GRANADA, Colo. — About as far away as you can get from anywhere in eastern Colorado sit the remnants of a largely forgotten chapter in American history: an internment camp where thousands of U.S. citizens were detained during World War II.

Their offense? Japanese heritage.

None of the approximately 7,300 Japanese Americans detained at Camp Amache, nearly 200 miles southeast of Denver, were accused on any crime.

Instead, driven by fears of traitors amid its own citizens, the federal government detained about 120,000 Japanese-American men, women and children for the war's duration. Many of the detainees were farmers from California who remained in Colorado after the war's end. Camp Amache was one of 10 detention sites.

Saturday, a handful of former Camp Amache detainees visited the site in an annual pilgrimage that grows smaller as each year passes.

"What they did to us was absolutely unconstitutional," said Robert Fuchigami, who was 12 when he and his family were forced to abandon their California farm. "The country made a terrible, terrible mistake."

Like thousands of others detained at the Granada Relocation Center, Fuchigami went to school, helped grow vegetables and watched as adult Japanese-American men volunteered for the military.

The camp, named after the Native American wife of an early settler of the area, was deliberately placed far from anywhere else. A rail line allowed camp managers to shuttle detainees in via train, many of them stumbling off the cars in the dark as they arrived. The camp was ringed by a barbed wire fence punctuated by guard towers and covered a square mile of dusty, scrubby land a few miles from the historic Santa Fe Trail.

Today, the barracks, dormitories and central buildings are gone, their crumbling concrete foundations marking the outline of what at the time was Colorado's 10th-largest city. For decades, local schoolteachers and children have been sharing the story of Camp Amache, and recently won it recognition as a National Historic Site.

A new guard tower looms over the detention center — "call it a concentration camp," says Fuchigami, now 84 and a Navy veteran and retired university professor — and interpretive plaques explain the site's history.

"When you talk about Colorado, everyone just thinks about skiing," said Ian DeBono, the retired superintendent of the local school district who volunteers with the Amache Preservation Society. "This is part of our history."

DeBono said that when he arrived in the area in the 1970s, some locals still used ethnic slurs to refer to the camp. Those attitudes have changed with education and the help of high school students who run the small interpretive museum, he said. The U.S. government formally apologized to those held in the relocation centers and paid reparations. And a 1982 congressional commission concluded there had never been any "military necessity" for the detention camps.

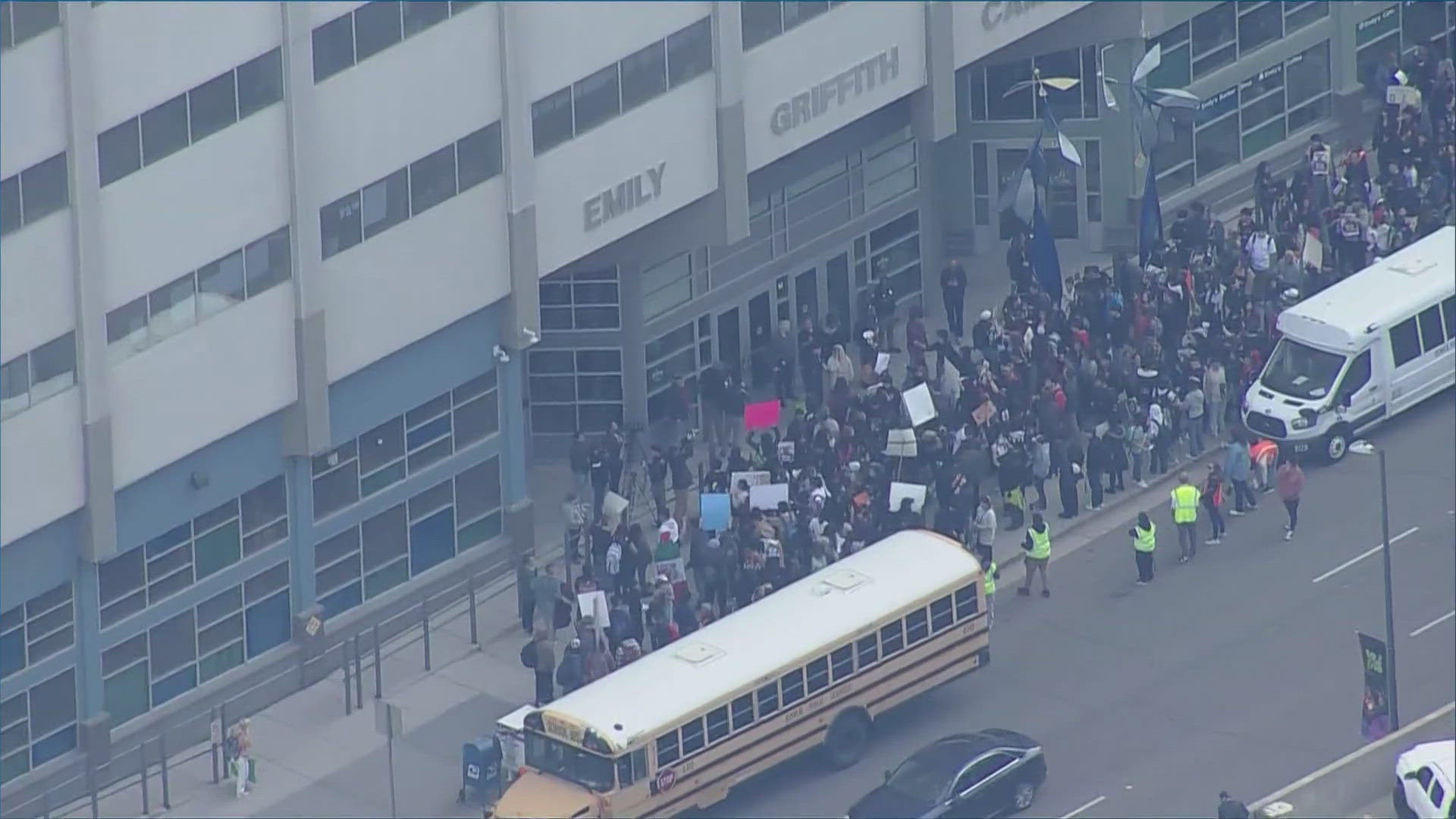

On Saturday morning, the American flag above a memorial stone fluttered in the stiff breeze as about 250 people made a pilgrimage to the site in honor of Asian-Pacific American Heritage Month. Placing flowers at the base of the gray stone, they bowed silently and paid homage to the people who lived and died at the camp.

The number of actual camp survivors dwindles each year, with only about 15 still alive in the Denver area. Another slightly larger group lives in California.

Fuchigami said this was likely his last visit. He said he's glad to see the newly erected guard tower standing over the site, because it helps visitors understand that the people living at the camp had no choice. When the camp was closed, residents were turned out with almost nothing, with nothing to return to.

"It was the growing pains of a young nation," Fuchigami said as he looked over the camp site one last time. "We make mistakes. The nation made mistakes. The loss of freedom is the worst thing that can happen."