77-year-old woman traumatized after SWAT raided her home, no evidence found

In search of a stolen car and guns, DPD served a search warrant on 77-year-old Ruby Johnson's home and found nothing – she and her community want an apology.

Chapter 1 Denver SWAT serves a search warrant at Ruby Johnson's Montbello

Ruby Johnson, a 77-year-old grandmother, was watching TV in her Montbello home when she heard a loudspeaker call from outside – it was Denver Police asking anyone inside to come out with their hands up.

Body camera video obtained by 9NEWS shows Johnson, appearing confused and weary, approaching officers outside in a black robe and bonnet with her glasses on her forehead. She looks around, uncertain about what’s going to happen.

“I didn’t want them coming in there shooting,” Johnson said. “I came out, and then they asked me, ‘Do you have a gun on you?’ I said, ‘No, why would I have a gun on me?’”

What happened next on Jan. 4 shattered Johnson’s and her neighbors’ sense of safety, in Montbello – a mostly minority neighborhood in northeast Denver.

Montbello residents who witnessed the SWAT team at Johnson’s home question why police executed the warrant – in a case of a stolen vehicle and guns – that hinged almost entirely on the Apple tracking software Find My iPhone.

9Wants to Know conducted a months-long investigation into Denver Police SWAT knock-and-announce warrants and found that they occur more often in minority neighborhoods.

Chapter 2 A traumatizing event for Ruby Johnson

As officers searched her home, Johnson was waiting in the back of a nearby police car. She said the experience was traumatizing and led her to feel unsafe in the home she has lived in for about 40 years.

“When I start thinking about it, tears start coming down,” she said.

Johnson is a single mother who raised her kids in the area. She no longer wants her children or grandchildren to visit her because she fears the police could come back and hurt them.

Rita Whittington first befriended Johnson more than 20-years-ago in church. She said she has noticed her friend has changed since the warrant, with a new “sadness” she has not seen before.

“It’s still hurting us. It’s still affecting her,” Whittington said. “Until we see her whole again, I want to see her better than she was. I want to see her whole again, smiling again, at peace again, that feeling of violation – I want her healed of that.”

Gwendolyn Brunson, Johnson’s daughter, said she called the detective who created the warrant to seek answers.

“I said, ‘I need to find out what’s going on and who assaulted my mom,’” Brunson said. “And I said assaulted, but I did not mean physically assaulted but assaulted her mentally, emotionally because she was so upset.”

Joe Montoya, division chief of investigations with DPD, said the department did not intend to harm Johnson and regrets that the warrant caused suffering.

“We can always apologize and I’d be willing to apologize that there was a warrant issued and evidence was not found there,” Montoya said. “That’s a given, but I don’t think there was anything done to intentionally traumatize her.”

Johnson said her family wants her to trade Montbello for Houston to be closer to family because of the way DPD treated her. Montoya said he hopes that does not happen.

“I would hate to see her move from her home because of this incident,” Montoya said. “I can’t fault her for feeling that way, but we like to do everything we can to help her through that process moving forward.”

Montoya said there are various victim services programs designed to help people work through their trauma and that he hoped Johnson utilizes those in order to feel safe in her Denver home.

Whittington said she is worried she is going to lose a member of her church family to Texas. “I don’t want to prevent her, but at the same time, it’s going to impact all of us,” she said. “There is going to be a void if Ruby goes ahead and makes this decision that would be the best decision for her.”

Chapter 3 Watch the SWAT bodycam video from Jan. 4

The bodycam video shows an officer looking through boxes in the basement with other members of the SWAT team. They go into a nearby room to check on their colleagues. The footage shows one officer looking through the room and a third with his helmet off, rubbing his head in apparent frustration.

Watch a portion of body camera footage obtained in a records request and edited by 9NEWS.

“Anything, Nate?” asks one officer.

“No,” another says.

“All right, we’re going to call it good.”

Another officer on the body camera footage asks Johnson whether her grandchildren had been over recently. She says they had not.

Police didn't find the stolen vehicle, guns or cash. They did take three photos of an attic door broken while executing the warrant.

Chapter 4 iPhone pings fuel a warrant

Data shows that DPD’s SWAT unit executed 187 knock-and-announce warrants from September 2020 to September 2022 and that 64% of them occurred in minority neighborhoods.

A Denver Police division chief, Joe Montoya, said race had nothing to do with executing the warrant on Johnson's home: "When a phone pings to a home if this phone was pinging in southeast Denver, Cherry Creek, we are still going to go in and get those guns."

State Rep. Jennifer Bacon (D), who represents Montbello within District 7 in Denver, said DPD’s actions contributed to the community’s eroding trust in law enforcement.

“I am sad that we have another incident to kind of put in the folder, if you will, of a series of traumas that put us into a place that we’re questioning our safety deeply and internally,” Bacon said. “We gotta question everything. You can’t even just be at home, enjoying a day.”

The warrant conducted on Johnson’s Montbello home by the DPD SWAT unit drew additional scrutiny because it was based almost entirely on an old phone’s Find My iPhone pings.

Early morning on Jan. 3, a 2007 white Chevrolet truck with Texas license plates was stolen from a downtown Denver hotel parking garage, setting off a series of events that ended with the warrant at Johnson’s home.

The truck was stolen out of the downtown Hyatt Regency’s parking garage. The driver rammed through the gate as they fled – inside were six guns, $4,000 cash, two drones and an iPhone 11.

Jeremy McDaniel said he was in his hotel room when his truck was stolen. He said he kept the guns in locked cases in the truck because he thought they would be safe in the hotel’s parking garage.

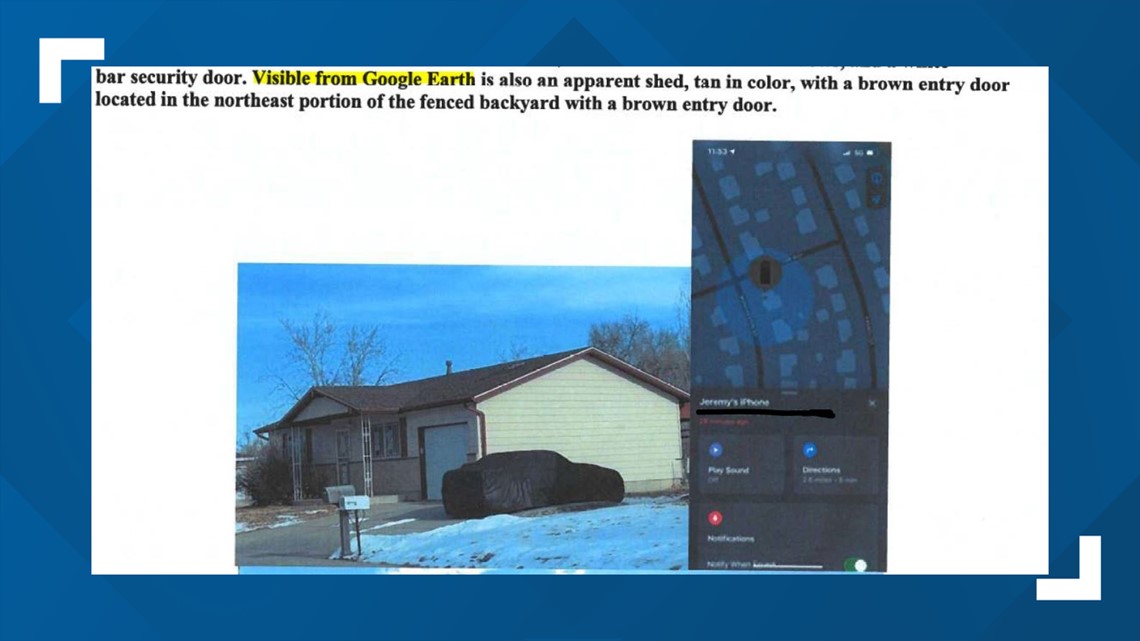

Once the hotel notified him of the truck theft hours later, he began tracking an old iPhone 11 that was left in the truck. Find My iPhone pings gave police a lead to a home in Montbello before the device died. If the phone was there, police reasoned that maybe the rest of the stolen goods would be, too. No other surveillance of the property was done, according to the warrant. DPD, eager to recover the handguns and rifle, drew up a warrant and activated the SWAT team.

McDaniel said he didn't think police treated his case with urgency, even after he told them about the stolen guns. He said he was on hold with DPD for 45 minutes and had difficulty getting them to check possible leads on the day his truck and guns were stolen.

McDaniel said he did not know what additional evidence police had for a search warrant at Johnson’s home that they did not have on the day everything was stolen.

He said he alerted police multiple times about other opportunities found through Find My iPhone to look for the stolen truck, but he felt police “blew us off,” even after he told them the guns that were inside the truck. The iPhone stopped for an hour at a McDonald’s and a 7-Eleven, but police did not go look for the truck.

“They said ‘Sorry, we just don’t have the manpower to check it out,’ even though there’s guns in it and all kinds of stuff," McDaniel said. He said the police didn’t seem to care after he notified them of the theft.

Chapter 6 Read the Denver Police warrant for Ruby Johnson's home

Chapter 7 DPD's decision to execute the warrant

“The decision was made tactically because weapons were involved, to utilize the Denver Police SWAT team to execute the warrant,” Montoya, division chief of investigations with DPD.

Bacon said more police work needed to happen before the warrant was approved. She said police could have made calls or driven by the house to see whether the stolen car was visible.

“Now there’s a whole street that saw with their eyes, an unassuming grandmother be pulled out of her home,” Bacon said. “They did not recover these things because perhaps someone didn’t feel it was worth the time to see if perhaps there was a truck outside or even to ask her if there is anyone in the home.”

Montoya said police thought Johnson was being truthful and there were not any stolen goods in her home, but they still had to go in with force to be sure. Officers have to be cautious.

“You’d like to take it at face value but you just never can,” Montoya said. “Even if it’s a senior citizen, we know that there could potentially be grandchildren, or a friend, or a neighbor or something that maybe could be in a house.”

More than a day after the truck left the hotel garage, DPD executed the warrant.

After Johnson walked out to the SWAT vehicle, they asked her where to find keys to parts of the home and lock combinations.

“We are just trying not to break things if we don’t have to,” one officer said. “So that’s why we are asking, OK?”

About a dozen Denver SWAT officers poured into the home. They sifted through boxes with the help of a K-9 unit. They used a battering ram to try to open the rear garage door. They broke down the attic door and cut the lock to the shed.

Montoya said officers researched the property and knew Johnson lived alone, which is why they used the “lowest threshold of aggression.” He said officers took the proper steps to create the warrant and approached it in a gentle way.

“I’m not going to second guess the investigation,” he said. “The proper steps were taken. The place where that would have been questioned would have been the DA’s Office and the judge’s level. And they felt comfortable signing that warrant.”

Montoya said a background check of the property showed someone with a history of low-level offenses lived in Johnson’s home at some point. That information was not included in the copy of the warrant available at the Denver County Courthouse. Johnson's family said that the relative who had those low-level offenses had not lived in Johnson's home in several decades.

Denver Deputy District Attorney Ashley Beck and Judge Beth Faragher both approved the warrant.

Kristin Wood, a spokesperson for Denver County Court, said Faragher was not open to answering questions because it would “violate the judicial code of conduct” to talk about a pending case. However, she wrote that police showed there was a chance that the items in question could be in the house.

“Judge Faragher signed the search warrant because she found probable cause existed,” Wood wrote in an email. “If a judge did not find probable cause, he/she would not sign the search warrant.”

Beck also would not comment. Instead, a spokesperson wrote in an email that the warrant passed legal muster.

“I can tell you that our office is obligated to review every search warrant the Denver Police Department writes to ensure it is legally sufficient based on the facts to which the detective swears,” Carolyn Tyler wrote in an email. “If there is probable cause to believe the stolen property was at a location, we will authorize the search warrant per CRS § 16-3-301.”

Bacon disagreed and wanted more in-person police work to be done ahead of time without reliance on just the internet. Find My iPhone and Google Earth were cited in the warrant, without any on-the-ground surveillance.

“So the questions I just have are beyond taking pictures from Google Earth, and understanding what the home looks like, what kind of reconnaissance did they do, to even ask or if anyone had seen a vehicle?” she said. “Or to see if the vehicle was even there before they forcibly entered a home so much so that it was damaged.”

Neither Wood nor Tyler would answer follow-up questions about why the deputy district attorney and judge thought the probable cause was established at this location without on-the-ground police work from DPD.

Doug Schepman, a DPD spokesperson, wrote in an email that the truck was recovered two days after the warrant was executed about six miles away in Aurora. He said the stolen guns were not in the truck and no arrests have been made.

Chapter 8 Analysis of Denver SWAT warrants

A 9NEWS analysis of DPD warrant data found more SWAT knock-and-announce warrants, like what happened at Johnson’s house, occurred in minority neighborhoods over the past two years.

“Knock and announce” is a term used to describe a police search done by a heavily armed SWAT team that announces their presence to residents of a location where a warrant is being executed. It differs from an immediate entry warrant that is similar to the type of SWAT action shown in movies and TV shows where officers kick in the door without warning.

The data shows that DPD’s SWAT unit has executed 187 knock-and-announce warrants from September 2020 to September 2022. 9NEWS found that 64% of them occurred in minority neighborhoods.

“Race had nothing to do with where that phone pinged,” Montoya said. “We don’t – when a phone pings to a home if this phone was pinging in southeast Denver, Cherry Creek, we are still going to go in and get those guns.”

Graphic created by Zack Newman.

Sharon Battle, Johnson’s neighbor, said she does not think a SWAT warrant with this much force would have happened in other parts of Denver.

“Would it happen in Northfield?” Battle asked. “Would it happen in Highlands Ranch? Would it happen in Cherry Creek? Doubtful. And I think even if it did, someone would have asked reasonable questions. I just don’t think it would have happened anywhere else.”

On the body camera footage, an officer asks his colleague if they ran a background check on Johnson’s son while executing the warrant.

“Did they - is her son, have they run him? Is [he] a criminal? Better way to put it?”

Battle was one of the first people to raise questions with police about why this warrant happened. She said she thinks police are doing the best they can but that they could do better. She said the main improvements could come by better connections with the community, by giving people in the neighborhood more of the benefit of the doubt and to not hinge warrants on Find My iPhone pings.

“So I think they could learn that everyone is not a criminal in the neighborhood,” she said. “I think that they could learn that it could be better for everyone to operate with some compassion and empathy, rather than to rush it.”

The data showed neighborhoods with the highest prevalence of knock-and-announce warrants include:

- Westwood had 16 warrants served, a neighborhood that Census data estimates as 80% Hispanic.

- Montbello had 12 warrants served, where 65% of residents identify as Hispanic and 19% as Black, per Census data.

SWAT knock-and-announce warrants have occurred in white neighborhoods. Nine occurred in Hampden, making it the third most. According to Census data, Hampden is 63% white.

The data shows knock-and-announce SWAT warrants have occurred in:

- 89% of Denver's 27 majority-minority neighborhoods.

- 57% of Denver’s 51 majority-white neighborhoods.

Hover your mouse over each neighborhood to see more details about SWAT activity there.

Graphic created by Zack Newman.

Bacon said that crime is an issue in the Westwood and Montbello neighborhoods. She said how police show up to respond to crime there matters.

“If we’re going to see police, can we see them doing other things than showing up with a tank to help us collectively bring down these [crime] numbers?” she asked. “But right now, the things that we’re facing, as met by the people who are supposed to support us, just equal a big ball of trauma.”

Bacon said the execution of these warrants is the type of police interaction that causes community members to lose faith in law enforcement.

“These are the types of things that cause them to not report crime,” Bacon said. “These are the types of things that people see that causes them to not call police for help because I don’t know how they will be met, how they will be seen as a suspect. These are the things that happen that cause people to believe that Denver Police doesn’t value their neighborhood, their things or their own sense of safety and how they fit in the whole narrative around crime.”

Battle said she wants police to remember that the job is to “serve” and “protect us as well.”

Montoya said police will aim to execute warrants as safely as possible.

“Our goals are out there to protect the community,” he said. “And part of protecting the community is investigating crimes. And the evidence will lead us to certain areas and when it does, we are going to take all these steps and precautions, to go into a home, a car, contact someone on the street, utilizing under the constitution, utilizing the safest methods in which to contact people.”

But he said they know that they need to create opportunities for conversation after a SWAT warrant to create a space designed for “healing.”

“We do understand how we need to try to do things better,” Montoya said. “What we are learning is that in situations like this, what we need to start doing and what I believe we are going to start doing is follow up with these communities after an event like that occurs.”

Back at the church, Johnson and Whittington embraced and acknowledged that recovery may require continued help and could take a while. Whittington called the recovery “a process” and asked if Johnson planned on talking with a therapist. She said that healing may require more than spiritual support.

“Because this is traumatic,” Whittington said.

“Yes, it was,” Johnson said. “It was.”

Reach investigative reporter Zack Newman through his phone at 303-548-9044. You can also call or text securely on Signal through that same number. Email: zack.newman@9news.com. Call or text is preferred over email.

Contact reporter Angeline McCall by email or phone:

angeline.mccall@9news.com

303-871-1491

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Latest from 9NEWS