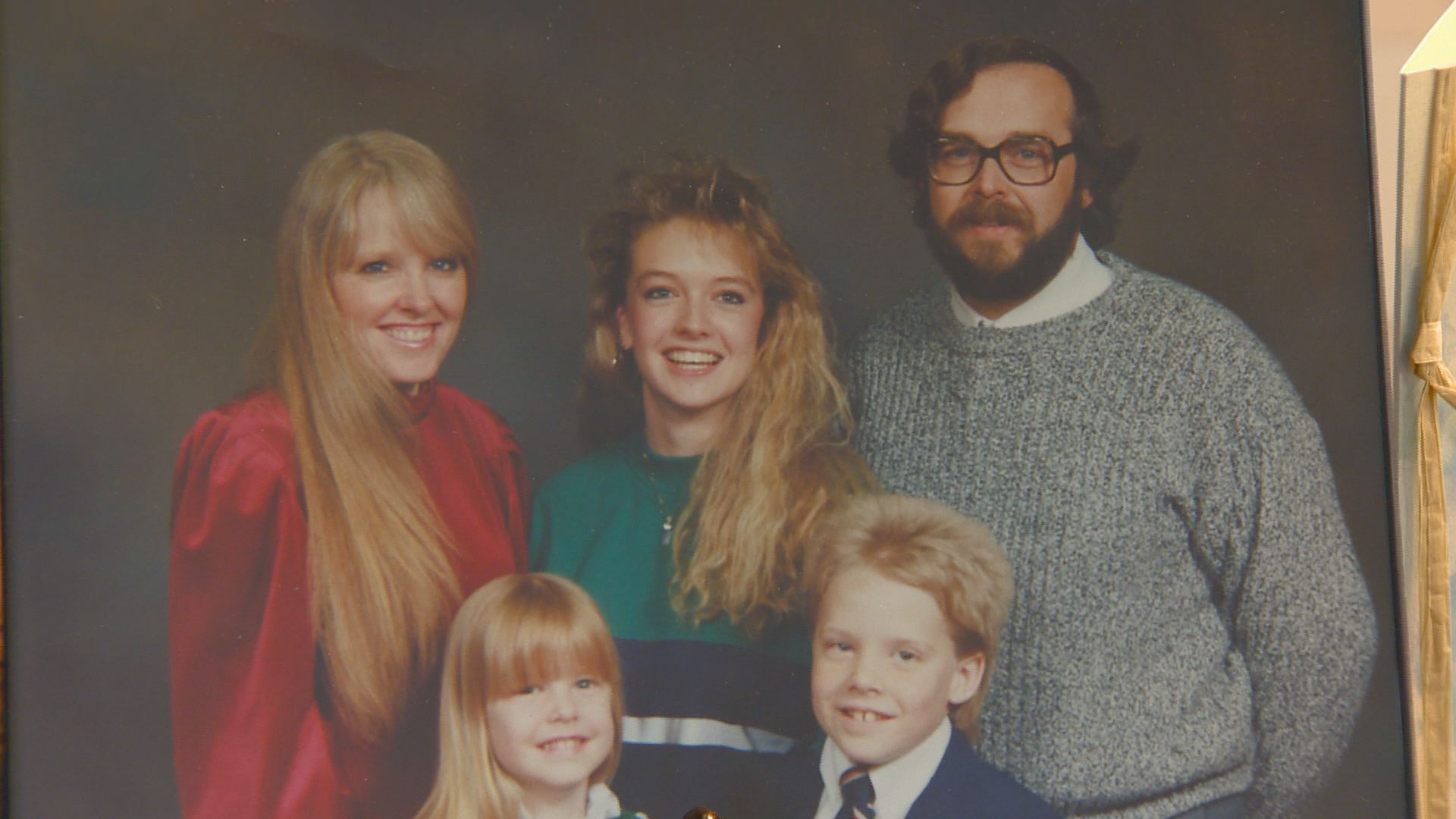

AURORA, Colo. — Herb Myers first met his wife Kathy when they were about 3-years-old. They went to grade school and high school together, but it would still be years before Herb had the courage to ask for a date.

“About four or five years after high school we met again. I asked her out. Well, I didn’t ask her out then,” he laughs. “I just kind of got my courage up a few days later, and then asked her out.”

Herb didn’t expect that after 38 years of marriage, he’d help his wife die peacefully in their home.

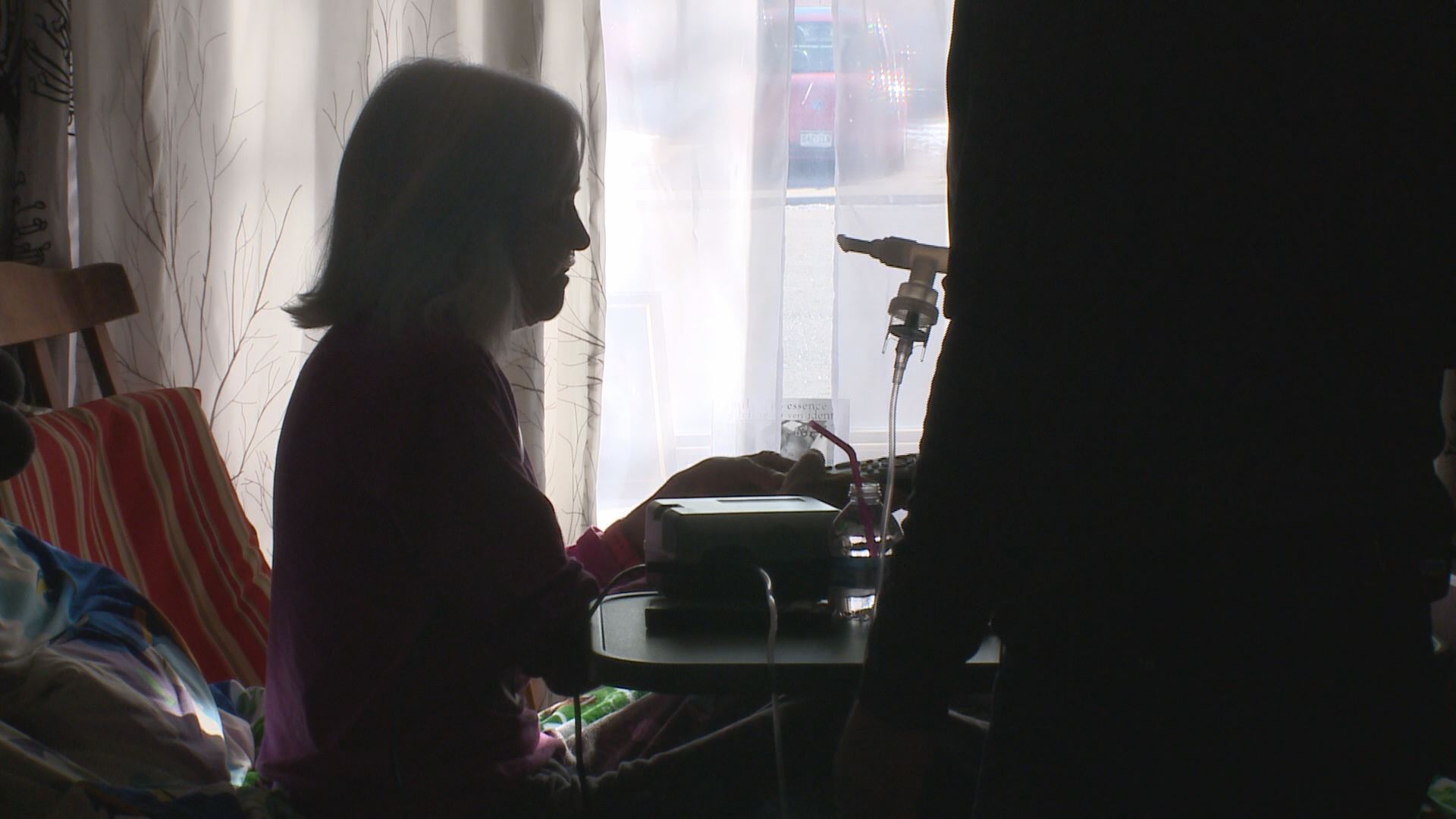

Kathy, who started smoking when she was 12, was diagnosed with COPD a decade ago. Her condition worsened as time went on, and she spent the last three years with an oxygen tank. Kathy’s last eight months were spent on Hospice care.

Back in December, after Colorado formally legalized physician-assisted suicide, Kathy and her husband immediately began the search for the prescription that would end her life. Next met them in January. They couldn’t find a doctor to prescribe the medication then. A doctor reached out to the couple after seeing our story.

On Sunday, Kathy took the medication that ended her life. Hers is the first assisted-suicide we've heard of in Colorado since the law went into effect.

“During the day, I can keep busy, so I’m okay. At night, once it starts getting dark, it’s like the whole world kind of closes in a little bit, and that’s when I miss her the most,” Herb says, choking back tears.

Kathy wasn’t sure if she’d take the prescription that took months to get her hands on, when Next last spoke to her. She felt a sense of relief knowing she had the option. Kathy decided it was time a week before her death.

“I didn’t think she was quite serious… I don’t know. Maybe that was my own not wanting her to leave yet,” Herb says.

She planned to do it last Sunday, after making it through her daughter’s birthday, her husband’s birthday and their wedding anniversary in the first few months of the year. Sunday was the day before Kathy’s own 63rd birthday.

Herb didn’t give Kathy any pain medication that day, to ensure she was of a sound mind when she took the life-ending prescription – 100 gel capsules, each needing to be broken and emptied, and the contents mixed with a sweet drink to drown out the bitter taste.

“My hands were shaking and I had a knot in my stomach. It took me about an hour-and-a-half. That’s the only thing I really regret, that I hadn’t done it earlier. But I didn’t know if there was a shelf life to it after I mixed it. I missed out on an hour-and-a-half of time that I could have been with her just before the end,” Herb says, again holding back tears.

Once he finished, he set the drink on a tray next to Kathy’s hospital bed. Herb says she drank it all, quickly. Kathy was surrounded by Herb, their daughter and her husband, and their Hospice nurse, who asked to be there in case something went wrong, and to learn more about the process.

“We held hands. She laid back on her pillow, and within about two minutes, her grip on my hand let up. And I looked up, and I never saw her take another breath,” Herb says. “It was very quick ... very gentle.”

The nurse measured Kathy’s vital signs after 30 minutes, and there were none.

Herb, who watched his brother die slowly of AIDS in the 90s, hopes more doctors will begin prescribing physician-assisted suicide. He wants the process to become easier for patients and their families.

“The doctors stepped out of their comfort zone, and I thank them very much. But people shouldn’t have to die like my brother did… you should be able to just lie back on your pillow and have it done. That’s what I hope comes of all this.”

While Kathy is the first that we know of, it is possible that other families in Colorado have gone through this process privately. Next year we'll learn how many prescriptions were written, and how many were filled, but not how many people took them. That information remains private.

Death certificates will list the cause of death as the person's terminal illness, not physician-assisted suicide.