PUEBLO, Colorado — The Colorado Department of Corrections' use of clinical 4-point restraints at state prisons is under scrutiny by a Colorado attorney who contends the practice – which is meant to prevent harm – doesn't always produce the intended results.

Meghan Baker, who's with Disability Law Colorado, is documenting the use of 4-point restraints within DOC at four state facilities for a soon-to-be published report. She said she's documented over a two-year period that DOC used the restraints 136 times. The longest stretch she said she's aware of was 39 days.

"It's supposed to be to prevent harm, and I think there's an understanding that it's supposed to be eminent and serious harm, but that's not how it happens in actuality," Baker said.

Baker's report is a part of an effort to create new state laws to regulate the practice.

Tyler Himelstieb went to the San Carlos Correctional Facility in Pueblo in July 2020 to serve a nine-year sentence for assaulting his ex-girlfriend. The 35-year-old said he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at the age of 21 and admitted he can be a danger.

"Sometimes, I would resort to banging my head pretty bad," Himelstieb said. "It would split my head open all the way to the skull and would usually get like 12 to 15 stitches at a time."

He said that's what happened on his first day at San Carlos. He said he went to the hospital and returned in a calm state. Yet, he said he was placed in 4-point restraints with his arms and legs in metal cuffs and strapped to the bed – for about 20 hours.

"So, you're basically just restrained like this for hours and hours," he said.

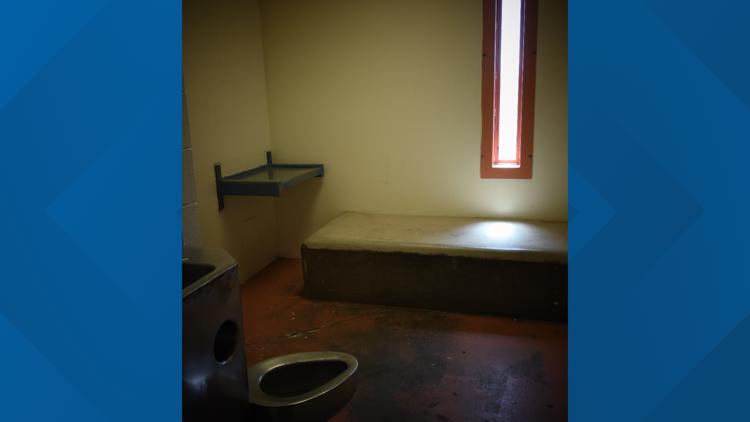

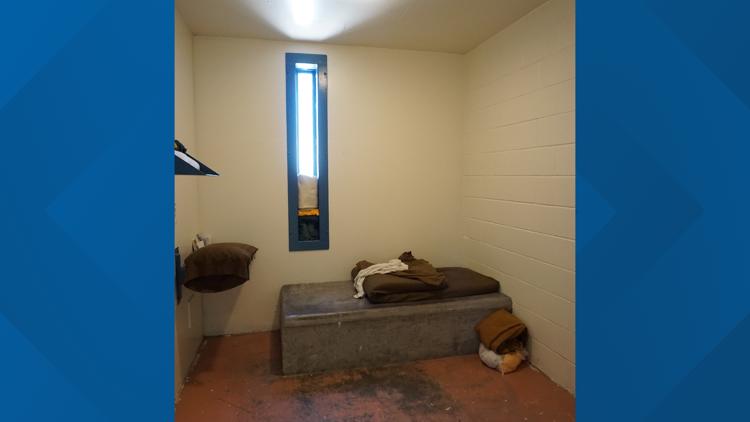

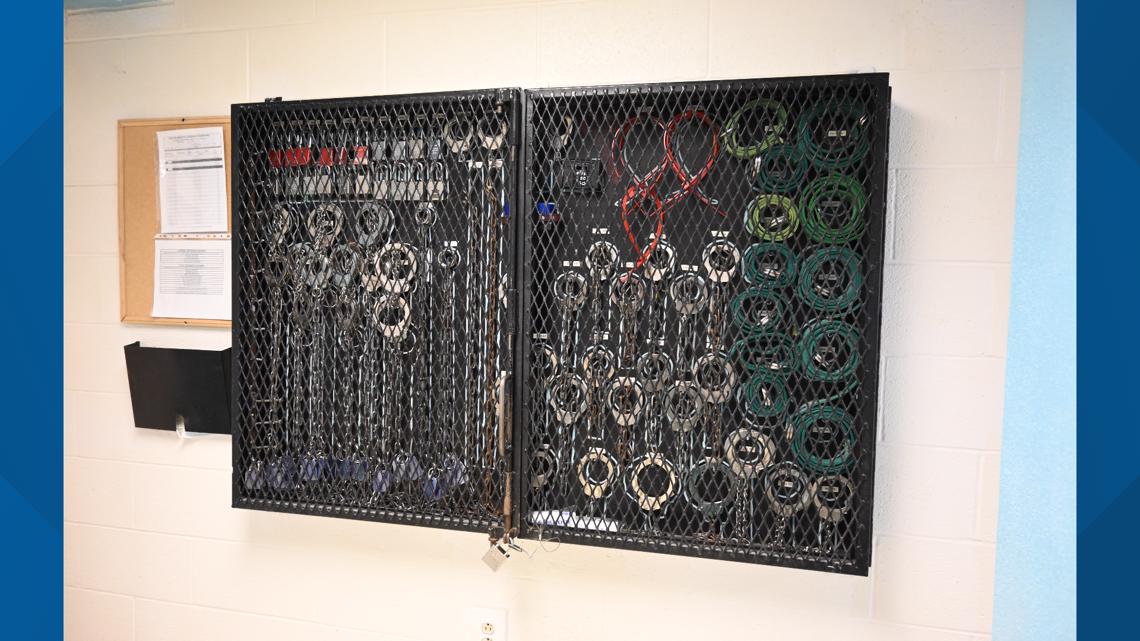

Baker went to investigate the restraint cells at San Carlos and took photographs of the metal cuffs, the bed, and what she describes as a small, dark room.

"The closest thing I can think of as to what it looks like is like an execution chamber, to be honest," Baker said.

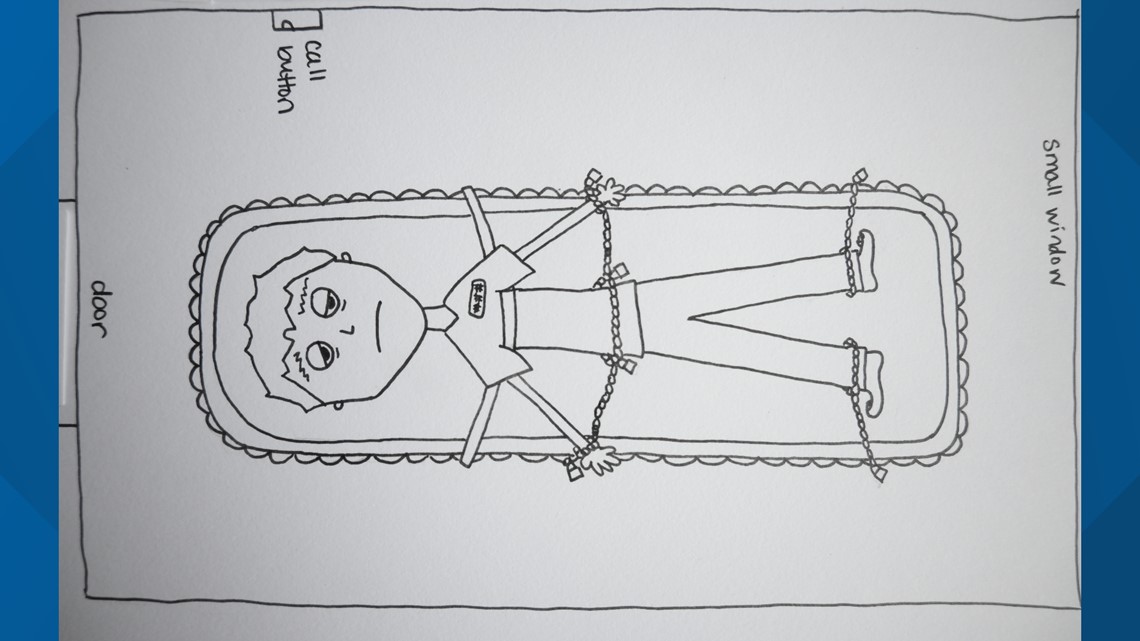

In addition to all the pictures taken by Baker and her colleagues, they also drew a diagram instead of taking a picture of the person she saw prone on his bed in 4-point restraints. Baker said they didn't take a photo out of respect.

"Just the stark ugliness of it all, I mean just as a human being walking in that room, the idea of thinking of being something that is subjected to that is unimaginable to me," Baker said.

Himelstieb said during his struggle with bipolar disorder, he has been placed in 4-point restraints about 10 to 15 times in clinical settings when he posed a danger to himself. But he said his experience at San Carlos was by far the worst one.

"I had such bad bruising, welts and slight bleeding on my wrists and ankles that they ended up uncuffing me and they put gauze around my wrist and ankles and then put the cuffs back on," he said.

Himelstieb estimates he was in 4-point restraints his first day at San Carlos for about 20 hours with an offer for a bathroom break, he said, only once every six hours.

"To put somebody through that, I believe is just torture, just blatantly torture," he said.

That was just one day.

Baker said she found reports of people who were in 4-point restraint rooms for weeks. She said she believes that in other instances, like Himelstieb's, people are placed in restraints for multiple days in a row, for 20 to 22 hours each day.

"They're doing it for hours and hours and even days and weeks at a time while not providing sufficient, meaningful intervention for the people who really need treatment, not restraint," she said.

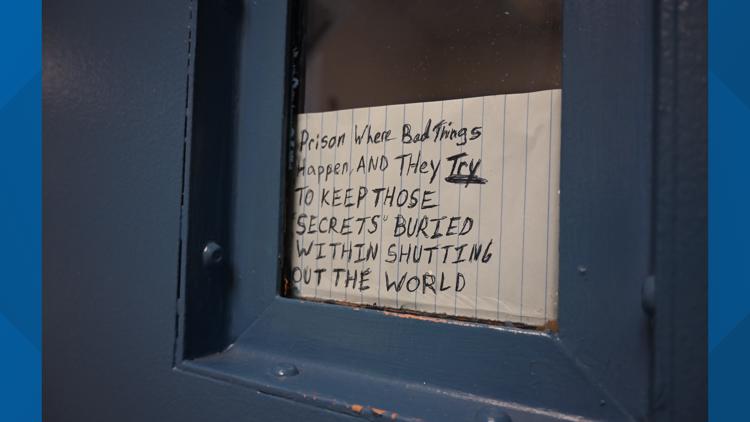

Himelstieb said the lack of documentation by DOC on 4-point restraint events is a significant issue.

"It's a big problem cause it makes it harder," Himelstieb said. "It makes it harder to let people know the excessive amounts of time that you're in there."

Baker and Himelstieb want people to remember this is being done to people with mental illness.

"You put them in restraints, and after long enough, they will start fighting the restraints and start exhibiting negative behavior," Himelstieb said. "Just even a normal person, I believe, would."

The big issue, according to Himelstieb, is that once restrained, DOC does not make it clear what it takes to get released. He said it feels arbitrary and takes away the hope of ever getting out.

"You get into a downward spiral of abuse that you can't escape," he said. "You know that's what leads people being put in restraints for such excessive amounts of time."

Baker said people need to know how to get the restraints removed.

"They don't give you clear criteria for when you're going to come off, and so there's also just no sense of control," she said.

Now on parole, Himelstieb said he's stable and improving while living with family in Aurora. Despite his experience with 4-point restraints at San Carlos, he said he eventually received the help he needed there.

"I have a tremendous fear of losing control and getting put back in 4-point restraints," he said. "I definitely have a fear of that ever happening again to me."

Fifteen days after his parole from prison, he testified at the State Capitol, working with lawmakers who are proposing a law to regulate the use of 4-point restraints. State Representative Judy Amabile, (D) Boulder, has sponsored a bill proposing change.

Baker's report recommends a mandate for the use of soft restraints like vinyl instead of metal cuffs, that prison staff check on someone in 4-point restraints at least once every two hours, and that a cap be placed on how long someone can be restrained each day. Himelstieb also wants clear criteria on how to get out of 4-point restraints.

Other states already have similar laws, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons has similar regulations and caps.

"I am sharing my story because I don't want this to happen to anyone else," Himelstieb said before the Treatment of Persons with Behavioral Health Disorders in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice Systems Committee on Sept. 29.

"Society is judged by how we treat our most vulnerable," Baker said.

Baker said she believes that DOC staffing shortages are a factor in why 4-point restraints are used for so long. Her report is a part of the effort to create new laws.

"Why we're doing this, why we're getting this out there because people in facilities, the people that I work with are often people who have the least voice," Baker said. "They're forgotten about. People don't even know that the facilities they're in exist."

They hope people know now.

"Fighting for the change of laws regarding 4-point restraints in jails and prisons has given my life a lot of purpose, and it's just an honor to be part of it," Himelstieb said.

The Colorado Department of Corrections released the following statement Monday night through Public Information Officer Annie Skinner:

"Currently this bill is in draft form and CDOC is participating in the Interim Committee as a stakeholder on this topic. CDOC is charged with protecting the safety of incarcerated individuals. The use of four-point restraints is only done in a clinical setting, must be ordered by a mental health clinician, and is very closely monitored in the cases in which it needs to be utilized to protect individuals from harming themselves, DOC staff, or other inmates. These are not minor mental health issues. The four-point restraint is only used after all other lower level interventions have been unsuccessful and/or the individual is putting themselves or others at imminent risk. DOC welcomes the opportunity to participate in the Interim Committee and to examine our policies and procedures."

Photos show a 4-point restraints room in a Colorado prison

Other 9NEWS stories by Nelson Garcia :

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Latest from 9NEWS