COLORADO, USA — No mother imagines spending days looking for her son on Colfax Avenue in Denver, but it's become Sandra Sharp's reality since her 28-year-old son Drew had his first psychotic break about 10 years ago.

“Most recently when he was willing to go into a program, there were no beds," said Sharp. "And so there wasn’t an option, and since that time, he’s been homeless and his situation has worsened."

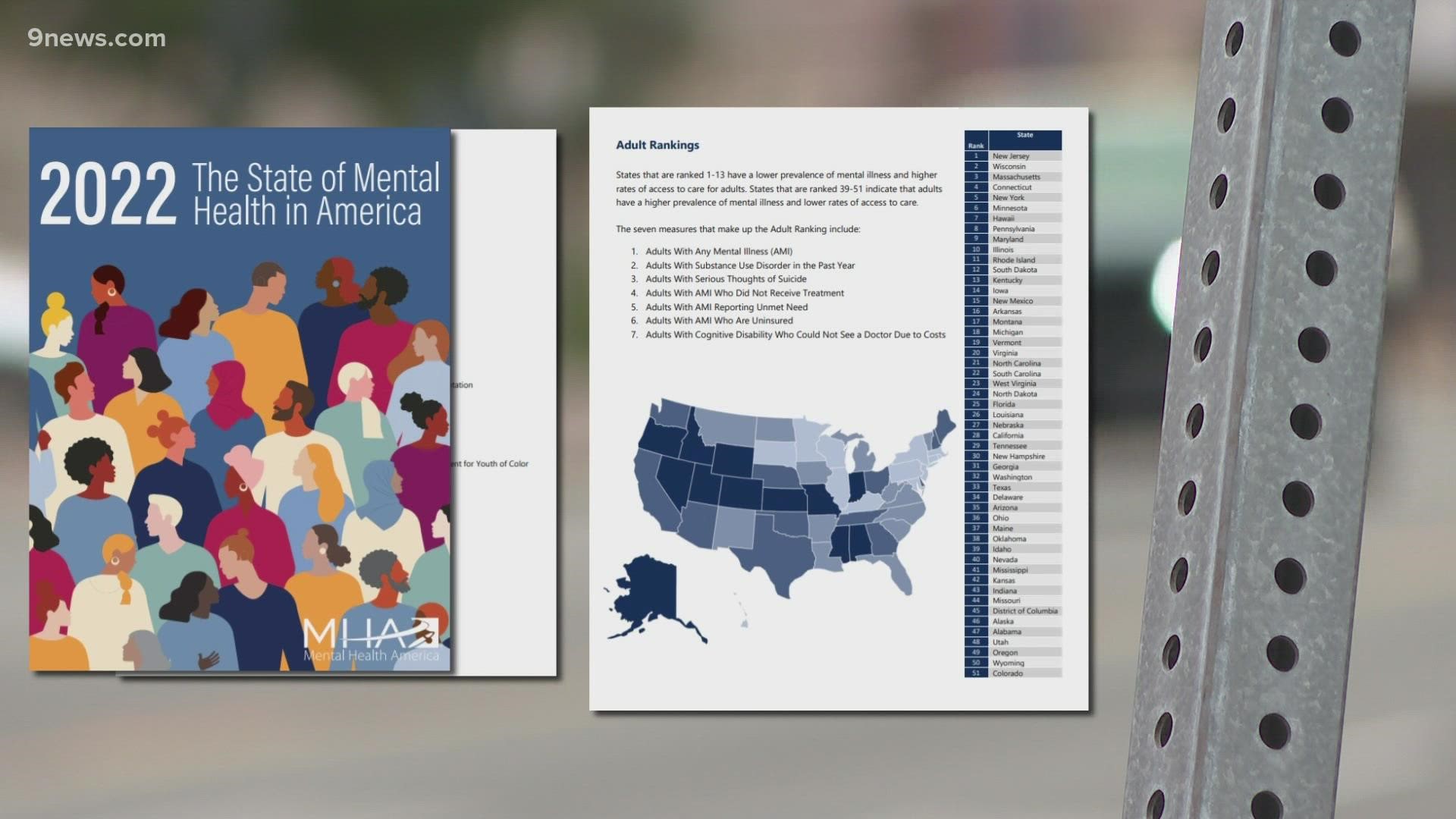

On Wednesday, the yearly Mental Health in America Report came out that ranks states access to and quality of care.

The data is from 2017 and 2018, so it does not include the pandemic, but the report ranks Colorado last for care and access for adults.

Sharp is not surprised.

“I am not a trained psychologist; I am not a trained psychiatrist," she said. "He needs that care. And without that care, it’s just like someone with cancer who is not allowed to see an oncologist and instead is seeing a pediatrician – or instead is seeing a medical assistant.”

The CEO and President of Mental Health Colorado looks at the national rankings every year, and while Vincent Atchity said this data "does not reflect the experience that we've had these past 19 months," he knows mental health care and access to it is still in crisis.

"Family after family discover to their great dismay that wow it’s close to impossible to get timely quality care for someone you love," said Atchity.

He said while Colorado has consistently ranked in the lower third of this national report, changes have been made on the legislative level that have not been implemented yet.

The national report does show Colorado improving when it comes to a greater access to care for youth, but Atchity said "that is pre-pandemic data and I would say a blip that is not representative of where we are right now."

He pointed to Children's Hospital Colorado declaring a 'State of Emergency' for youth mental health in May of this year.

Last week, several American pediatrics associations declared a national state of emergency for children's mental health.

“One of the things that we’re most concerned about are the rate of suicide in the state of Colorado," he said. "We’re one of the top ranked states for both adults and youth. We’re also one of the top ranked states when it comes to opioid use and opioid related overdose deaths."

One of the biggest problems Mental Health Colorado sees is the shortage of psychiatrists and high level specialists in behavioral health.

According to a recent Department of Health and Human Services report, just 34.69% of Colorado's mental health care needs are being met.

Atchity said he can't see a pathway out of that right now.

Colorado did receive $450 million from the America Rescue Act that they will allocate to behavioral health, and while Atchity is the chair of the taskforce that will make recommendations on how it's spent, money can't solve every issue.

"The challenge is money can build space and retrofit space but money doesn’t make healthcare providers appear out of thin air," he said. "So I’m not entirely sure what we’re going to do about this workforce issue right now."

Atchity said the state needs to think beyond normal solutions and reserve access for formal care to people with serious conditions.

Without enough professionals, he said people can take steps in their own lives to check in on each other.

"Making peers more readily available through clinical settings is a pathway forward, but beyond that, peers in a more generic sense – that is who we are to each other," he said. "And the way we are able to recognize each other’s needs and be more effective in supporting each other’s well being, that’s what we’re really going to have to fall back on."

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Latest from 9NEWS