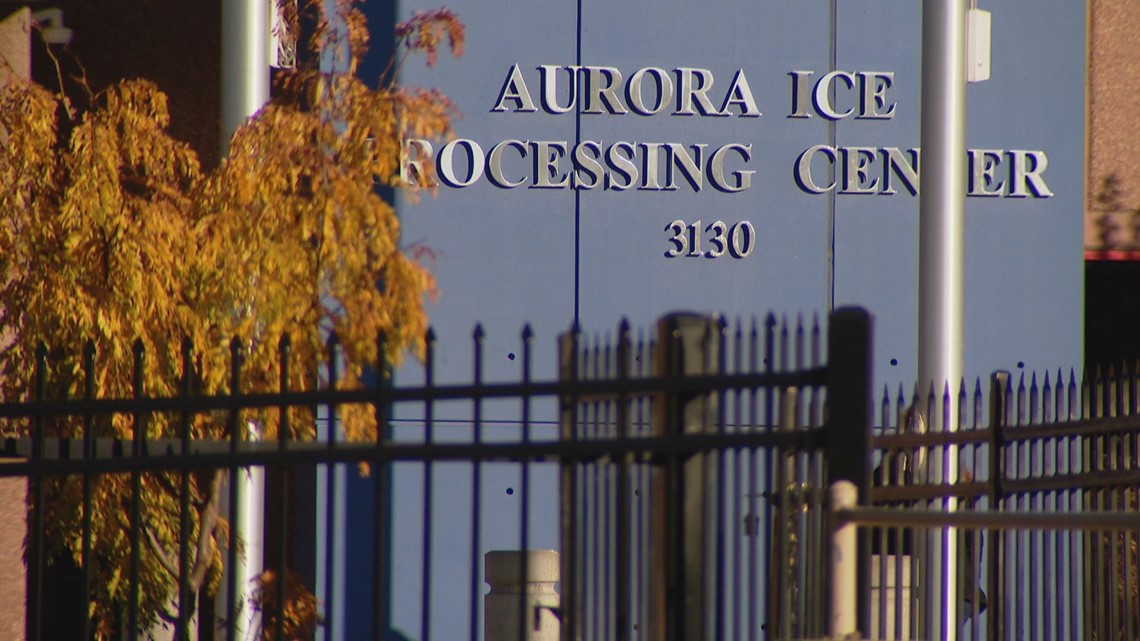

DENVER — When someone is released from the ICE detention facility in Aurora, they could find themselves getting help from Andrea Loya and her team.

"A lot of them have gone through really traumatic things in their own countries, which has led them to look for a better life here," she said.

She's executive director of Aurora-based Casa De Paz, who has worked to provide a safe space for immigrants released from the facility while they work to plan out their next steps. This past Tuesday, Loya said the organization helped 29 people.

"Every time that you see bigger numbers, it just means that those people don't have to sleep in a ICE detention facility that night," she said.

Depending on where an immigration arrest in Colorado is made, there is a chance that person could be held in another jail before being taken to the facility in Aurora.

That's because of what's called an intergovernmental service agreement (IGSA), which ICE defines as, "A cooperative agreement between ICE and any state, territory or political subdivision for the construction, renovation or acquisition of equipment, supplies or materials required to establish acceptable conditions of confinement and detention services."

It's the type of agreement that allows jails in Colorado to help ICE with detainment.

According to the agency, there are just two IGSA's in the state right now - in Teller and Moffat counties.

The Denver office also covers Wyoming, where there is one ISGA.

But state Democratic lawmakers want to do away with such agreements through HB 23-1100 that is now under consideration by the Senate.

According to the bill, if passed and signed into law, state and local governments would be restricted from entering into an agreement for the detention of individuals, and receiving any payment related to the detention of individuals in an immigration detention facility that is owned, managed or operated by a private entity, among other things.

The law would begin in January 2024.

The bill argues in part that, "...the agreements are an inappropriate exercise of state's police powers."

Now retired, John Fabbricatore served as director of Denver's Field Office for ICE. He testified against the bill, arguing that the agreements in place help with bed space at the Aurora facility, helps with resources, and improves safety for ICE agents.

Fabbricatore used the example of Teller County, when agents have to transport those arrested to the Aurora facility.

"When you have such a huge state like Colorado that you're dealing with and all the aspects of the environment, the mountains, the weather, all these other things, we really needed those other jails as kind of halfway points to get the cases to Aurora," he said Thursday in an interview. "So what this law does, in essence, is it's limiting the bandwidth that we have."

While he acknowledged that the amount of agreements in the state is small, he argued that the demand can fluctuate, which is why he felt it's important to keep the ability to make such agreements in place.

"At certain times we've used - because of different populations or how arrests were going - we could make these agreements with law enforcement. And again, that's part of the overall tactical look at things that law enforcement has. Like we should be able to have this ability to say, 'OK we need to do this.' You know, 'We can cut back here.'" he explained.

Just last month, a District Court sided with Teller County ruling their agreement with ICE was legal.

In 2019, now former Denver Police Chief Paul Pazan was vocal about the department not wanting to assist ICE agents with detainment.

As for Loya, she believes the funds that are used in the agreements could be used differently.

"So there's ways that we can spend that money better and actually provide folks with a - like a better way to do these things," she said.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Latest from 9NEWS