DENVER — Within minutes of filing a story that included video of pedestrians crossing Colfax Avenue mid-block, we got quite a few e-mails from people wondering why we were so focused on street design, rather than the people jolting across the street outside of a crosswalk.

So, let’s explore jaywalking and how it became a thing.

First, let’s look at the data. Since 2017, Denver has issued 130 jaywalking tickets, according to the Denver City Attorneys office, 34 of them since January 2021. The Aurora Police Department, which also patrols a long stretch of Colfax, has written 49 tickets related to jaywalking since January 2021.

With so few tickets written, it would appear drivers are more angry about jaywalking than police are. And there’s a deep-seeded reason for that. It has to do with the history of the law meant to keep people walking in one place on the street.

“Jaywalking used to just be walking,” said Peter Norton, an engineering professor with the University of Virginia. “And when walking got to be a complication for drivers then people who wanted to sell cars especially and auto clubs and other interest groups decided they needed to restrict some walking.”

Norton, who authored a 2007 scholarly article “Street Rivals: Jaywalking and the Invention of the Motor Age Street,” has studied the history of how jaywalking became a law. His research found the law has its roots, as many laws that govern our roads do, from auto companies.

When automobiles were a novelty on U.S. roadways, many people wanted to keep them out of cities where people walked freely in the streets. Many cities like Cincinnati considered rules that would either keep motor vehicles out of cities or govern their speeds.

“Most people were saying, look, if you want to drive, you have to drive slowly,” Norton said. “And if you won’t drive slowly, we will demand restrictions that make the car limited mechanically to a maximum speed of 25 miles per hour.”

“Those proposals were common and well supported but they also motivated people who wanted to sell cars to organize to change that debate.”

Norton said the new pro-car lobby successfully defeated the bans in cities, then banded together to push for laws that would restrict where people could walk in the street.

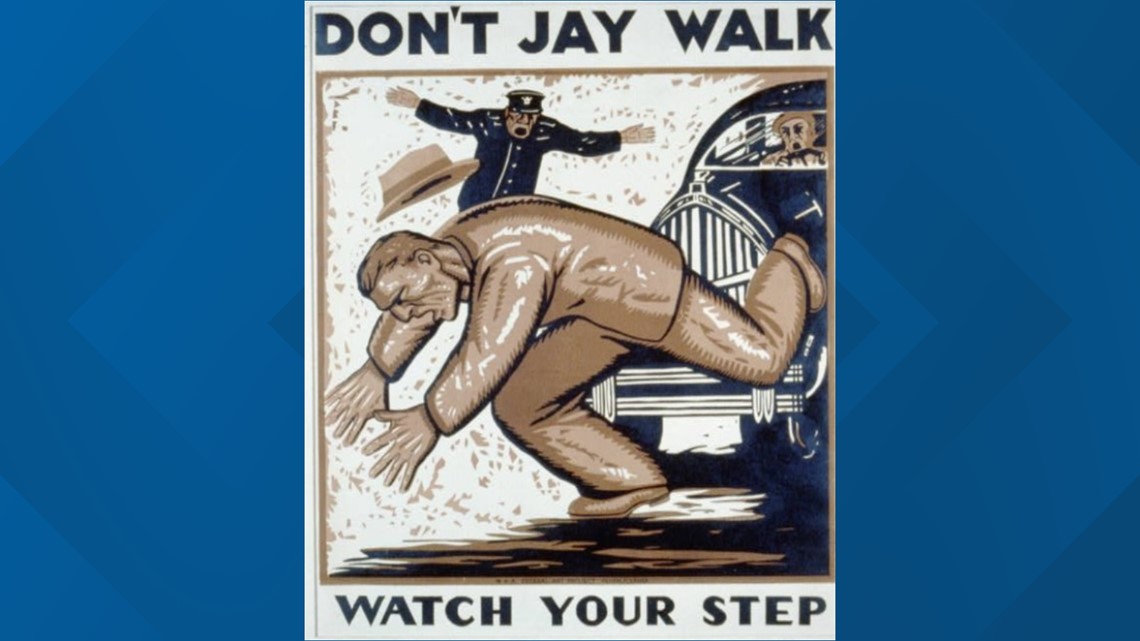

“Jaywalking started as a term of ridicule,” he said. “The term ‘jay’ meant hick. It was actually harsher than that and it was a way to sort of pressure people out of using streets the way people had always used streets before.”

“[Pro-car advocates] got together and said we need a new message. And their message was 'it’s the motor age.' It’s the 20th century. Times have changed. Get with the program. If you still think walking in streets is OK then you’re stuck in the past.”

Then, Norton says, they went from changing laws to changing norms.

“One of the techniques in the 1920s was to get into the schools and teach children – streets are for cars,” Norton said.

“We’re three or four generations into this, so we tend to grow up thinking it’s quite natural and normal and pedestrians doing anything other than crossing at the crosswalk with the signal as jaywalking.”

Jaywalking has evolved into a crime with some equity issues. A recent report from Taskforce To Reimagine Policing in Denver suggested decriminalizing jaywalking. Data that group collected and analyzed showed disparities. For instance, the group found 40% of jaywalking tickets written in the city went to Black citizens, while they represent only 10% of the city’s population, according to the report. A quarter of all tickets issued went to citizens who were homeless, transient or vagrant.

Wes Marshall, an engineering professor at the University of Colorado Denver who teaches new traffic engineers, said traffic engineers have looked at pedestrian-crashes based on fault for years.

“When that happens, we blame it on the pedestrian -- like they were jaywalking, they did something they shouldn’t have done,” Marshall said. “My thinking is we need to ask ourselves why did they do that? In a lot of the cases the intersections we built them aren’t safe.”

Pedestrians may feel unsafe in a marked intersection if they aren’t given enough time to cross or if drivers are turning against a signal. Or they may need to get somewhere but don’t want to walk a half a mile to the nearest intersection.

Norton said he once visited Denver and walked along Colfax. He remembers jaywalking specifically.

“It’s a street with a lot of nice destinations along it -- could be a very walkable place. But the fast cars do make that harder,” he said.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Full Episodes of Next with Kyle Clark