FRISCO, Colo. — When Brian Bovaird became Summit County’s emergency manager in 2018, he was immediately met with a fundamental problem unique to mountain communities that rely on tourism.

“Our census population is about 30,000,” Bovaird said. “The busiest ski times, we have upwards of 200,000 people in the county.”

It means a challenge in alerting people about emergencies in an area prone to wildfire and potential flooding. For years Summit County relied on an opt-in alerting system called CodeRED, which automatically registers landlines, but requires anyone with a cell phone living in the county to log on to a website and create an account. The county calls its CodeRED alerting system SC Alert.

“I felt it was imperative to have a system that when we have all these visitors during busy times of the year, if there’s an emergency and we need to get information out, it’s critical that we have this system that operates on a universal basis, and not an opt-in.”

So, within his first few months on the job, Bovaird applied for the county to use IPAWS, the Integrated Public Alert and Warning System through the federal government. Having access to IPAWS allows counties access to a series of tools including the Emergency Alert System, which broadcasts messages over television and radio stations. But it also gives the county access to send Wireless Emergency Alerts.

“Everybody will commonly be familiar with those because that is the technology that Amber Alerts are sent out. So anytime you get an Amber Alert on your phone, that is using the WEA or Wireless Emergency Alert technology within the IPAWS suite of tools,” he said.

Bovaird instantly started using the system to send WEAs, a little more frequently than some of the other counties in the state. Summit County sends WEAs whenever a public protective action, like a mask mandate, is recommended or ordered.

The county has sent WEAs to warn people about fire restrictions and power outages too.

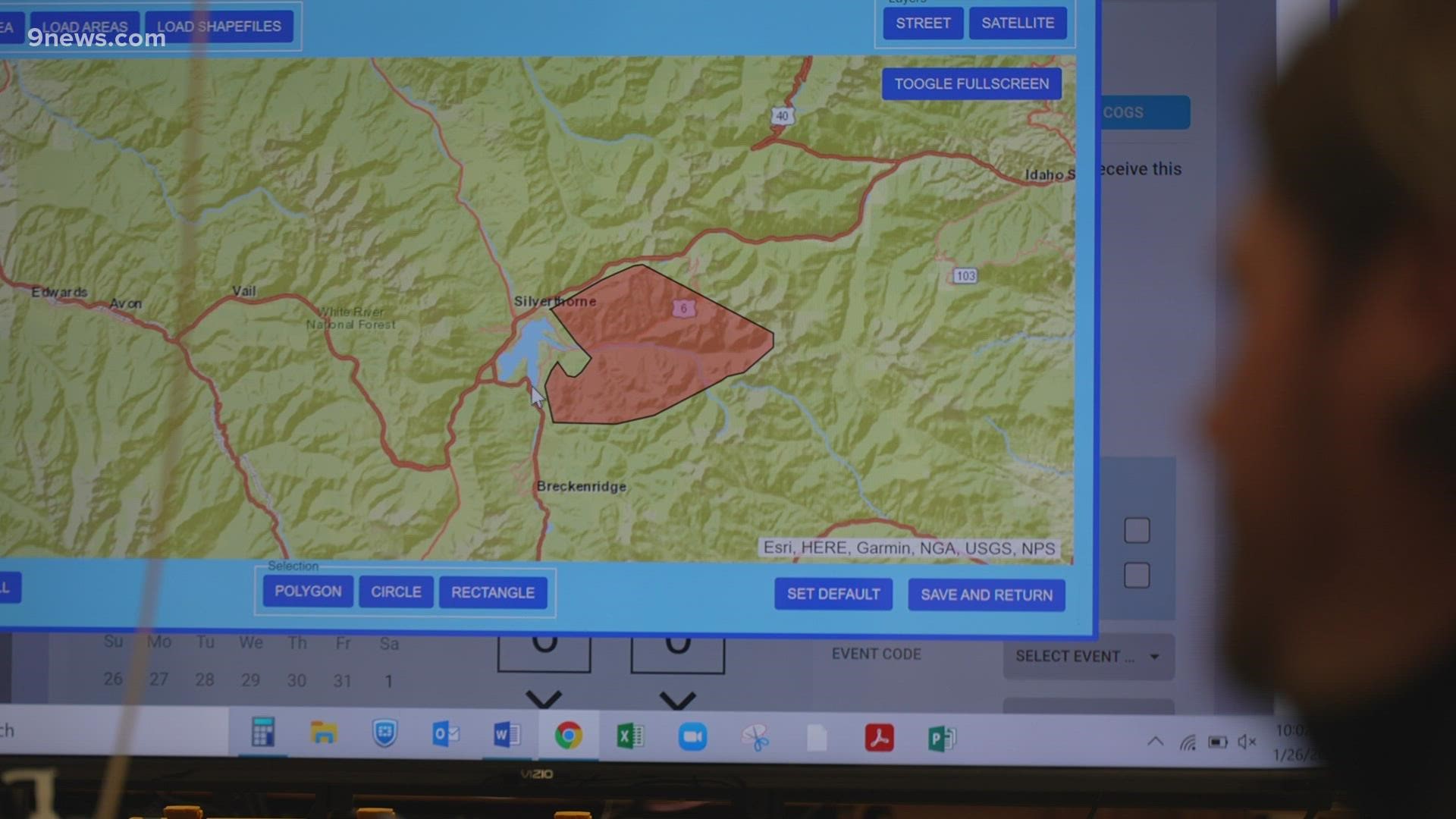

One particular summer, when Summit County was under stage 2 fire restrictions, Bovaird remembers the band String Cheese Incident did a couple of nights at the Dillon Amphitheater. Emergency managers were concerned about people camping out for the shows lighting fires at night. So they drew a polygon on the alert map, so anyone in a specific campground areas would get an alert warning them not to light a fire, while others who lived there wouldn’t.

“There’s this false understanding in general that it has to be the end of the world before you send out a wireless emergency alert and that’s just not the case,” Bovaird said.

“Here in Summit County our parameters for using IPAWS is anytime we’re ordering or recommending a public protective action – so if there’s something happening and we want the community and the individuals to take an action – that’s what we’ll use IPAWS for.”.

The use of WEA doesn’t stop the county from using its separate opt-in service for messaging. Bovaird said the county will use the service to send supplemental messaging in a disaster. For instance, if a WEA warns people to evacuate because of a wildfire. The SC Alert, sent to people who’ve opted in might give details on evacuation centers.