DENVER — The repeal of Colorado's death penalty will get another hearing at the Colorado state capitol on Tuesday.

The bill, which passed out of the state Senate, goes through the same process in the House, starting with a committee hearing Tuesday afternoon.

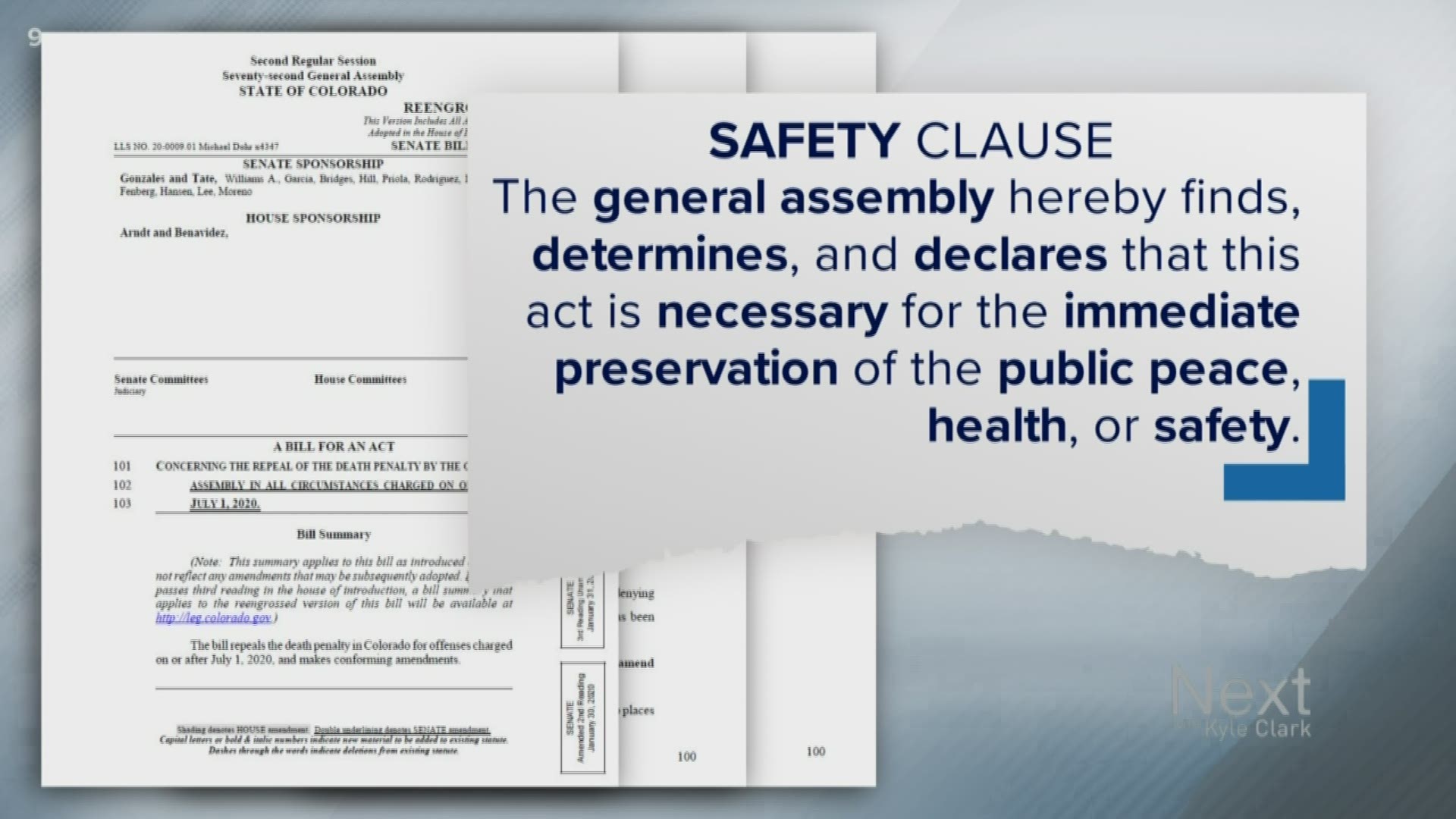

When it passes out of the House, which it will, it will pass with a safety clause included.

The safety clause is a section at the end of the bill that makes the legislation take effect immediately (or upon the date listed in the bill), without challenge from the general public.

"Safety clause: The general assembly hereby finds, determines, and declares that this act is necessary for the immediate preservation of the public peace, health, or safety."

For the safety of whom?

"Of the people potentially charged with the death sentence," said Rep. Jeni James Arndt, D-Ft. Collins.

Arndt is one of the House sponsors of the bill that would do away with the death penalty as an option for prosecutors for crimes committed after July 1, 2020.

If it didn't have a safety clause, the public would be given 90 days from the end of the legislative session to collect more than 124,000 signatures to try to put this to a vote of the people.

"District Attorneys don't go to a vote of the people to make the decision on whether to charge the individual with first-degree murder or a death penalty-eligible first-degree murder case," said Sen. Julie Gonzales, D-Denver, the Senate sponsor of the bill. "Having a petition clause doesn't stop voters from the state of Colorado from going to the ballot.

She's right.

Any legislation can be challenged by voters, it's just harder when there is a safety clause. If someone wanted to try to bring back the death penalty if the legislature repeals it, they would have to go through the process at the Secretary of State's Office to draft a title for a ballot issue, get it approved and go through the approval needed before they could start collecting signatures. Bills without safety clauses just make that process easier.

Bills like the National Popular Vote, which Arndt also co-sponsored last year.

"We did not put a safety clause on the National Popular Vote for that very reason. It didn’t fit the definition of a safety clause, it had nothing to do with the public health and safety and immediacy," said Arndt.

The National Popular vote is the law that Colorado passed that would tie our electoral college votes to the presidential candidate that gets the most votes nationwide, not just in Colorado. It can only take effect if enough states agree that would give the nationwide winner more than 270 electoral college votes.

After that bill passed, people started gathering signatures to try to overturn it at the ballot. They needed 124,632. They turned in more than 183,000 valid signatures.

"I was not upset about that because it was people taking action to govern themselves," said Arndt.

Based on research done by Colorado's legislative legal services, Colorado's Senate first used the safety clause in 1913, when it wanted to create an eight-hour workday for coal miners, but did not want the public to stop the decision.

The safety clause was a standard for bills from the 1930s until a 1997 memo by legislative leadership reversing the trend and requiring lawmakers to request a safety clause.

Current lawmakers must think Colorado is rather unsafe. Nearly half of all bills in the last three years have come with a safety clause.

- 2019: 46% of 460 bills

- 2018: 44% of 432 bills

- 2017: 45% of 423 bills

RELATED: Colorado legislature seeks to eliminate time changes by implementing year-round daylight saving time

SUGGESTED VIDEOS | Full Episodes of Next with Kyle Clark