A 'horrific privilege': The untold story behind the officers at the Aurora theater shooting

<p>While everyone else was running out of the Century 16 movie theater in Aurora on July 20, 2012, these officers were running in. For the first time in five years, hear their story. </p>

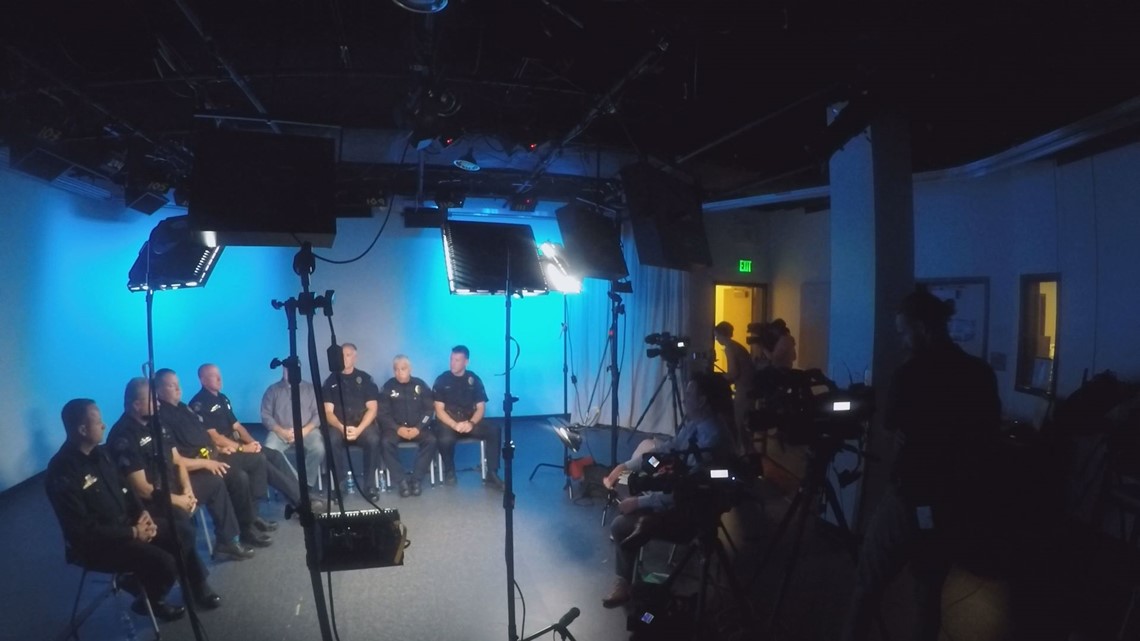

In their first televised interviews since the Aurora theater shooting, eight of the responding police officers tell 9Wants to Know their recovery is ongoing. Some are doing better than others. Some continue to struggle with their experience. This story attempts to discuss their actions in a way that allows the reader/viewer an opportunity to better understand the mindset of the officers five years after their response.

Sometimes it’s nothing more than a noise. A cell phone rings. A fire alarm blares. In an instant, they’re back inside Theater 9. Bodies are everywhere. Someone covered in blood is begging for help. There’s gas in the air.

Aurora Police Sgt. Gerry Jonsgaard calls it “a dark place.”

“You’re just sitting there sometimes, and it closes in,” the Aurora Police Department veteran said. “I talk to some people who say they have the same thing.”

Five years after he and his colleagues responded to one of the worst mass shootings in this nation’s history, Sgt. Jonsgaard says he still thinks about the events of that night nearly every day.

“I don’t think anyone who responded to that theater walked away the same person,” he said. “It’s impossible.”

It’s a common refrain within a community of police officers that is still dealing with the aftermath of the response to what happened in Century 16’s Theater 9.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS: Letters from the theater shooting survivors 5 years later

THE EVACUATION OF THE WOUNDED

Officer John Gonzales no longer believes the attack was over by the time he arrived.

“I could still hear the gunfire when I got up to the door,” he said.

He’s convinced of it now, even though a report commissioned years ago by the city of Aurora concluded otherwise.

Regardless, his training told him he needed to get in and find the shooter.

“That’s what we do,” he said. “That’s what you signed up for. That’s what you’re trained to do. That’s why you go in.”

After receiving a gas mask from a fellow officer, Gonzales – a trained SWAT team member – burst into Theater 9.

That’s when the enormity of the situation hit him.

He didn’t immediately spot any shooter, but he did see wounded people everywhere.

“You knew there were going to be people who were not ever going to leave that building,” he said.

Outside, Officer Jason Oviatt was headed toward the rear exit door to Theater 9.

Instantly, his eyes were drawn toward a man with a gas mask and body armor.

“When I first saw him, I thought he was a cop,” Oviatt said.

The more he looked, the more he realized the man wasn’t wearing the type of gear Oviatt was used to seeing.

Seven minutes after the first 911 call, Officers Oviatt and Jason Sweeney arrested the shooter without incident.

Back inside the theater, Officer Jon Marek heard Oviatt’s radio call. He wasn’t convinced the attack was over, however.

“My thought was, ok, we’re looking for a second person,” Marek said.

There were too many wounded, and there was a shotgun on the floor.

Marek had already seen a rifle near the rear exit door when he went in.

Two long guns told him there may be two shooters.

FULL INTERVIEW: Aurora Police Officer John Marek on entering the theater

Sgt. Jonsgaard found the environment around him horrific.

“The volume of that night was just beyond your senses,” he said.

He had seen plenty of trauma during his career, but nothing quite like what he saw all around him inside Theater 9.

And then there were the fire alarms, distinctive and pulsing. They just kept blaring.

Yet, that wasn’t even the worst sound, according to Jonsgaard.

Once word began to filter out of the area and onto social media of the shooting, the cell phones started to ring within the theater. Many of the phones belonged to people either seriously wounded or dead.

The sound was brutal on the officers.

Jonsgaard said it took him years to feel comfortable around the sound of a random cell phone ringing.

“[They] used to make me so mad,” he said. “They’d be ringing and I’d want to throw them out the window.”

PHOTOS: The officers behind Aurora Theater shooting response

Before James Waselkow became an Aurora cop, he served one tour in Afghanistan with the U.S. Army.

It hardly prepared him for what he saw the moment he walked into Theater 9.

“You just don’t expect to see those things in the United States,” he said. “It was just carnage. It was just people shot.”

“There was a lot of blood,” he added.

Lieutenant Stephen Redfearn (then a sergeant) quickly grew frustrated with the sheer number of wounded patients and the lack of ambulances nearby.

Officers like Waselkow were carrying out the wounded, one by one, to a few spots just outside of the theater, but many of the responding ambulances remained much too far away to be of any good.

“[I thought] we’ve got to do something,” Redfearn said. “These people are dying here, and we’re not getting the help we need.”

A city-commissioned after-action report would later conclude that a variety of factors – including crew safety and lack of accessible pathways – contributed to the ambulance issue.

Standing outside with the wounded, Redfearn remembered a much smaller active shooter case from 2010 in which officers placed a victim inside a police car in order to take him out of the immediate area.

“That crossed my mind,” Redfearn said. “Hey, it worked once, it can hopefully work again.”

Bryan Butler, now retired, called the lack of ambulances frustrating.

“We’re not paramedics. We’re not doctors. We can’t help them,” he said.

But they could drive their cars to the people who could ultimately help the wounded.

Redfearn began marking on a latex glove where he was sending each of the many victims. One side represented Medical Center of Aurora. The other represented University of Colorado Hospital.

Sgt. Mike Hawkins (then an officer) took two of the wounded in his car to University Hospital.

“A firefighter stopped me and said, ‘Do you have a car?’” Hawkins said.

One of the wounded was clearly dying.

“The firefighter said very quietly to me, ‘You need to go like hell. You need to get there fast,’” Hawkins added.

Twenty three of the victims who went to University of Colorado Hospital arrived in police cars.

“The doctors told us afterwards everybody with survivable injuries survived,” Redfearn said.

A HORRIFIC PRIVILEGE

%

Hawkins – the officer who raced two victims to the hospital – also had one of the most heart-wrenching tasks that night.

Veronica Moser-Sullivan, 6, was with her mother that night.

After the shooting, Hawkins came across the little girl.

“I could not find her pulse, and Sergeant Jonsgaard told me to stop it and just get her out of here,” Hawkins said. “I ran out with her, and when I got to the parking lot, I realized she had expired.”

Jonsgaard said it was the right call.

“No child was going to be left at that scene,” he said. “It was horrific enough without having to have one of my officers step over the body of a little girl at the near door. That was just not going to happen.”

Hawkins, a father of six, agreed with Jonsgaard’s decision, although he said he’s still haunted by what he had to do that night.

“There was a period of time when it became sort of a PTSD experience for me to carry my daughter upstairs to bed,” Hawkins said.

Eventually, Hawkins said he got the opportunity to tell Veronica’s parents what had happened.

“It was important to me that they knew that she was taken out by a daddy, and that I have a daughter that age, and that I am very cognizant of what was lost,” he said.

In the end, Hawkins called it “a horrible privilege.”

“This will always be a part of you,” he said. “For better or for worse. I’m trying to look at the better aspect of it.”

'WE’RE DOING OK'

Every one of the eight officers interviewed by 9Wants to Know said he agreed to talk because he wanted to speak on behalf of the many people who simply aren’t ready to speak in such a public way.

“I think we’re doing ok,” Waselkow said.

Some are clearly doing better than others.

Redfearn, for example, said he finally feels like he’s in a good place.

Oviatt said he feels the same.

“The department is healing, just like the rest of the community,” he said.

None of the officers felt like they had a lot of time to try to process what they had experienced that night, however.

“We were back to work within 12 hours,” Butler said.

“We went back that night,” Jonsgaard said.

Gonzales, for one, told us he purposefully tries to avoid the theater these days.

“I just have no desire to be back over there,” he said. “Not that I’m trying to block anything, I just don’t see the point. I don’t want to go back down there.”

Some would like to know more about some of the people they helped save that night. Gonzales helped rescue a man who was believed to be dead. The man was on the theater floor underneath the body of another victim.

“One of the other officers said, ‘I don’t think he made it.’ I said, ok, we’re moving on, and then I came back. There was just something about him. It didn’t feel right to me,” Gonzales said.

“We almost left him behind,” he added.

Jonsgaard said a man he has yet to meet actually yelled out to officers when they were loading up victims into the police cars.

The man pointed at Caleb Medley, one of the most seriously wounded, and asked them to take him first.