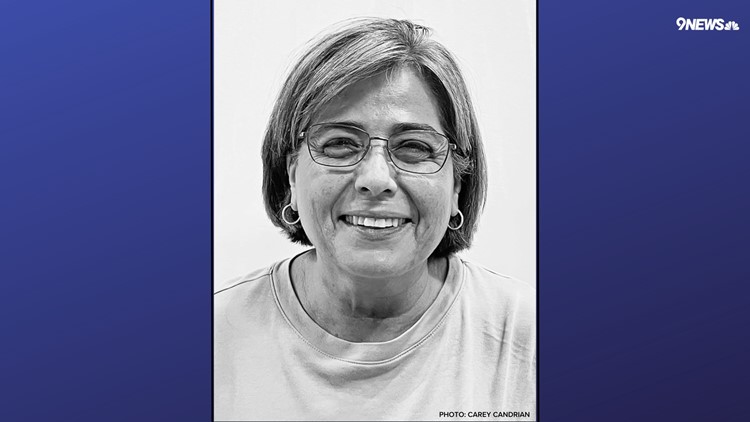

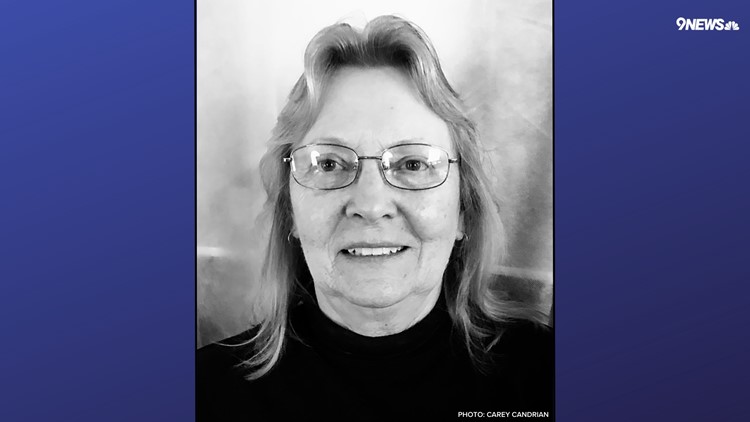

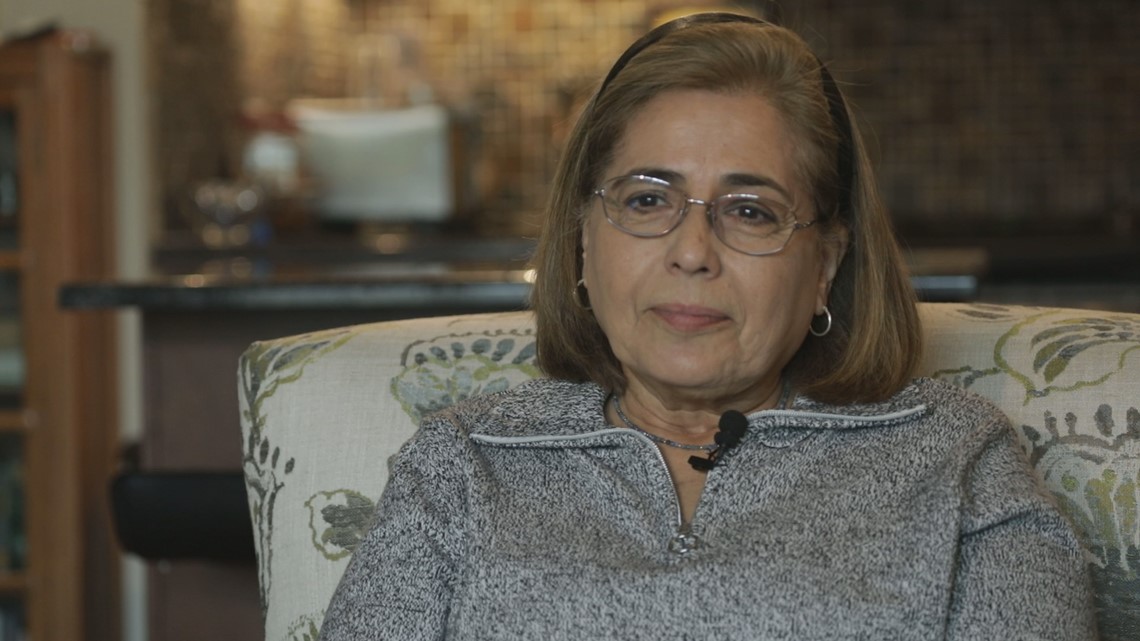

Esther Lucero

Esther Lucero sat in her living room with a smile on her face. Her eyes were gleaming as she thought about her wife, Cathy.

"To me, she’s everything," Esther said. "It was a wonderful life. There was very little that went wrong it was just a wonderful life."

The pair lived in Denver when Cathy began to get sick. The two moved back to Cathy's home in South Dakota to seek care.

"They finally found out she had T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia, which is a rare form of leukemia," Esther said. "Cathy told me one day, 'Stop telling the nurses we’re married.' She said it’s because 'they’re treating you differently, and they’re treating me differently.' So I said, 'OK', so I stopped, and that was hard to do because that was something we looked forward to that we had done, and she’s my wife."

"One nurse in particular, he was very abrupt with her," Esther said. "He genuinely didn’t want to come in the room. I would go out and get him some times and say, 'she needs your help she needs this.' "

Esther said most nurses treated her just fine, but that one particular nurse that seemed to avoid the couple was what drove Cathy to make the decision.

Because Esther was no longer the wife, she wasn't involved in treatment conversations. She said she was not acknowledged as a grieving widow when Cathy died.

Esther was approached by Candrian shortly after Cathy's death and decided it was important to share their story.

"It was a big decision," she said. "A lot of me was like, I can just get back and stay in that closet, I can just go back and live a nice peaceful life and whatever, and the more I thought about it, I said, 'Well, if I do that, it’s like Cathy never existed.'

"What I hope is that people now and in the future don’t have to go through anything or question whether they were treated differently because they were gay, lesbian, transgender, whatever they are," she said. "That’s the biggest thing I hope comes out of it."

The Eye to Eye exhibit will be on display at CU Anschutz through August.

Candrian said she hopes to move the project to another facility in Denver so others can have an opportunity to see it.

"This exhibit is certainly not going to give 12 years back to anyone’s life, but I think the one thing for people who come and see this exhibit, whether it’s online or in person, is that these women stay with them," Candrian said.

"So that next time they interact with a patient, a colleague, someone at the grocery store, a friend, a family member, they hear these women. They hear these stories."

RELATED: Colorado Board of Education debates whether LGBTQ discussions belong in lower-grade classrooms

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Latest from 9NEWS