DENVER - Jail may not be the best environment for getting mental health or substance abuse treatment. But it beats the streets. It also beats jail programs in Denver just a year ago.

Each morning at the Downtown Detention Center starts with a daily dose of medications. A nurse from Denver Health, tray of pills in-hand, walks with a Denver sheriff deputy to each cell in a mental health pod.

“You have meds,” the deputy says through each cell. A slot in the door opens and the nurse gives the inmate his prescribed medication.

“We have possibly, anytime 2,100 to 2,300 inmates in both facilities. Sixteen percent are on anti-psychotic medication, which tells you just how severely ill they are,” said Sasha Rai, the jail’s director of behavioral health.

Rai doesn’t often use the word inmate.

“I always call them my patients,” he said

He may work in a jail, but he said he treats it as a clinic, providing men and women a service they desperately need.

“Sometimes they won't even get the care outside. It takes a couple of months to see a psychiatrist in the community,” he said.

Once a staff of three medical professionals showing up a few times a week is now a full-time team of nearly 20 Denver Health employees. The City and County of Denver entered an operating agreement with the hospital in 1997.

The 2018 city budget includes $4 million for medical services for arrestees, pre-trial detainees and inmates at the hospital, as well as $13 million for health care services at the Denver County Jail and Downtown Detention Center.

The money allows Rai and Bradley McMillan, longtime supervising psychologist at the jail, to provide a better level of care for people in jail.

“We are definitely now providing a lot more counseling services, a lot more group therapy services and certainly having a lot more connections with community agencies,” McMillan said.

The doctors said more resources are coming. That includes up to six nurses who will staff the jails overnight so there’s always a behavioral health professional available to inmates.

Doctors and nurses work alongside sheriff deputies who have also had updated training known as Crisis Intervention Training (CIT). CIT is specialized training in how to respond to calls concerning persons with mental illness in crisis.

“It’s easier to sit there and talk with someone through their door and kind of decide what’s going on, more so than going in there and using force,” said Deputy Sheriff Gregory Liggins. “We treat these guys as if everyone is different and we interact with them as an individual instead of just a number.’

For example, deputies found a way to get one mentally ill inmate, who had spread his feces all over his cell, calm enough to take his medication. Liggins said he sees a general difference in how inmates respond to their commands, and inmates have said they see a difference in themselves thanks to the jail’s approach.

“I feel like now there’s people out there that give a crap and actually want to help me instead of just being handed my property … whatever I had on me when I got arrested,” said Zachary Johnson, who has been using heroin since he was 15. “When you are looking at 50 and you realize that two-thirds of your life has been wasted, it’s kind of a wakeup call.”

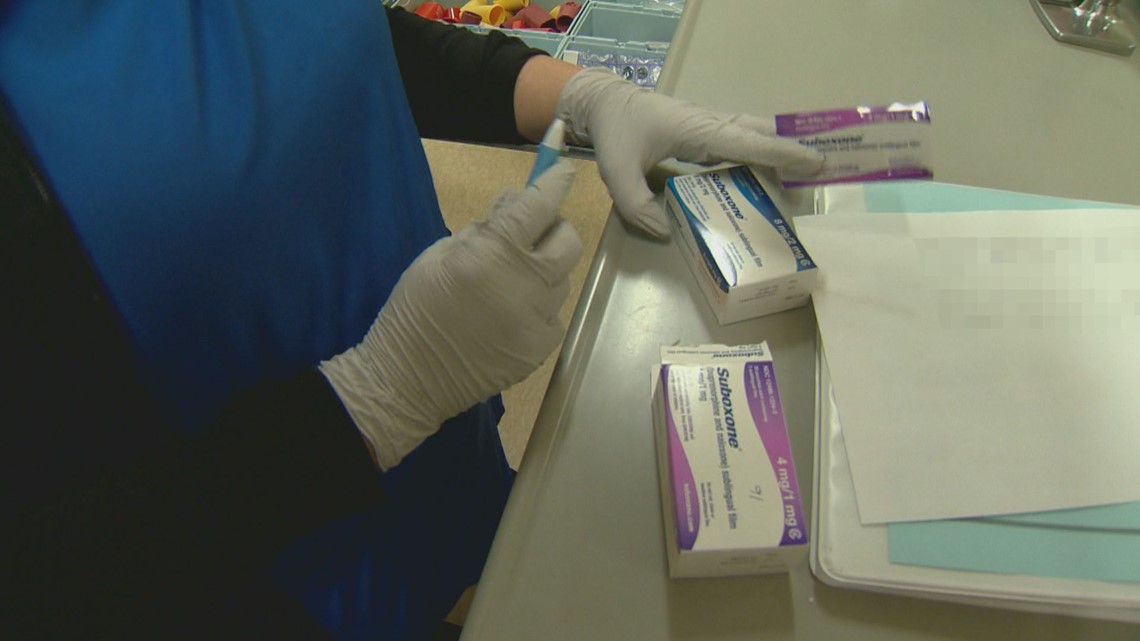

Johnson said he is feeling the effects of the many counseling services available, including Denver Jail’s new Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT) program. The MAT program allows Denver Health nurses to give opioid addicts like Johnson drugs, such as Suboxone, to help fight addiction.

Suboxone is a prescription used to treat adults dependent on opioids.

“I get 8mg every day, which eases the physical cravings for drugs and also will block the effects of drugs when I get out,” Johnson said. “So, I can use but I won’t get high. I know that intellectually. So, I probably won’t waste my time trying to get high.”

Johnson said he’s been hospitalized three times in the last year for overdoses. He said he’s spent countless days in jail since he turned 18. He also said he hopes this time will be different thanks to MAT and some transitional services.

Johnson added that he’s worked with community resources from jail to get housing, which he believes will prevent him from going back to the streets where it’s easy to find and use heroin.

“I think getting right treatment here and then connecting them to treatment outside, effectively, would prevent them from coming back,” said Rai, who would like to see the jail expand its transitional services.

Preliminary numbers show about 35 percent of the inmates getting MAT continue doing so after release. Rai said that's actually pretty good and beats Denver Health’s numbers.

“So people really want care, they just don't know how to get it,” he said.

About a quarter of the people who show up to the hospital for an overdose continue treatment at a methadone clinic after release.

Rai and McMillan added that the current resources are nowhere near enough to solve society's biggest problems. But they said they're now providing more hope to those who want help, and that just might create some much-needed jail vacancies.

“Don't give up. Because a lot of people have given up on me,” Johnson said. “I gave up on me. Don't give up because everyday someone wakes up, that's another day they could change. People can change.”