DENVER — When Branch Wroth, 41, died underneath a pile of officers in Rohnert Park, California back in 2017, the police department turned to a well-known San Diego doctor to help convince a jury the officers’ actions had nothing to do with Wroth’s death.

Dr. Gary Vilke told the jury Wroth died of “sudden cardiac arrest.”

During closing arguments, the attorney for the Wroth family could hardly contain his disgust over that conclusion.

“Dr. Vilke’s testified in dozens, over a hundred cases, consistently opining case after case that the police did nothing wrong," Izaak Schwaiger told the jury. "t wasn’t them. It was something else,”

“He’s a hired gun,” he added.

PART THREE: Loophole in Colorado law allows certain officer-involved deaths to avoid public scrutiny

Vilke is used to the accusations. When 9Wants to Know spoke to him from his southern California home, he shrugged off the “hired gun” comment.

“I’m paid for my services, so I do get paid," Vilke said. "I am hired, not necessarily a hired gun in my mind. I get hired for my expertise.”

That expertise has kept Vilke close to police departments for decades.

When officers and departments are sued after someone dies while being held in a prone position – facedown and frequently handcuffed – Vilke has proven more than willing to share his research with juries and judges.

The prone restraint, Vilke will tell them, almost always had nothing to do with their deaths.

“The answer is, ‘No,’ that position itself is physiologically neutral,” Vilke said.

He bases that conclusion on the research he started in the mid-1990s. People can handle multiple people holding them prone for long periods of time. That’s how he’s testified and continues to testify in use-of-force cases.

There’s just one problem.

Juries and judges sometimes don’t always buy his science. And this year, after paying Dr. Vilke tens of thousands for his services as an expert witness, the Rohnert Park Police Department ultimately shelled out $2 million for the death of Branch Wroth.

“People may believe it, they may not believe it,” Vilke told 9Wants to Know. “That’s why we have jury trials.”

He says his science is sound, however. Sure, he acknowledges, it might not look great from an “optics” standpoint.

“It looks a lot better, it’s a lot less confusing if the person has a cardiac arrest with nobody on top of them as opposed to if there are several people holding them down,” he said.

Court filings pushed by law enforcement agencies seem to agree. It’s not the cops who are killing people below them, it’s the bodies of the people below them that are failing in ways that have nothing to do with the cops.

When Tony Timpa died after being held handcuffed and prone in Dallas in 2016, lawyers representing the Dallas Police Department filed a motion suggesting the science is settled.

“According to scientific consensus, there was no reason that the officers should have concluded that their prone restraint of Timpa was in any way dangerous,” reads the motion.

But that’s not the case, countered Schwaiger.

“If there’s scientific consensus,” he said, “it is the opposite.”

Dr. Stephen Bird, a professor of Emergency Medicine at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, said the theory that law enforcement officers cannot kill someone held prone can lead officers to improperly believe their actions are inconsequential in the deaths of the people below them.

“In my experience, yes, that is the case sometimes,” Bird said.

People don’t die, he said, in a way many might think. It’s not because they can’t breathe in enough oxygen. Rather, he said, it’s because their bodies cannot purge enough carbon dioxide.

It’s a process any doctor knows well: acidosis.

“This is really a serious, scary, severe medical time where, if we don’t do the right thing, these patients can die,” Bird said.

Think of it like that cramp you get in your side when you run sometimes.

“That’s lactic acid,” Bird said.

When the human body needs more oxygen – while exercising or, as it relates to this story, struggling with officers – your body makes lactic acid.

“As acid levels go up, the pH level goes down," Bird said. "It can be a little confusing."

The more energy the body needs, the more acid is produced and the lower the pH level goes.

“Normally, your body purges that acid as you breathe deeper and faster, thereby exhaling off carbon dioxide,” he said.

But when something limits one’s ability to breathe in and – in particular – out? Acid levels continue to rise and the pH continues to drop.

The human body tends to like a pH of 7.4.

When the pH dips below 7.0, it can turn fatal.

“Even a small degree of ventilatory impairment – decreased ability to ventilate – in a setting of severe metabolic acidosis has severe consequences,” he said.

His advice to officers? It’s simple.

“Once the suspect is handcuffed, get off of them,” he said. “In my opinion, that would save lives.”

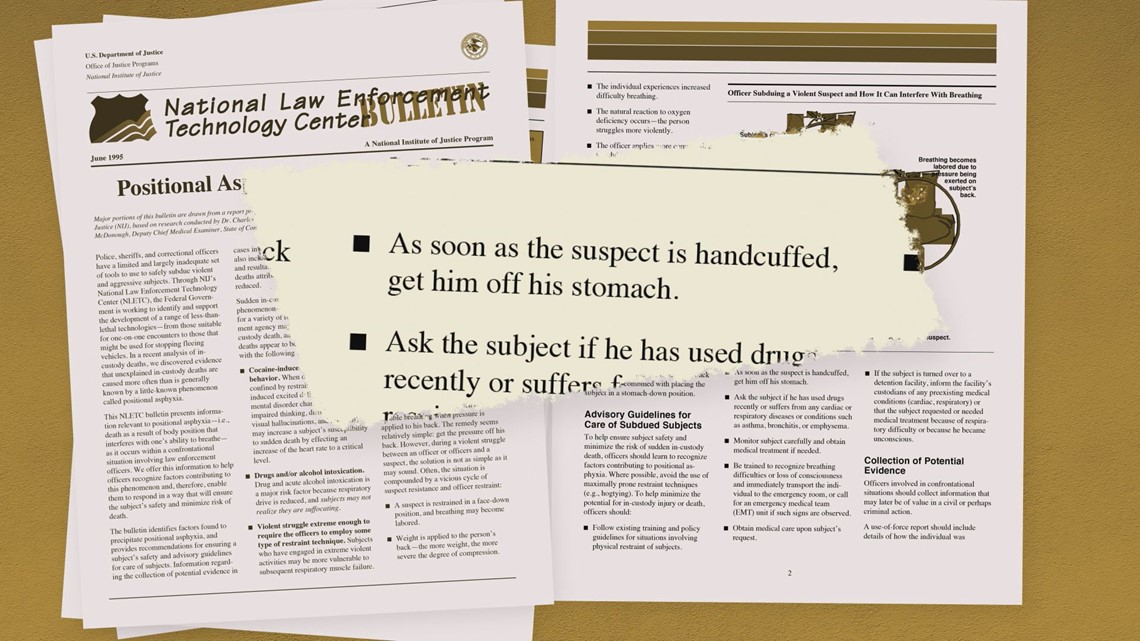

It’s what the U.S. Department of Justice told officers to do in 1995 when it issued a bulletin stating, “As soon as the suspect is handcuffed, get him off his stomach.”

Interestingly, Vilke doesn’t disagree.

“If the suspect is being compliant, yes, absolutely, no weight is necessary,” he said.

He also said acidosis should be considered in these deaths.

“I think there are certainly some cases where metabolic acidosis probably is contributing,” he said.

But his research hasn’t focused on it as a possible explanation.

“We have not really looked at acidosis from the perspective of my particular research,” he acknowledged.

It’s not easy for cases like Wroth’s to make it to a jury. Many are thrown out before the two sides even broach the subject of a settlement.

But when cases do make it past some legal hurdles in the federal court system – qualified immunity being primary among them – it’s not unusual at all to see seven-figure settlements or verdicts in these types of cases.

INTERACTIVE GRAPHIC: Click on the photos below for more information on the dozens of people 9Wants to Know died in police custody after being held in a prone position, and the settlements their families received.

Of the 107 deaths 9Wants to Know found that followed prone restraint, at least 40 resulted in either a settlement or a verdict. Our analysis found a total payout in those 40 cases of $73,113,000.

That amounts to an average of $1.83 million per case.

Schweiger said it’s the kind of money that should send a message to law enforcement officers across the country.

“I think you have to change this culture in police departments where they believe they can do no wrong,” he said.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Prone