KUSA — An Arvada home for adults with disabilities where three people died in a 2016 fire was a firefighter’s nightmare of blocked exits, missing smoke alarms and barred windows, a 9Wants to Know investigation found.

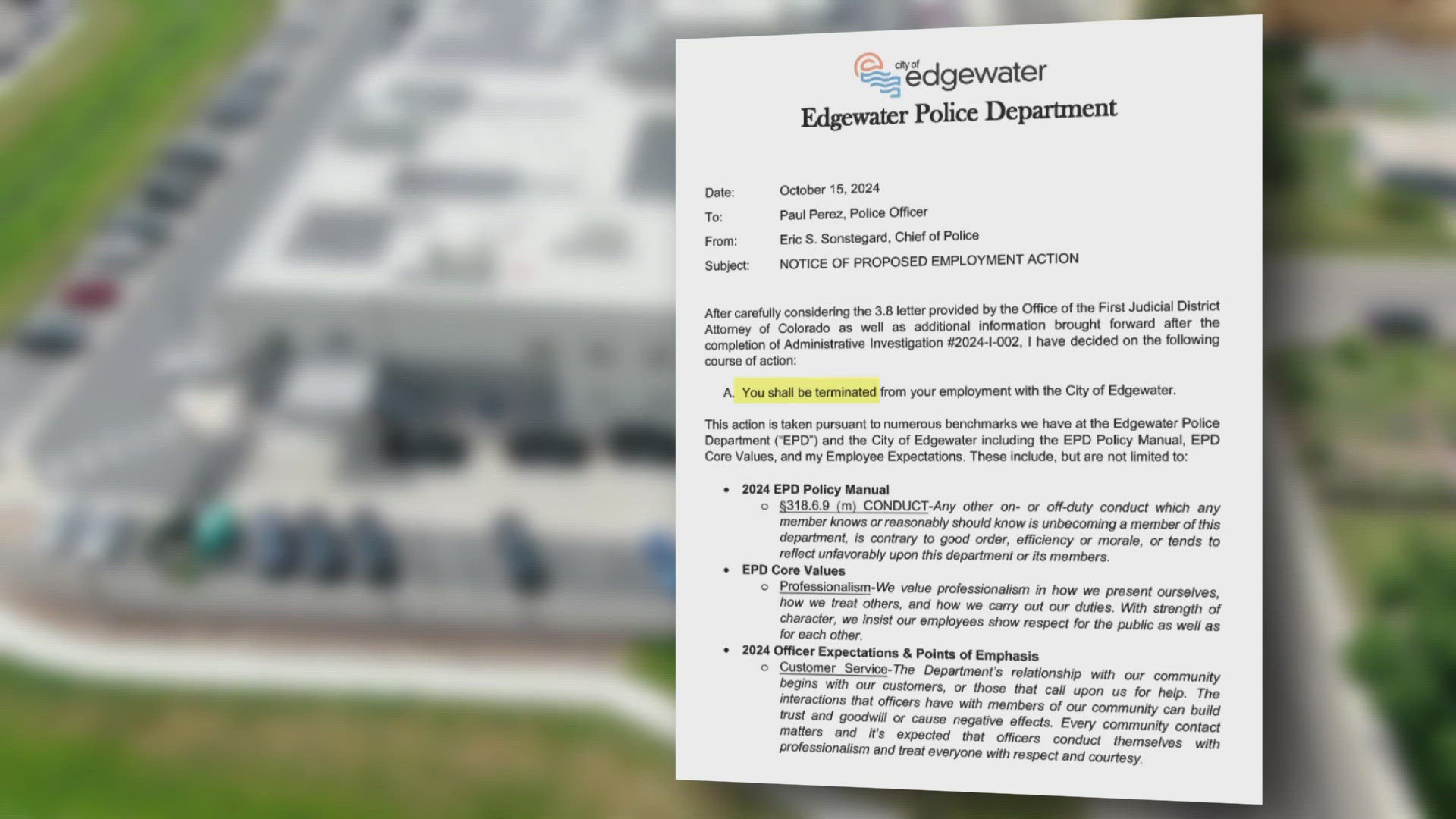

But because the structure was designated as a “host home” – where as many as three adults with disabilities can live with their caregivers – Colorado law doesn’t require that it be subjected to fire inspections or impose other rigorous fire-safety standards, such as alarm systems. It’s meant to be treated like a single family home – not an institution.

What firefighters encountered at 6152 Robb St. early the morning of May 14, 2016, were numerous hazards that made it difficult for people inside the burning structure to escape and for help to get in, 9NEWS found.

Hundreds of investigative photographs and police and fire reports – and videotaped interviews with the two women blamed for causing the fire – lay out the obstacles in stark detail.

One exit door – just a few steps from the place where two people suffered the injuries that killed them – was deadbolted shut – and no one could pinpoint afterward where the key was. Firefighters broke in a door from the backyard to the kitchen, only to find their path blocked by an upright freezer. A window in one bedroom was blocked by a table piled with clutter, and bars covered several basement windows.

Smoke alarms were missing in the basement. A fire extinguisher hadn’t been inspected in nearly two years.

The home had previously been a “group home” – where Colorado law allows four or more disabled people to live and where a fire alarm system is required. Sometime after the structure was reclassified as a host home, that alarm system was disabled, according to Arvada Fire Marshal Kevin Ferry.

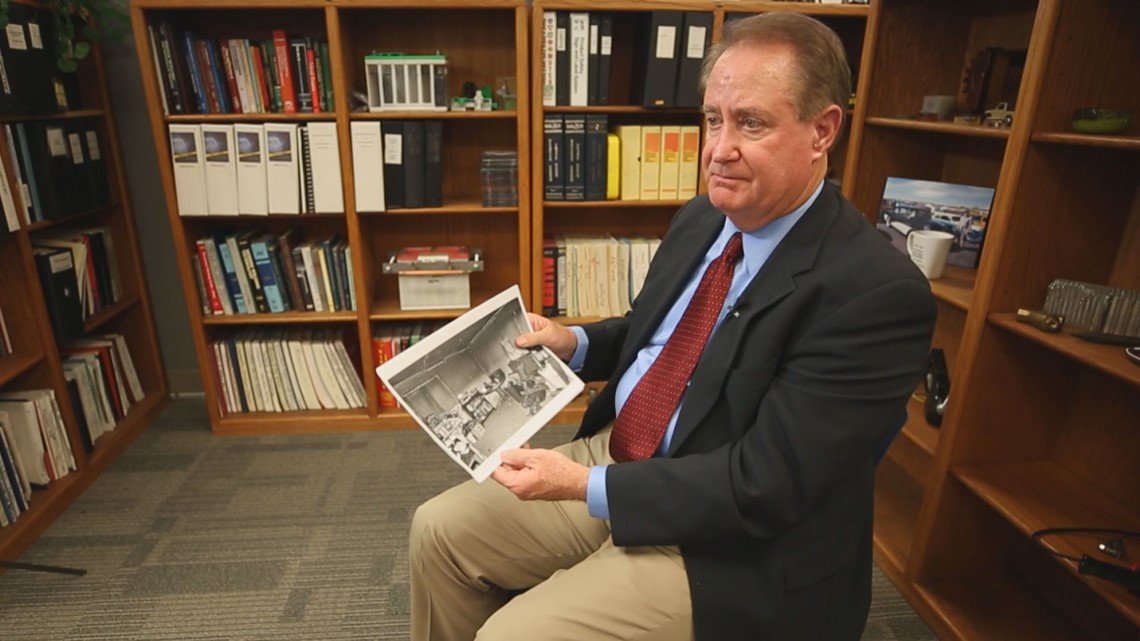

“Clearly this is a case of, if proper fire code enforcement had been in place or utilized, I truly believe we would not have three dead individuals in this case,” said Pat Andler of Phoenix, a nationally known fire investigator.

Andler, who has investigated an estimated 2,500 house fires, reviewed hundreds of pages of reports, photographs and other evidence obtained by 9Wants to Know.

He used words like “absurd,” “not acceptable,” and “not the answer” in reacting to the conditions in the home.

At the time of the fire, the home was owned by Scott Parker and was operated by his company, Parker Personal Care Homes. He declined 9NEWS’ requests for an interview and declined to answer specific written questions. Instead, he issued a statement, reading, in part:

Because it was a single family home and not a group home, there were no legal requirements to provide fire alarm/monitoring systems or to allow outside fire inspections.

Host home providers are required to comply with local, state and federal rules and regulations, as well as PPCH policies. Providers are required to conduct regular fire drills and ensure that all smoke detectors and fire extinguishers in the home are functional. PPCH provides care providers with training and its supervisors regularly monitor host home for compliance and overall safety. PPCH would not have tolerated any known unsafe or non-compliant conditions or practices.

After 9Wants to Know again asked him to address specific issues in the home, Parker issued a second statement:

Our entire organization was devastated by the tragic incident in 2016. Nothing is more important than the health and safety of our clients, and we remain committed to providing rigorous monitoring of all our homes to ensure compliance with all applicable regulations and the overall safety of the clients. Among other things, our “safety-first” culture includes the training of caregivers regarding emergencies of various types and requires that all host homes feature functional fire extinguishers, smoke alarms and evacuation drills.

When the fire broke out, there were six people in the home:

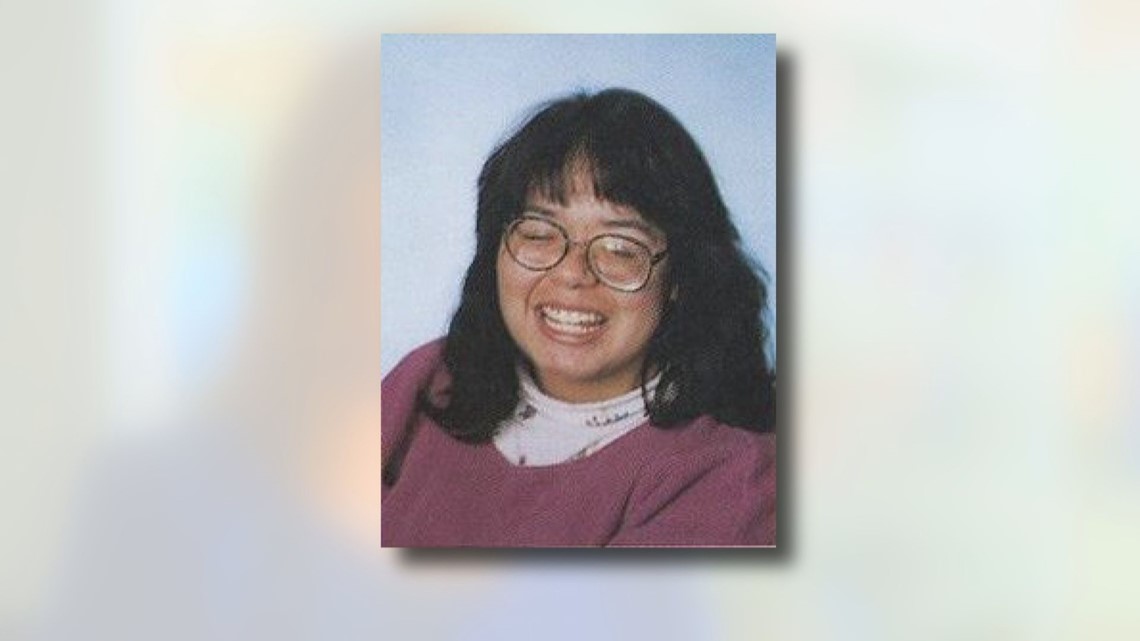

- Tanya Bell, a 39-year old woman with cerebral palsy and intellectual disabilities who used a wheelchair. She was in her bedroom, which had been built in the garage of the 1961 ranch home.

- Arthur, a 34-year-old man with autism, was in his bedroom at the opposite end of the home.

- Mary “Liz” Turner, the caregiver at the home, was in her basement bedroom with her partner, Shana “Dee” Moore, who was an employee of Parker Personal Care Homes.

- Moore’s daughter, Cristina Covington, 23, and Covington’s 4-year-old daughter, Marielle, were in a main floor bedroom across from Arthur’s room.

- Moore’s 16-year-old son, Max, was in his basement bedroom.

Bell, the only person in the home to call 911, was found slumped in her wheelchair and died a short time later at a hospital. Marielle also died early that morning at a hospital, and Covington died a week later, succumbing to the effects of breathing toxic, super-heated smoke.

Arthur suffered serious injuries. Moore fell out a window trying to pull Arthur to safety.

Security bars mounted into the foundation prevented Turner, along with Moore’s son, from getting out of a basement window. They went to another room and were able to climb through a window.

The fire apparently began hours earlier, after Turner and Moore had gone out onto the front porch of the home to smoke cigarettes. They both later told investigators that they put them out. Moore told investigators they placed the butts in an ashtray, but Turner said she put them in an empty cigarette box, and eventually set that inside a small wicker table on the front porch.

Investigators later concluded the cigarettes weren’t out, and they smoldered for a time before erupting in flames, burning up the outside wall – which was next to Bell’s bedroom – and entered the home.

Tanya Bell called 911 shortly before 1:30 a.m.

“It’s six-one-five-two Robb Street,” she said after being asked the address of the emergency. “And there’s a fire in the front yard. On the front porch.”

Bell spent nearly four minutes speaking to dispatchers – her last word was a panicked “hurry” – before apparently losing consciousness in the stifling smoke.

In the meantime, Turner awoke in the basement bedroom she shared with Moore to “all this banging and crashing,” she told police and fire investigators.

Her first thought: That Arthur was up, maybe sleepwalking, maybe bumping into things. She noticed the baby monitor in the room – her lifeline to Tanya – vibrating continuously and reached for it to turn up the volume. That’s when the power went out.

She smelled smoke and awoke Moore.

“Dee and I ran up the stairs,” Turner said in her videotaped interview. “And as soon as she opened the door – I was literally like three steps behind her – when she opened the door smoke just started flowing in in our face, and she screamed, ‘There’s a fire – get everyone out.’”

Turner retreated to the basement to awaken Moore’s son. When she went back up the stairs, the flames stopped her, and she and Moore’s son retreated to the basement, broke out one window, found their path blocked by bars, and went to a different room. They escaped through a window.

In the meantime, Moore rushed down the main floor hallway toward her daughter, granddaughter and Arthur.

“It was just, like, bright orange,” she told investigators. “It was like all over the front of the – the front of the – where the door is, the front door. And the smoke was black and it was – like it was getting thicker. And so I just remember when I was coming out into the hallway, it was getting in the room so quick, so it was just black and thick and I just started coughing.”

She found her daughter and granddaughter, and they followed her into Arthur’s room.

They then dragged him back across the hall and was trying to pull him out a window when she fell to the ground and was stopped from going back in by a police officer.

Along the way, in the confusion and the smoke, Cristina Covington and Marielle ended up in the bathroom in Arthur’s bedroom, just a few feet from the deadbolted door that led to the backyard and fresh air.

Afterward, as police and fire investigators tried to sort out what happened, they focused, in part, on that door out of Arthur’s bedroom.

“Do you guys have the key for that, or anything?” Arvada police Det. Trevor Hettinger asked Moore in videotaped interviews obtained by 9Wants to Know.

“No,” she replied.

“You don’t have a key for that?” Hettinger asked again.

“No,” she answered again. “Not that I’m aware of.”

The investigator asked Turner the same question.

“I think there’s a key on keyring,” she answered. “Um, it was either on the keyring that was hanging on the front door that had the key to that deadbolt, or it was a key in the cabinet above the stove.”

The door was deadbolted to keep Arthur from being able to wander off.

ORIGINAL STORY: 3 dead after fire at home for the disabled

When Hettinger interviewed Parker, the owner and operator of the group home, he brought up the same subject – referring to it as the door “that you essentially couldn’t open it.”

“That is – I was not aware of that,” Parker answered.

He also said he was not sure why there would have been a freezer blocking the door out of the kitchen into the backyard.

“I don’t know why that would be …,” Parker said. “Because there's three back doors to that house. There’s great big sliding doors in that little family room area. There’s the back door from the kitchen. And then there was Arthur’s door out that back bedroom.”

Andler, the Phoenix fire investigator, was critical of the conditions in the home – and Colorado law.

“Hosts receive money to provide protection and safety for disabled individuals,” Andler said. “They have a responsibility to take care of these individuals. … There's a need to protect them, and if we don't provide their protection this is exactly what happens, and that is three dead bodies.”

Arvada Fire Marshal Kevin Ferry said that had someone from his department been in that home just before the fire, the residents would have been counseled on all of those issues.

“A lot of times we go into homes we find all these things,” he said. “The double-key deadbolt with no key in it? Not a good idea. Not very safe. A refrigerator blocking a way out of a house? Yeah, I wouldn't put it refrigerator in front of a door. Should you keep windows clear so that it can be accessible? Yes. It’s helpful and it could make a difference.”

Chapter 2

%

Colorado law leaves the care of adults with disabilities who live in small community “host homes” to multiple state and private agencies – but gives local fire departments no power to make sure they’re safe, a 9Wants to Know investigation found.

The homes, where as many as three adults with disabilities live with their caregivers, are not licensed by the state and not subject to rigorous fire-safety requirements – local firefighters often don’t know where they are, don’t have the power to inspect them, and don’t have the power to order changes even if they know of problems.

The operators aren’t required to install sprinkler or alarm systems.

When a fire broke out at an Arvada host home on May 14, 2016, taking the lives of three people, responding firefighters encountered a number of hazards that may have played a role in the tragedy, the 9NEWS investigation found.

A bedroom door secured with a double-key deadbolt lock – and no one knew where the key was. A door out of the kitchen blocked by a standup freezer. A window in the bedroom where a woman with disabilities lived blocked by a table piled with clutter. Basement windows covered by bars. Missing smoke alarms. A fire extinguisher that hadn’t been inspected in nearly two years.

All of it spelled out in hundreds of photographs and investigative reports from the Arvada Fire Protection District and Arvada Police Department obtained by 9Wants to Know under Colorado’s open records laws.

The early morning fire killed Tanya Bell, a 39-year-old woman with cerebral palsy and other disabilities, and a young mother and daughter, Cristina Covington, 23, and Marielle Covington, 4.

Investigators concluded that the fire was caused by smoldering cigarettes, left behind by Liz Turner, the caregiver in the home, and her partner, Shana Moore, after they’d gone to the front porch for a smoke before heading to bed.

Cristina and Marielle Covington were Moore’s daughter and granddaughter and were staying at the home temporarily. The home’s other client, a 34-year-old man with autism, suffered serious injuries in the fire.

A grand jury indicted Turner and Moore on multiple felony charges. In a deal with prosecutors, Turner pleaded guilty to criminally negligent homicide, negligent death of an at-risk adult, negligent child abuse causing death, and negligent injury to an at-risk adult; Moore pleaded guilty to negligent death of an at-risk adult and negligent injury to an at-risk adult.

Each woman entered a two-year diversion program which, if successfully completed, will see the charges dismissed.

But while fire inspectors cringed at the conditions in the home that made it difficult for those inside to escape – Cristina and Marielle Covington were found just steps from that deadbolted door, for example – there is little in the law that could have prevented it, 9Wants to Know found.

The reason: Host homes are designed to allow people with disabilities to live in a residential setting rather than an institution.

And that means that while there are requirements for smoke detectors and fire extinguishers, fire safety is left up to local fire codes. In this case, the Robb Street home was classified just like a single family home.

“Under those regulations,” Arvada Fire Marshal Kevin Ferry said, “there is no mandated life safety regulations.”

There is no requirement for alarm systems, fire sprinklers, or annual fire inspections in host homes.

The home at 6152 Robb St. was originally built in 1961.

%

In 1992 it was converted to a group home, where at least four people with disabilities can live. Group homes are licensed by the state and are subject to fire safety rules that go far beyond what’s expected in a single-family home. They have to be inspected regularly by the local fire department and have to have sophisticated fire alarm systems.

For years, Arvada fire inspectors checked the home annually. That continued even after Scott Parker, owner of Parker Personal Care Homes, bought the house in 2002 and converted it to a host home. Host homes typically have one or two residents – but can have as many as three in certain circumstances.

Even though the inspections were no longer required, firefighters kept going to the Robb Street home every year.

In 2013, an inspector went again – and got a different reception.

“He was met by the operator of the facility, who kindly reminded us that he didn't need to comply with fire code regulations, and that we had no authority to inspect,” Ferry said. “But he allowed us to do a walk through of the facility.”

During that walkthrough, the inspector, Rich Tenorio, pointed out that the fire alarm system, left behind from its days as a group home, was not working.

“He was aware that he had a fire alarm system and it wasn't operational and he informed us that he wasn't required to have an operational fire alarm because he was a host – he was operating a host home,” Ferry said.

Both Ferry and Tenorio told 9NEWS the person who met them was Scott Parker. Parker declined to answer 9NEWS’ questions about that interaction.

In a statement issued to 9NEWS, Parker said that the home was complying with all applicable rules.

But the rules for host homes are, by design, not terribly restrictive. The reason: Host homes are supposed to feel like a home, not an institution.

“They provide an alternative living opportunity for individuals to live in the community as opposed to in an institutional setting,” said Gretchen Hammer, Colorado’s Medicaid director. “Again, we think of these not as facilities but as community-based homes in which people can live, just like you or I live in a community home.”

Hammer acknowledged that nobody from the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy and Financing had inspected the home. Neither had anybody with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, another of the agencies responsible for part of the oversight of host homes. Also in the picture are Community Center Boards, which manage the care of people like the clients in the Robb Street home, and what are called Program Approved Service Agencies, or PASAs. In this case, the PASA was Parker Personal Care Homes.

Hammer said it is up to the community boards, case managers, and PASAs to make sure a host home is safe.

“It is our expectation that both the community center board as well as that agency are responsible for the safety and the well-being of the individual while receiving services from them,” Hammer said.

The state, she said, works with those other agencies “to ensure that they're doing the proper monitoring of the individuals who are receiving services, that the service plan is up to date, that visits have been made to that individual to check on the environment in which they're living, make sure it's not too restrictive and certainly make sure it's not unsafe.”

Maureen Welch, the mother of a 10-year-old with Down Syndrome who has devoted her life to advocating for people with disabilities, first heard about the Robb Street fire in news reports. Soon she was attending court hearings for the women accused of starting the fire and asking questions of various officials involved in the complex system that provides care to people like the Robb House clients.

“I had been having concerns about the host homes in general because of the safety parameters in the different rules and regulations that vary from fire district to fire district,” she said. “There is no one level of expectation across the state of Colorado for very vulnerable and often physically impacted individuals. When we're talking about life safety, it's concerning to me.”

She questioned the safety in host homes – of which there may be upwards of 2,000 in Colorado, although no one with the state could provide an accurate count because they aren’t licensed.

“The question is are they really safe?” Welch asked. “Is this a safe environment to put these individuals in? And should the state be raising the bar?”

In her mind, the answer is a resounding “yes.”

And she may have an ally.

State Rep. Dan Pabon, a Denver Democrat, called the Robb Street fire “the worst confluence of events that we could imagine” and said he believes legislation should be considered that would impose much more rigorous fire-safety standards on host homes.

“We need to make sure that the safety protections are in place and that these kinds of tragedies are prevented,” he said. “I think there's plenty of us who are concerned about, again, not only recognizing the extreme grief associated with this situation but making sure that it never happens again.

“If we can put some safeguards and accountability in place, that's the role of the state when it comes to protecting the most vulnerable populations.”

Contact 9NEWS reporter Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story:kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.