DENVER — Overdose deaths in Colorado are ripping families apart. In some cases, children are losing their mothers before they even turn 1, which is why Swedish Medical Center in Englewood is trying out a new program they hope will save new parents.

Jennifer Richardson, the director of women services at Swedish, said nurses and doctors are seeing expecting moms and parents come in every week with substance use issues. They also treat a handful of babies in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit going through withdrawal every month.

She said that for a long time, there was a feeling of helplessness.

"Maybe give a couple of phone numbers," Richardson said of staff trying to find solutions. "We're with them for such a short amount of time, sending them back into the community with nothing."

"We're seeing more of our patients with substance use disorder," she said.

It's to the point that overdose is one of the leading causes of death when it comes to maternal mortality.

"What we are seeing is, reflected in the maternal data, is a part of a larger national trend for overdoses," said Dr. Don Stader. "It's consistently climbing the rankings as a cause of death among Americans, especially young Americans."

"Suicide and overdose kind of flip-flop depending on the year," Stader said about about maternal mortality.

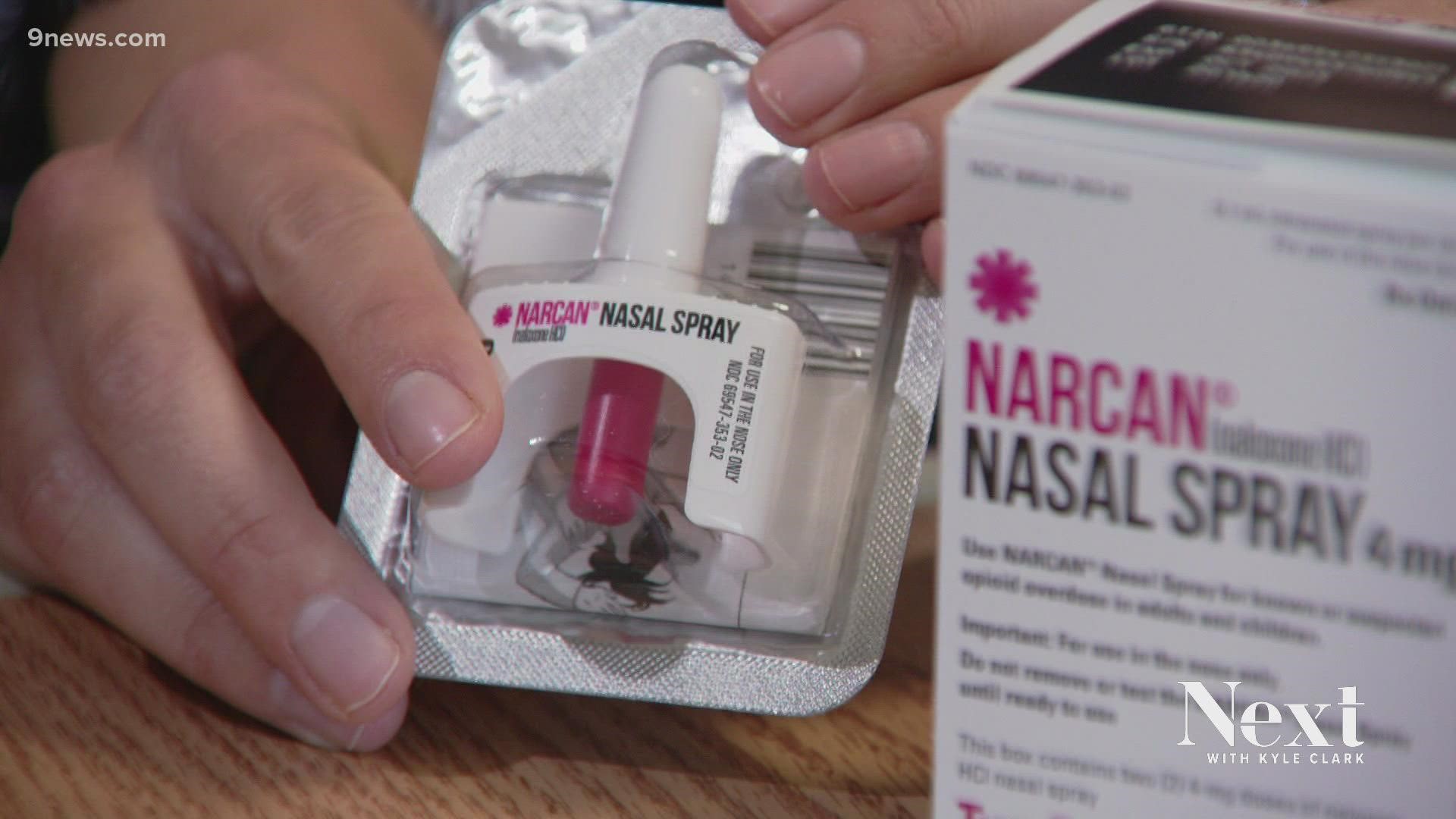

Stader helped launch a pilot program offering naloxone, which can help reverse an overdose, in emergency room departments at Swedish.

He said that program has now expanded to labor and delivery at Swedish. He said when patients are screened for substance use disorder, if health care providers deem it necessary, they will put naloxone in their hands before they leave the hospital.

"Most moms are lost after delivery … with addiction they often cut back drug use during their pregnancy because they don't want to affect the infant," Stader said.

But after the baby is born, they may relapse, their tolerance level will be lower, and they can overdose.

The pilot program launched at Swedish on Aug. 31 with plans to launch at a Colorado Springs hospital later this month.

At Swedish, the goal is to get the naloxone kits into as many as 10 families a month.

There is also training for staff to help navigate stigma, which is magnified when an expecting parent also needs help with drug use.

"There's a fear," said Richardson. "If they are honest, why are we asking these questions, or how they answer, that there are going to be some consequences. That's where training for nurses come in, to come from an honest perspective. We are not here to judge but to make sure you understand the process."

"For someone's family members we are not obligated to report that," said Richardson about mandatory reporting to the state. "For patients, if someone does test positive for using a substance, they are delivering, we are obligated by the state to involve Child Protective Services. That service takes over and determines -- comes to the hospital to meet with the family to discuss what the next steps look like."

Stader said there are also scenarios where they can ask more open-ended questions that can justify sending naloxone home not just for new parents, but anyone in the family who may need it.

He said this is also an area they are navigating to figure out best practices and experimenting with what will work best.

He also said it's important to strike the right balance between helping new parents and making sure newborns are kept safe.

A baby going through withdrawal can be jittery and inconsolable. Swedish had volunteers who come in to cuddle and sooth babies.

Stader said babies can be born dependent on opioids but not addicted. He said addiction can't happen until a person has a mature brain and addiction behaviors manifest.

The program is funded through a $500,000 grant from the state.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Full Episodes of Next with Kyle Clark