ADAMS COUNTY, Colo. — Police are required to police the police.

Colorado law now requires law enforcement officers to stop other officers from using excessive force, or report it after it happens.

Otherwise, it is a crime.

The "failure to intervene" part of the state's police accountability laws has been used to charge law enforcement officers in Loveland and Aurora, for high profile incidents.

When an attorney released video of the violent arrest of 73-year-old Karen Garner in Loveland, two officers were charged with crimes, including one for failing to intervene.

Last week, Aurora's police chief released body camera footage showing a use of force arrest that also resulted in two officers being charged with a crime, including one for failing to intervene.

But it took an open records request to find the first time the failure to intervene crime was ever charged, along with the six-figure settlement paid to the victim.

"I got up, and I looked up at the camera, and I asked them, 'does this video work?' And he told me, 'yes,'" said Michael Cassidy.

Cassidy was arrested in August 2020 on a series of charges that were ultimately dismissed.

What happened to him at the Adams County Detention Center last summer not only resulted in criminal charges against three Adams County Sheriff's Deputies, but it also led to a $300,000 settlement with the county.

"I was assaulted in jail in handcuffs," said Cassidy.

Repeated requests for the jail video showing what happened have been denied. The Adams County Sheriff's Office would not release the video. Why?

"This is a pending case that is still in the process of prosecution so the DAs office does not want the video released at this point for multiple reasons," Sgt. Adam Sherman wrote in a June email.

Since the video is not being released, we have to rely on Cassidy's play-by-play of having his hands cuffed behind his back in a locked jail cell.

"I slipped them in front of my body, and I was told after that, by the jailers, to put them back behind my body, and as I was doing that, I got jumped and beat up," said Cassidy. "I had finished putting the cuffs behind my back and they jumped on top of me."

Prosecutors with the 17th Judicial District Attorney's Office charged Deputy Andrew McCormick with assault. Almost one year later, he remains on unpaid administrative leave until an internal affairs investigation is completed. That won't happen until his court case is done, which hasn't gone to trial yet.

Deputies Chad Krause and Michael Montgomery were also charged with assault, and for the first time in the state's history, failure to intervene. They are assigned to administrative duties. According to Sherman that means they are not acting in a law enforcement capacity.

"The failure to intervene and the duty to report really came after what happened with George Floyd, specifically, because we saw so many officers standing around and doing nothing or helping out, right?" What we did was we created a failure to intervene and to report with a mind of changing culture within police departments, by saying not only will you not stand for it, you will report it," said State Rep. Leslie Herod, D-Denver.

Herod sponsored the law in 2020, with some additions passed by the lawmakers this past legislative session.

It includes a provision that video get released no later than 45 days after the allegation of misconduct.

"When things aren't transparent, when our government and our governmental entities are not transparent, it feels like they're hiding something and we have to bring that to light," said Herod.

The Weld County Sheriff's Office investigated the incident, resulting in a 72-page police report. Weld County would not provide a copy of the report because the 17th Judicial District Attorney's Office, which is prosecuting the case against the Adams County deputies, did not want it released.

In a statement, Democratic District Attorney Brian Mason wrote:

The District Attorney’s Office is committed to transparency in the criminal justice system and in our work. Our commitment to transparency must comply, however, with the legal rules of ethics and Colorado’s Rules of Professional Conduct, which govern what we are permitted to disseminate to the public when a criminal case is still pending. These rules are in place to ensure that the integrity of an investigation is upheld and that defendants have a fair trial.

"The public dissemination of certain pieces of evidence and information prior to trial can jeopardize the key obligations the office and its prosecutors must maintain. Any suggestion or insinuation that the 17th Judicial District Attorney’s Office is hiding information related to this case is simply untrue. This office charged and is actively prosecuting three law enforcement officers for this alleged crime, and we will continue to see the case through to its conclusion. When it is appropriate and ethical to do so, evidence and additional information related to this case will be publicly disseminated upon request."

"While the video is not public, it was public to me. I saw it, and so did the county," said Cassidy's attorney John Holland. "If I'd filed suit, I would have had to file suit without the video, then I would have gotten the video. We would have gotten the video then, and then we probably would have held a press conference."

Holland watched the video; he just did not get a copy. Then again, he did not need a copy to get the six-figure settlement.

"How come I don't have the video? I demanded the video and I was refused the video by the District Attorney's Office, by the County Attorney's Office, by the Adams County Sheriff's Department, and I settled the case without a judicial filing," said Holland.

About the $300,000 settlement.

The Adams County Commission paid Cassidy $300,000 as a result of what happened in the Adams County Detention Center. You would not know about it because it was never voted on publicly.

At a December commission meeting, the commissioners agreed to go into private executive session to authorize the county attorney to negotiate a settlement with Cassidy.

It was never brought up again.

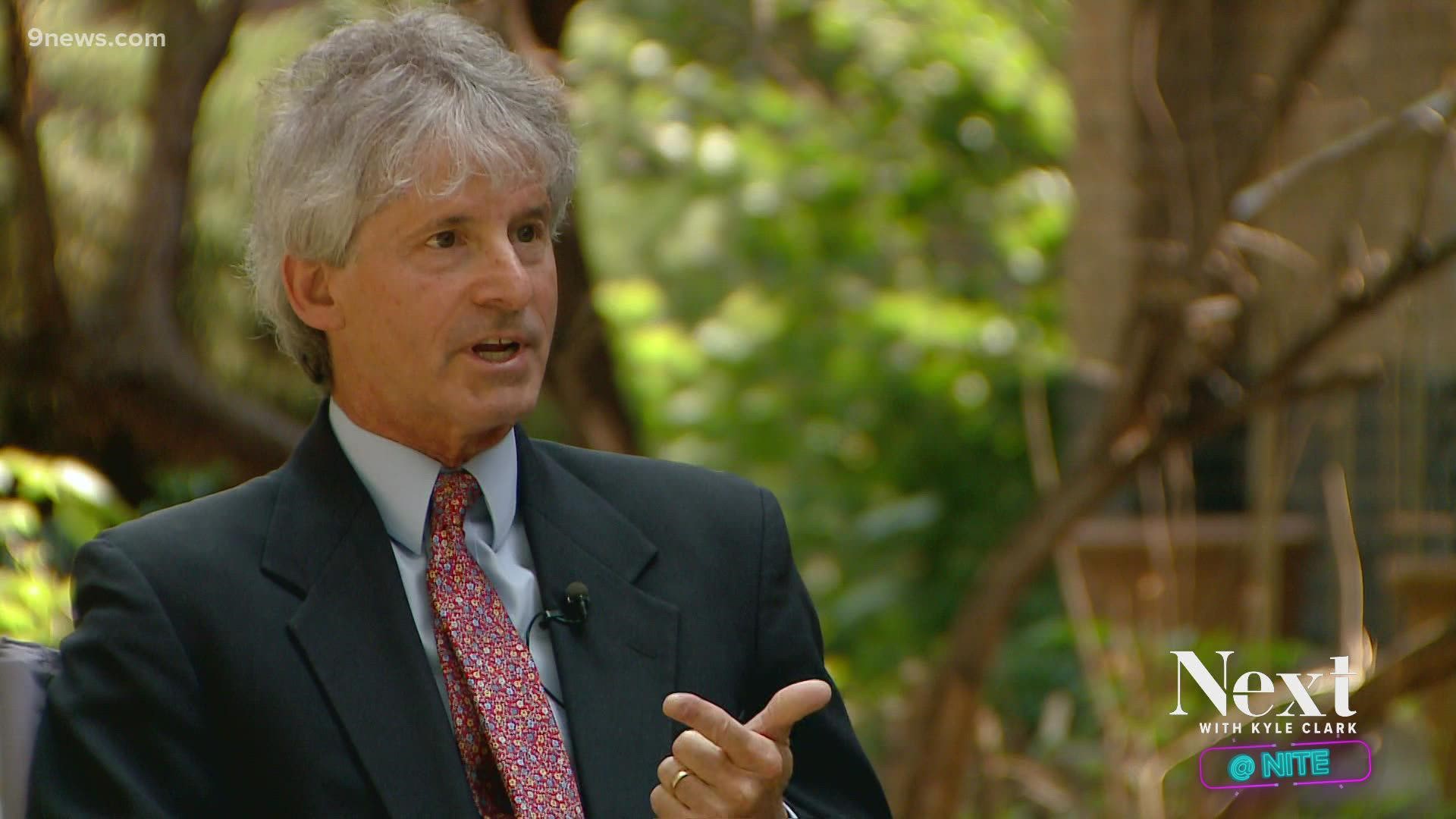

First Amendment attorney Steve Zansberg believes that violates Colorado law.

"I believe that it's perfectly acceptable for county commissioners to authorize a negotiator for an amount they're willing to settle a case for behind closed doors, in executive session," said Zansberg. "Once the settlement has been negotiated and the claimant accepts it, then it's incumbent upon the county commissioners to have a public meeting and to let the public know how much money in taxpayer funds are being spent, and who voted to approve it and who voted against it."

"Each taxpayer should know how much their city or jurisdiction is paying in these unlawful use of force cases, and we should also be able to see the video so we can make a determination, if we can, about if someone stepped across the line," said Herod.

Put the settlement aside for a moment. Cassidy was in jail. He was in handcuffs. Why should it matter what happens behind the barbed wire fencing of a jail?

"There needs to be some accountability," said Cassidy. "The jail is still in the United States of America, and the laws do apply to them."

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Full Episodes of Next with Kyle Clark