What happened to Bobby Bizup? Questions remain decades after boy disappeared from Catholic summer camp

A 9Wants to Know Investigation

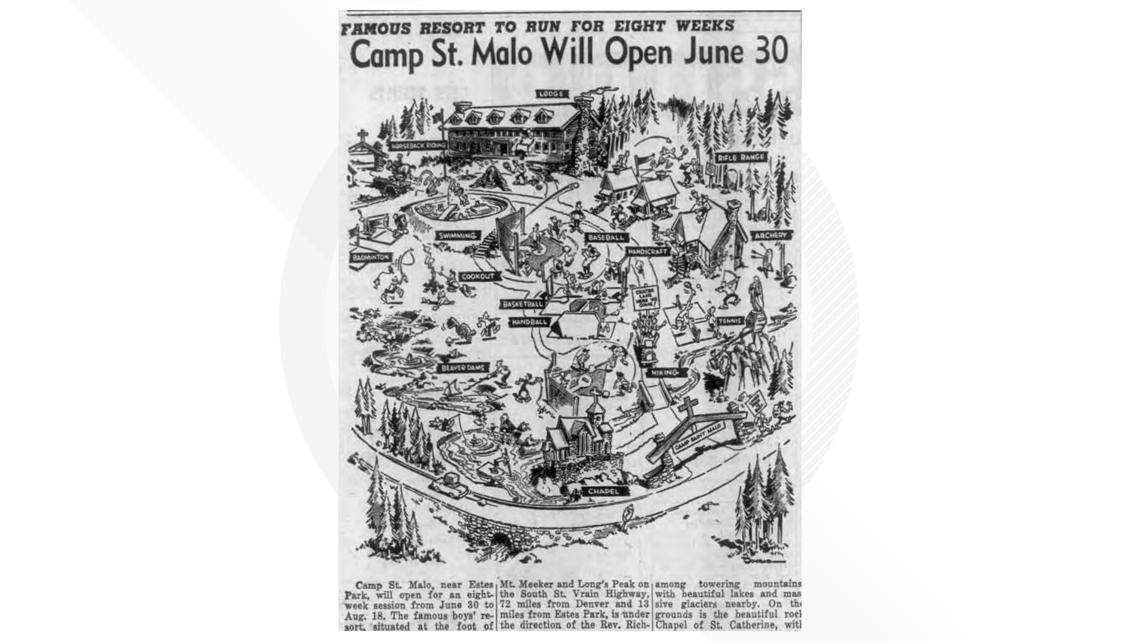

Camp St. Malo

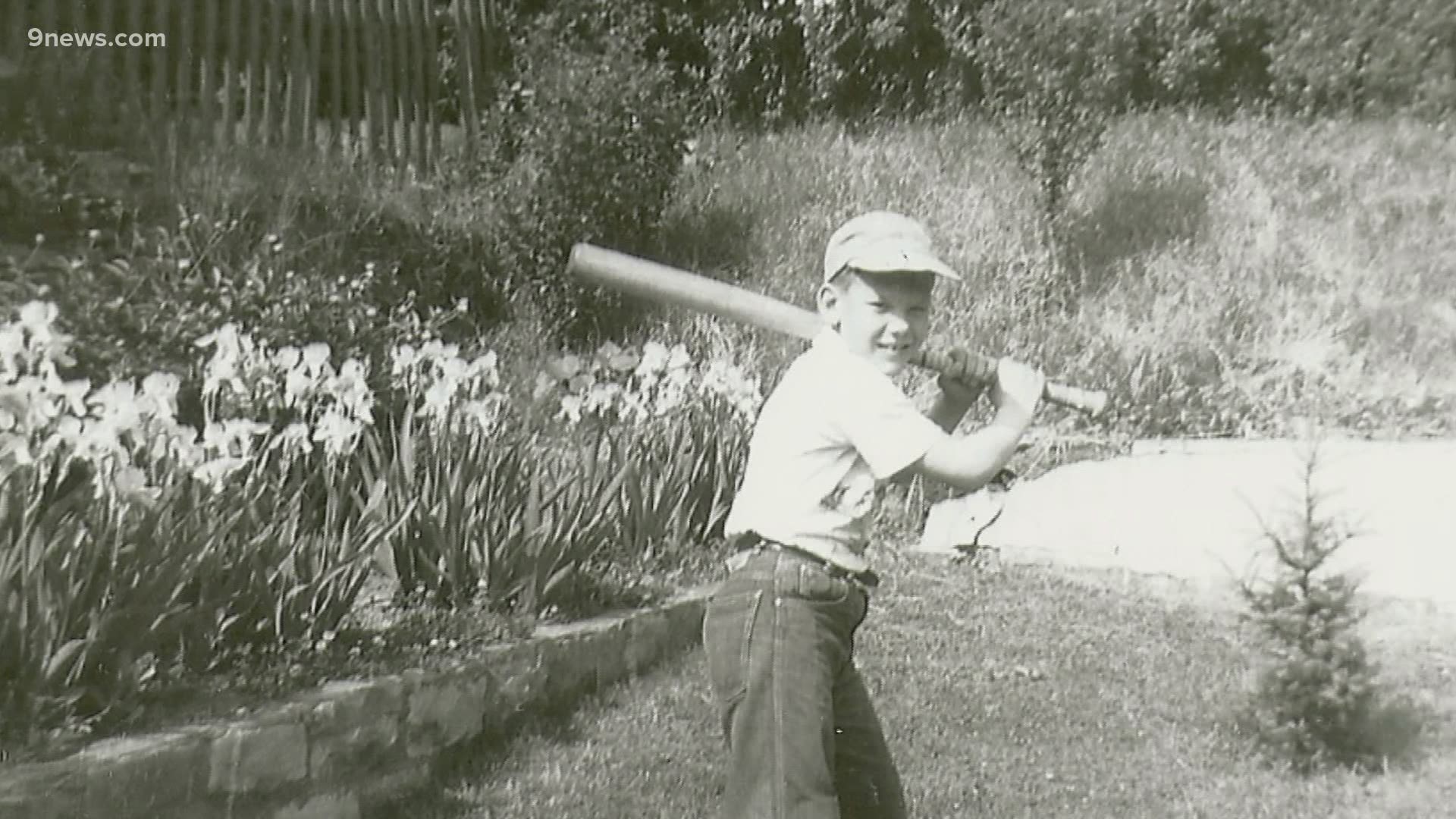

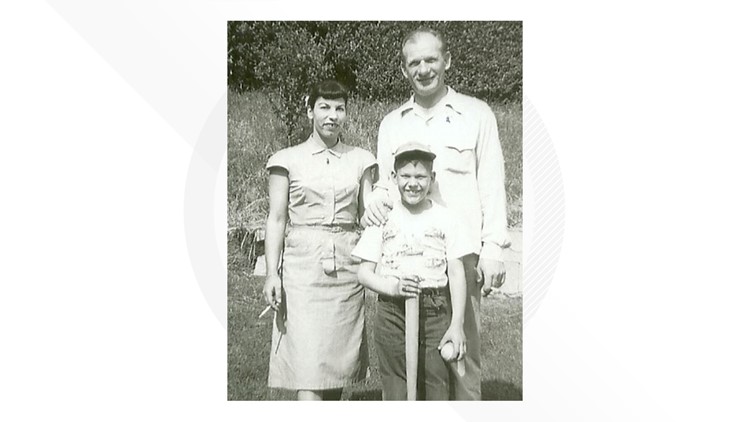

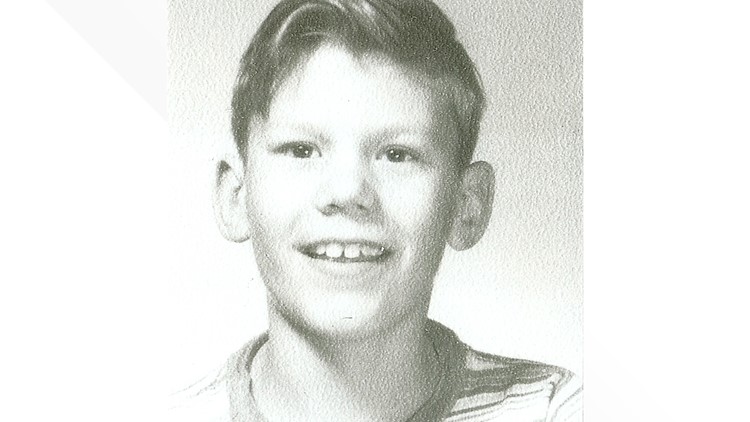

In the square, black-and-white snapshot, Bobby Bizup holds a toy pistol in his left hand, pointing it at the camera, a triangle of hair peeking from beneath his cap and pointing down his forehead.

There’s a mischievous grin sneaking across his face, just the barest hint of a gap in his teeth.

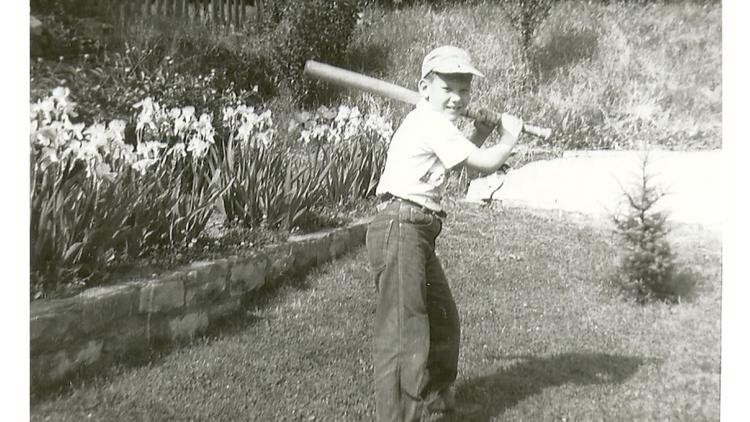

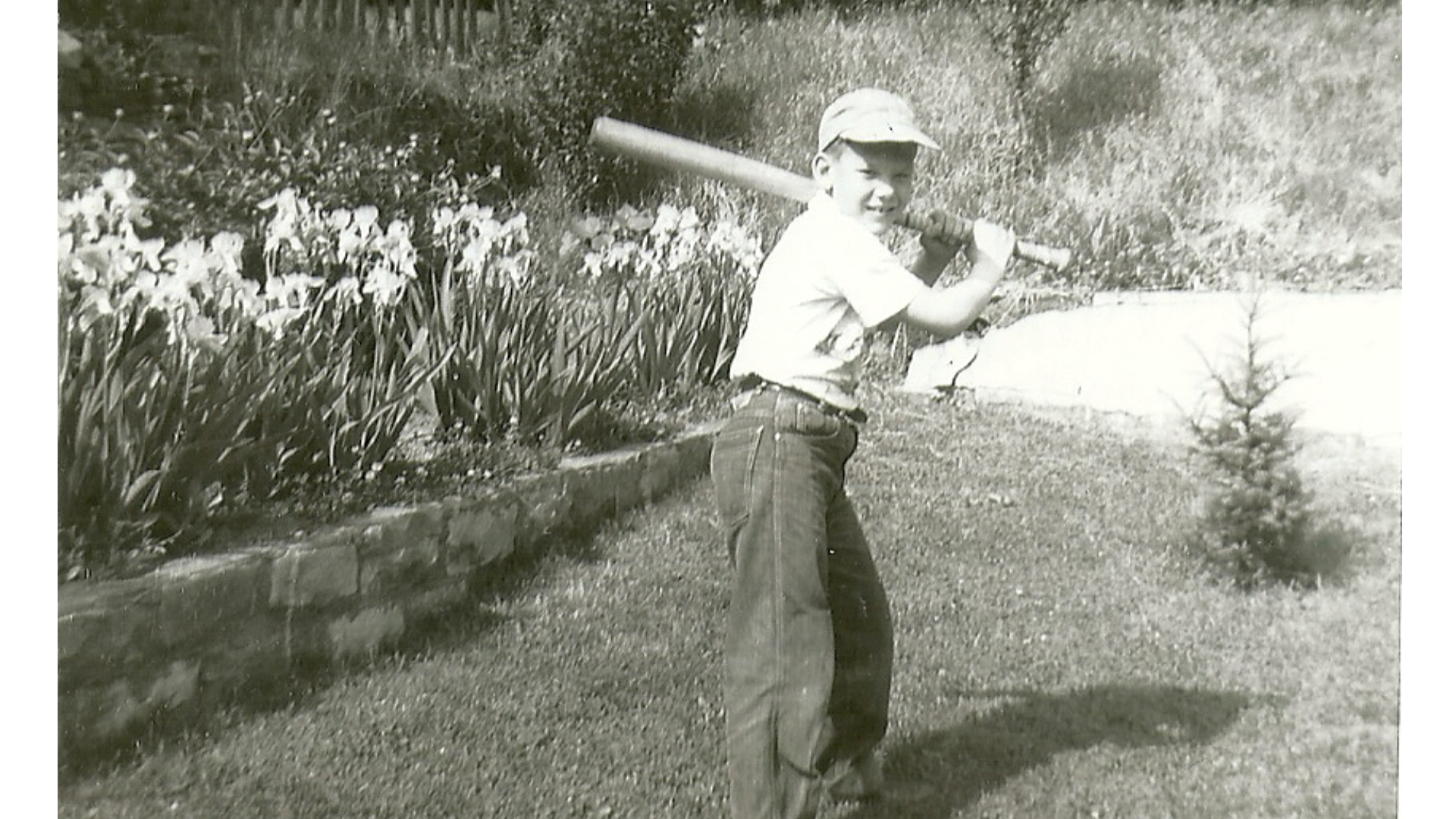

In another picture, Bobby cocks a bat above his left shoulder, ready to unleash a home-run swing on an imaginary pitch.

And the grin’s there again.

“He was always smiling,” said his cousin, Harriet Dudich.

Smiling, even though he was different in an era when that was a lot harder.

Born almost completely deaf, Bobby wore a hearing aid that didn’t do him much good. And when he spoke, few people besides his parents could understand him. He relied on sign language and lip-reading, and he seemed to shrug off the times that other kids teased him.

An only child, Bobby lived with his parents in a modest home on the edge of Denver’s Park Hill neighborhood. His father was a master sergeant stationed at Lowry Air Force Base. His mother didn’t work outside the home.

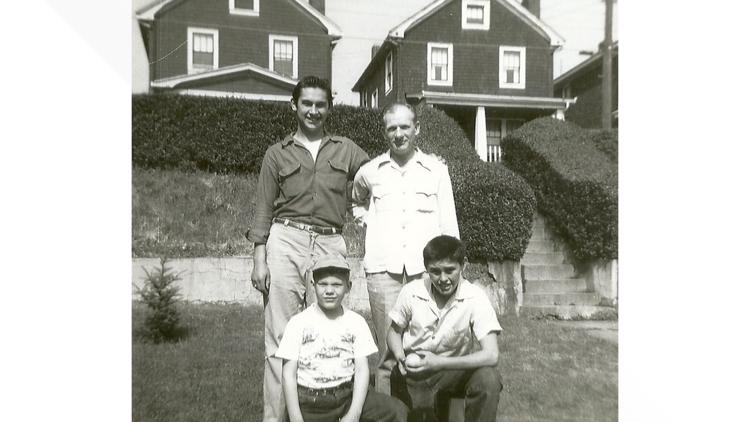

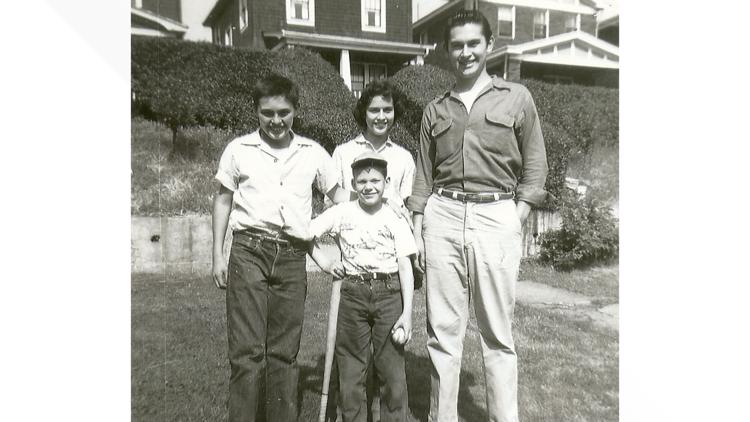

The photographs were taken in the summer of 1956 in Pittsburgh while Bobby and his parents visited relatives.

PHOTOS: Remembering Bobby Bizup

Bobby was 8 years old.

“He liked baseball,” Dudich said. “He had a bat and ball, and we had a pretty big front yard, and he used to go in the front yard and hit the ball around with my two brothers.

“They would play catch with him.”

They snapped nine photographs that day. Bobby with his parents. Bobby with his cousins. Bobby with his bat and ball.

In every one, he’s smiling.

“We had a very pleasant visit,” Dudich said.

She had no way of knowing it then, but it would be the last time she ever saw Bobby.

Mount Meeker’s barren summit looms to the west of Colorado Highway 7 between Allenspark and Estes Park.

High on the eastern face of the 13,911-foot peak, tiny Cabin Creek starts in the scree above treeline, cleaving a slash in the mountain as it tumbles downhill before meandering through trees as the earth flattens out on the eastern edge of Rocky Mountain National Park.

There, the crystal clear water trickles through gently rolling forest land before finally slipping past St. Catherine of Siena Chapel – the iconic “Chapel on the Rock” – ducking under Colorado Highway 7, and bending south.

The land, from the edge of the Rocky boundary to the chapel, is the home to the Catholic Church’s Camp St. Malo, and it’s hard to imagine a more beautiful place. A headline in the Denver Catholic Register in 1957 termed it “God’s Country” – and it’s easy to see why. Rugged peaks. Lush forests. Gentle streams.

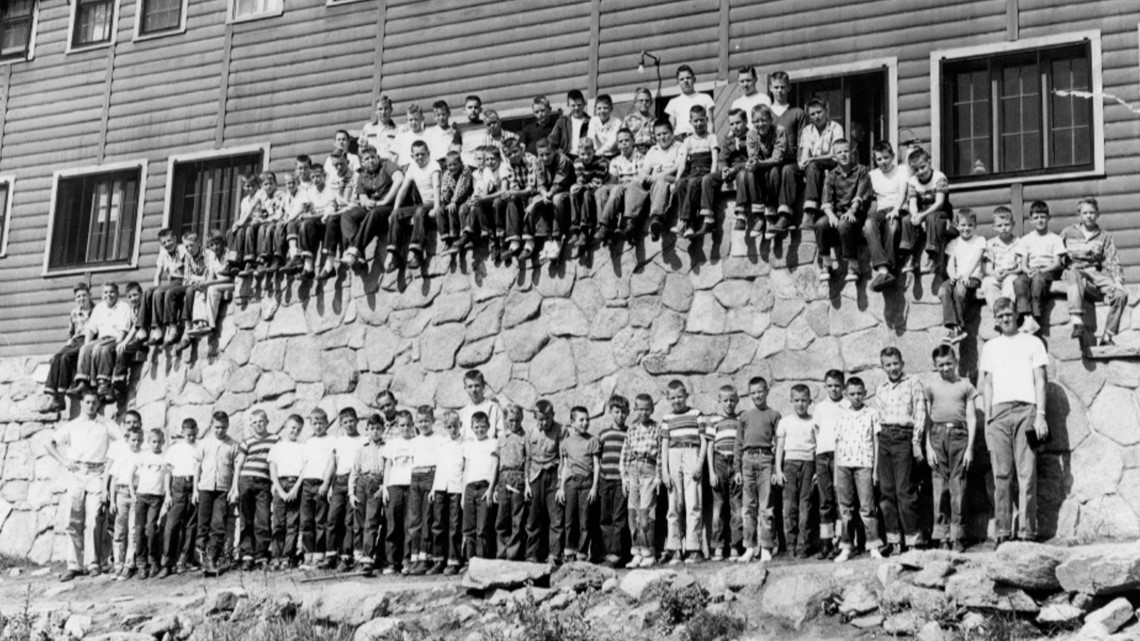

For generations, schoolboys spent summers here, swimming, shooting rifles, hiking, camping – their playful shouts carrying across the beaver ponds and through the pines.

Although it technically is still there, Camp St. Malo in many ways no longer exists.

The summer camp closed in the early 1980s, and the property was converted to a retreat – a place visited by Pope John Paul II during a break from World Youth Day.

But a 2011 fire destroyed its main building, and a flood two years later devastated its land. Today, the chapel continues to draw visitors almost daily, and a couple other buildings still stand.

But most of what was once here is now gone, existing only in memory for the thousands of children who visited over the years.

But for all those happy members, there’s also an uncomfortable reality: Camp St. Malo, it’s now clear, is a place with dark secrets.

And a place with a long-ago mystery about the disappearance of a deaf boy that’s never been thoroughly investigated.

Camp St. Malo in 2020

***

To understand Camp St. Malo as it once was, it’s important to understand its mystery.

Beginning in 1915, the Rev. Joseph Bosetti began taking members of the Cathedral High School choir and altar boys on camping trips on the land east of Mount Meeker.

By 1934, a scattering of buildings had been erected, and Camp St. Malo was born.

The chapel that greeted visitors went up the following year, and by the 1950s the camp was an extremely popular destination for Catholic boys in Colorado.

A boy could, almost literally, do anything he wanted.

A robust hiking and camping program meant twice-a-week treks to high peaks and glaciers in Rocky Mountain National Park. The sometimes-frigid swimming hole offered an exhilarating plunge. There were basketball, handball, tennis and badminton courts, as well as archery and rifle ranges and a craft shop where boys could construct model airplanes and take on other projects. Cabin Creek and area beaver ponds beckoned boys with their fishing rods.

Over the years, a well-established routine emerged.

The camp would open for six weeks each summer, usually starting in late June and stretching into August, welcoming boys ages nine to 16 for a week at a time. A crew of 75 to 90 boys – sometimes more – would arrive on a Sunday afternoon, play and hike and worship every day from dawn to dusk, and head home the following Sunday morning.

The Denver Catholic Register hyped the camp incessantly, with endless stories about the wholesome fun that awaited boys there.

“Big tasty hamburgers are a welcome sight to any growing boy; but when they are cooked outdoors over a big fire, where cool, mountain breezes can add more flavor to the burgers, then there is no holding them back,” one story gushed.

In 1958, parents were charged $30 for a fun-filled week, a few dollars more if they wanted to ride horses.

“It was a good experience,” said Richard Hiester, for whom Camp St. Malo was a family affair. “I have many memories.”

His uncle, the Rev. Richard Hiester, succeeded Bosetti as the camp’s director in the 1950s. The younger Hiester spent many weeks there over several years.

He remembers the blood spilling from his nose when he tried boxing. And how cold the swimming hole was.

And he remembers the hikes – like the treks up Twin Sisters that started in darkness.

“It was freezing cold – we’d be really cold – we hadn’t eaten yet,” the younger Hiester said. “We would have hiked all night because we would leave at two in the morning, so I remember that ritual and I remember being there a number of times for those Twin Sisters hikes.”

Once on top, his uncle would say mass as the sun rose.

There were also demanding feats of mountaineering for daring boys – sliding down a glacier and summiting Longs Peak – overseen by counselors who were seminarians studying for the priesthood.

“I remember, you know, climbing up or hiking up the northeast face of Longs Peak with those guys,” said Hiester, now a counselor living in New Mexico. “I just had a great admiration – you know they were these great counselors that could climb.”

He remembers one moment particularly well.

“On the northeast face, there was a cable route,” Hiester said. “And there was a hike between where you arrived at Chasm View and that cable, that you had to go up. And there was snow in that place.

“I don’t remember going up to the cables, climbing up, but I remember coming down. We had to slide, you know, to be caught by a counselor on the icefield between the cable and Chasm View. And I remember one kid started veering off – and he would have, he would have definitely gone off to his death.”

One of the counselors “splayed out” and grabbed the boy before he went over the side.

There’s another memory that stands out among so many others that have blurred together over the years. It occurred on a Friday in August 1958 – the last week the camp was open that summer.

It includes Bobby Bizup, making his second visit of the year to Camp St. Malo – after going three times the year before.

In 2019, the Colorado Attorney General reached an unprecedented agreement with the Archdiocese of Denver, the Diocese of Colorado Springs and the Diocese of Pueblo that allowed a former U.S. attorney to examine seven decades of church records and publicly expose priests who had been credibly accused of sexually abusing children.

The resulting report was unflinching – including detailed reports on 43 Colorado priests who molested at least 166 children between 1950 and 2019. It documented systemic failures in the church over the decades, from willfully covering up reports of sexual abuse to repeatedly failing to follow a state law requiring that those allegations be reported to police.

The report even stained Camp St. Malo, finding that its founder – Bosetti, a revered figure in the Archdiocese of Denver – repeatedly sexually abused a teenage boy in 1949 and 1950.

And it left open the possibility that there were others, noting that the victim had come forward in 2002 but that his report was not contained in Bosetti’s file. As a result, “we are therefore not confident that there was no other abuse by Bosetti or that the Denver Archdiocese did not know about it before Bosetti abused” the teen.

But it wasn’t just Bosetti.

Troyer’s report exposed sexual abuse on the grounds of Camp St. Malo in the 1950s and 1960s.

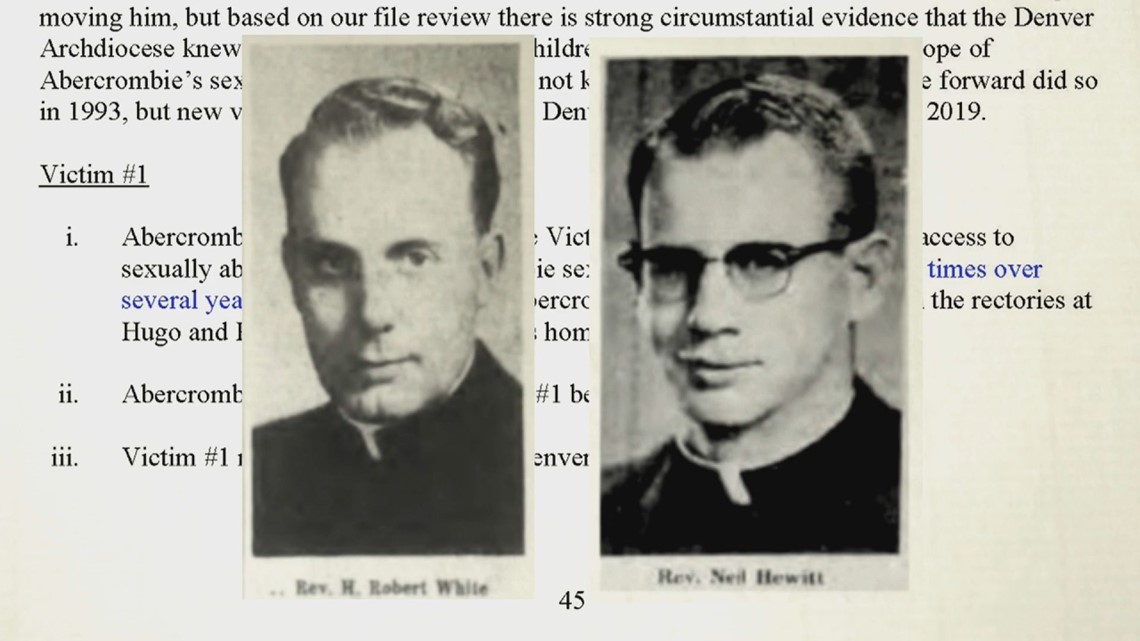

And it exposed abuse by two priests with long ties to the camp – men who served as counselors there for years while they were studying for the priesthood.

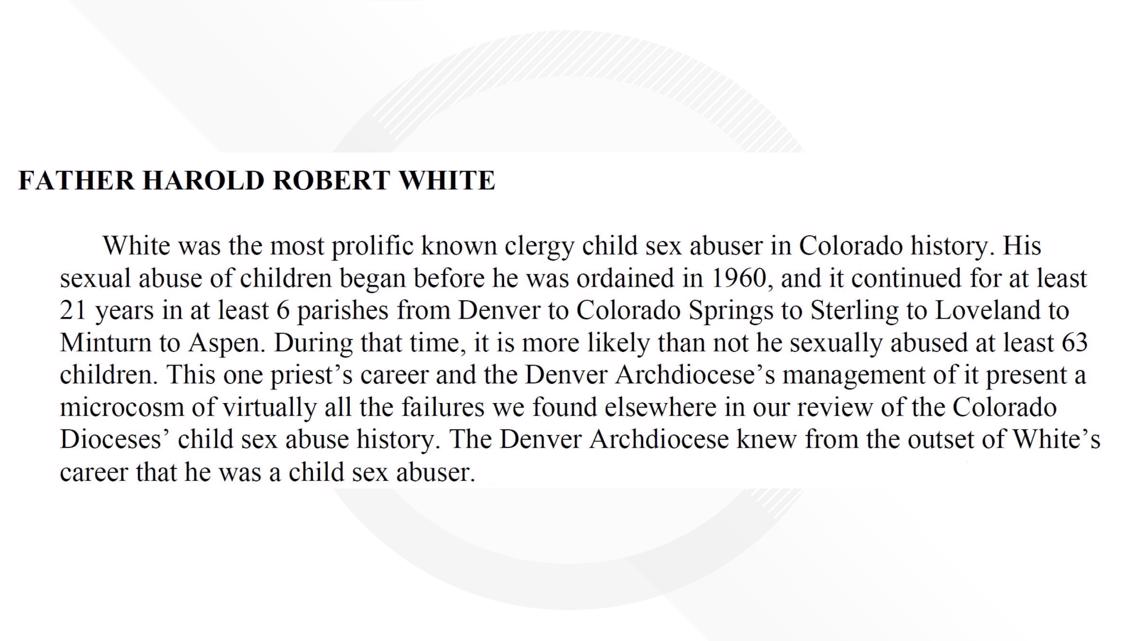

One was “the most prolific known clergy child sex abuser in Colorado history” – a man with at least 63 victims.

RELATED: Priest listed in sex abuse report was working at church camp in 1958 when deaf boy, 10, disappeared

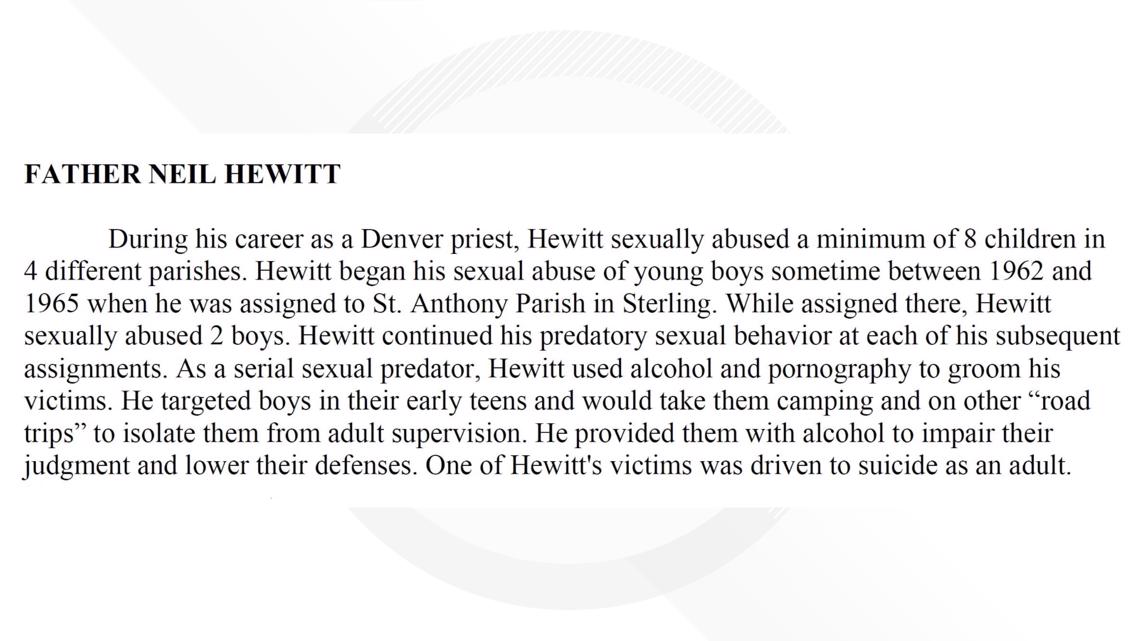

The other sexually abused at least eight victims in four different parishes, including one boy who later took his own life.

Both of them were seminarians serving as counselors at Camp St. Malo in the summer of 1958.

That was the year Bobby Bizup disappeared, never to be seen alive again.

Bobby Bizup vanishes

By 5 p.m. on Aug. 15, 1958, a sprinkling of rain had passed and the temperature had fallen from the afternoon high of 78 degrees down into the mid-60s – perfect fishing weather at Camp St. Malo north of Allenspark.

Cabin Creek – narrow enough in places to step across and little more than a foot deep – ran through the camp’s property, a great place for 10-year-old Bobby to hook a trout.

It was Bobby’s fifth week-long visit to the camp, and it made perfect sense that he’d be out along the stream, carrying an old ice cream carton full of worms and his fishing rod.

Eventually, a counselor named Terry Cowan let Bobby know he needed to gather up his things and head back to the main lodge.

“I pointed at my watch at 6 p.m. to remind him it was nearly time for supper,” the Denver Post quoted Cowan as saying. “He nodded that he understood.”

Almost completely deaf since birth, Bobby wore a hearing aid but couldn’t make out many sounds. He also had trouble speaking, relying on sign language and lip-reading to communicate. If he was flustered or upset, even that could be difficult.

Within an hour of that counselor's message, Bobby would be unaccounted for, the subject of an intensifying search in the woods around the camp operated by the Archdiocese of Denver.

A search that would prove fruitless – and a disappearance that would yield no answers for nearly a year.

By then, there wasn’t much of a question of what happened.

Bobby went fishing along the creek. Bobby failed to return to the lodge for supper and wandered off. Bobby got lost and couldn’t find his way back to camp.

More than six decades later, however, a new question has emerged: Is that the complete story of the disappearance of Bobby Bizup?

***

In the 1950s, Camp St. Malo had a reputation as a mythical place – where boys worshipped and learned wholesome life lessons in the ruggedly beautiful Colorado mountains between Estes Park and Allenspark, where a counseling staff made up of young seminarians studying for the priesthood oversaw all the activities.

During their week-long visits, campers worshiped at St. Catherine of Siena Chapel – the “chapel on the rock” that greeted visitors turning onto camp property from Colorado Highway 7. They hiked and climbed and camped in neighboring Rocky Mountain National Park. They sat around bonfires and sang camp songs to the strum of a banjo as darkness descended in the evening.

Today, it’s clear that’s an incomplete picture.

The Catholic Church’s reckoning for the sexual abuse by some of its priests hit Colorado a year ago when state Attorney General Phil Weiser released a damning report showing that at least 43 members of the clergy had molested at least 166 children since 1950.

At least three of those children were sexually abused at Camp St. Malo in the 1950s and 1960s.

The report, written by former U.S. Attorney Bob Troyer after a review that included examination of internal church documents, laid out in disturbing detail the acts of the abusive priests.

Among them were Harold Robert White, which the report described as “the most prolific known clergy child sex abuser in Colorado history,” and Neil Hewitt, who it said worked to isolate his victims from their parents, often on camping trips.

One of Hewitt’s victims, the report noted, took his own life years later, leaving behind a letter where he wrote extensively of the abuse he suffered.

In 1958, the year Bobby went missing, White and Hewitt were both seminarians, working as counselors at Camp St. Malo.

***

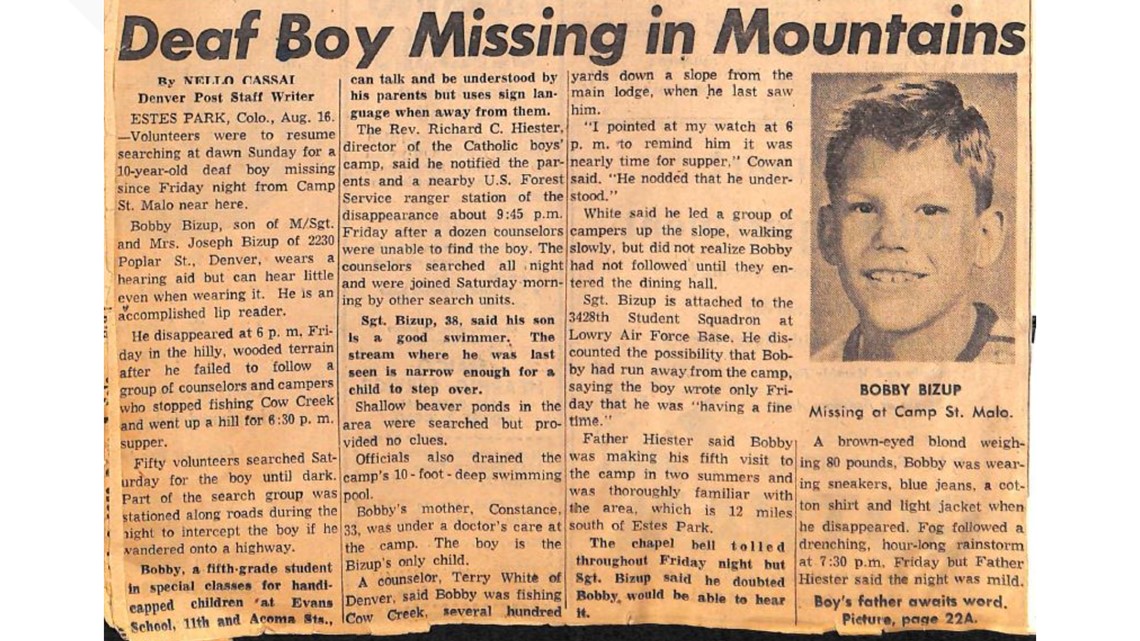

The disappearance of Bobby Bizup was big news, hitting the front pages of The Denver Post and Rocky Mountain News, the competing papers settling on remarkably similar headlines.

Denver Boy Lost in Mountains

Deaf Boy Missing in Mountains

The boy’s parents, Joe and Connie Bizup, arrived at camp the day after he vanished.

His mother could hardly stand the strain – she was reported to be under a doctor’s care, unable to eat.

Bobby was the couple’s only child.

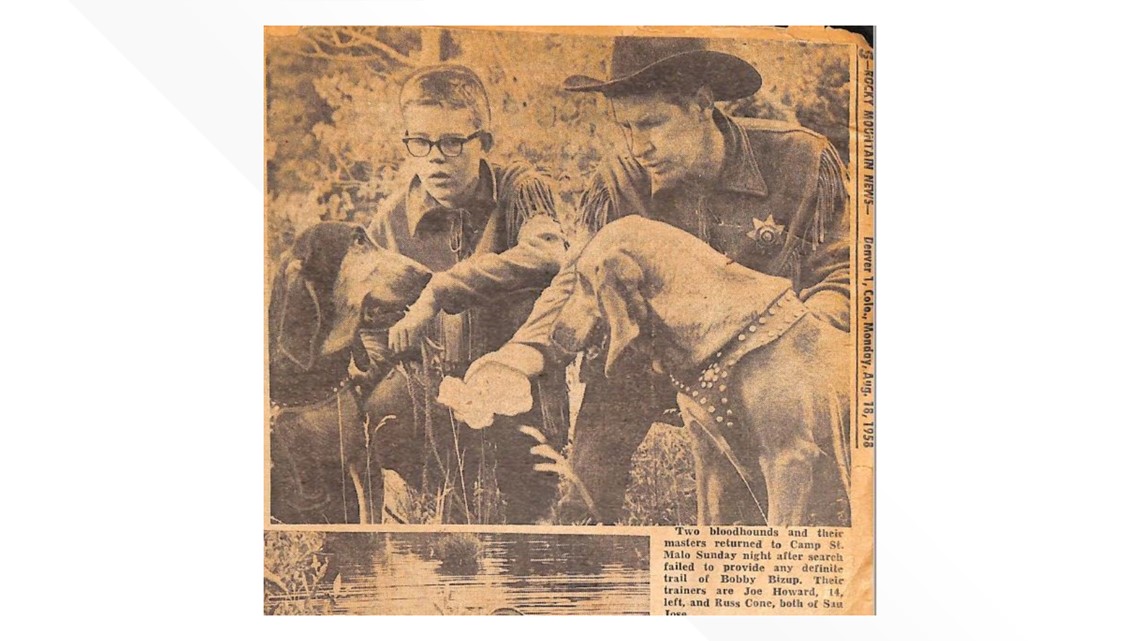

Within days, the searchers had grown to 500 strong. Airmen from Lowry – where Joe Bizup was stationed – showed up. So did volunteers from the Colorado Civil Air Patrol and search and rescue squads around the area. A California man with two bloodhounds flew to Colorado to help. Someone even contacted an Indian tracker.

Crews fanned out, walking the woods, patrolling the roads, searching empty cabins up and down the valley. Skin divers searched nearby waterways. Camp leaders dynamited the beaver dams near the camp and drained the 10-foot-deep swimming hole, thinking Bobby might have drowned.

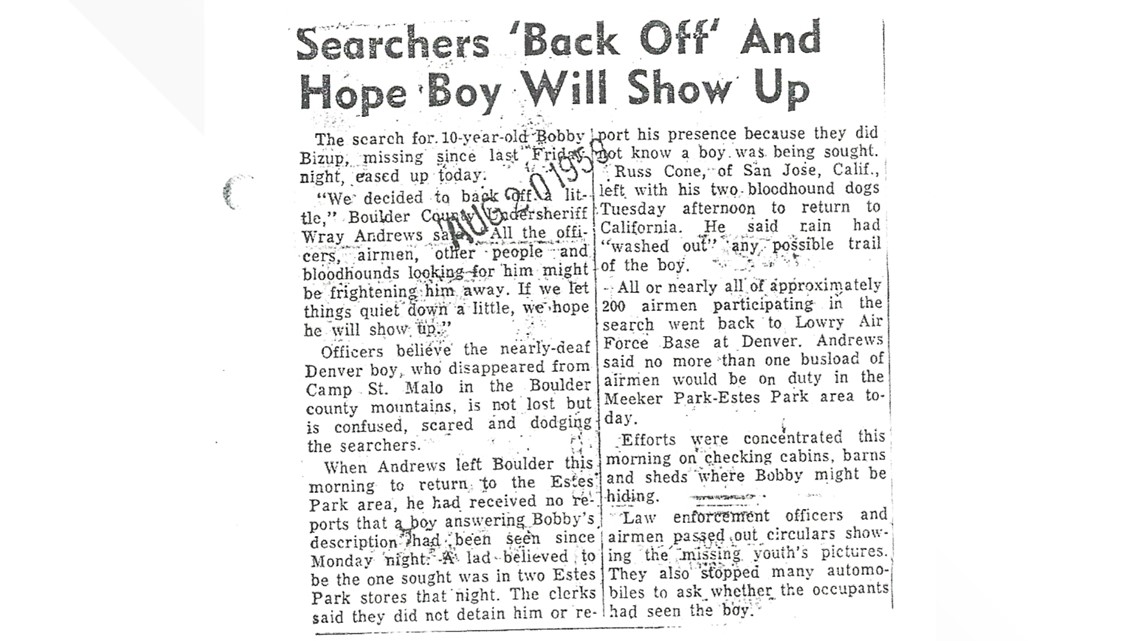

On the third day, authorities started to get reports that a boy matching Bobby’s description was seen in Estes Park – a boy who was wearing a hearing aid. Almost immediately, search teams headed there, and it prompted speculation that Bobby had run off deliberately and was avoiding the people trying to find him.

Even his parents joined in that belief.

“We think he was frightened and he is scared now and is hiding,” Connie Bizup told a Rocky Mountain News reporter. “Perhaps he thinks he will be punished. We don’t know what he is thinking.”

The Estes Park Trail paid for thousands of leaflets containing a message written to Bobby by his parents, and a pilot flew over the camp and the surrounding forest and dropped them.

MOTHER AND FATHER LOVE YOU.

WE NEED YOU.

MOTHER IS SICK.

SHE NEEDS YOU AT HOME.

WE LOVE YOU.

But then a man who’d been vacationing in Estes Park called police. His son looked like Bobby – right down to the hearing aid – and was in the mountain town the day several people reported seeing the deaf boy.

And that wasn’t the only confusion surrounding the search.

Bobby was described in some accounts as fishing by himself and in others as being with a group of boys from the camp.

One story said his fishing pole and worms had been found on a hillside near the camp. Another said his cardboard worm box was a half-mile from camp.

Still, others got the name of the creek wrong.

Eventually, the effort to find Bobby ran its course.

“We are calling off the search,” Father Richard Hiester, the camp’s director, told the Boulder Daily Camera for a story published 10 days after the disappearance. “We’ve exhausted all possibilities.”

Plans were made to keep a few people at the camp in the hope that Bobby might still return, but he never did.

***

The 1959 camping season at St. Malo opened on Sunday, June 28.

Neil Hewitt was back for his fourth season as a counselor.

Five days later, Hewitt and two other counselors led a group of boys west from the camp along Cabin Creek, crossed the boundary into Rocky Mountain National Park, and climbed high up the eastern face of Mount Meeker.

They were around 11,000 feet in elevation, in a place where the trees give way to the rocky scree of the mountain’s upper reaches and Camp St. Malo is clearly visible in the valley below, when Hewitt caught sight of a torn piece of clothing.

That led to the discovery of a bone.

A doctor later concluded the bone was that of a young boy. The remains of Bobby Bizup, it appeared, had been found.

The park service organized a formal search.

“We talked before we headed out,” said Larry Collins, who led a group tasked with returning to the spot where the clothing and bone had been located and recovering whatever they found. “I said to my men, 'this is very serious fellows – no clowning around; no jokes. We need to do the very best job we can.'”

The group climbed up Mount Meeker and went to work.

“We strung it all off with strings, and then we ran strings across,” Collins said. “Then we would search back and forth between strings.

By the end of the day, they’d found more bones and 20 additional pieces of clothing – scraps of a shirt, pants and shoes – as well as a red ball cap and a Zenith hearing aid battery.

There was no doubt. Bobby had been found.

His parents were in Pittsburgh visiting relatives when the discovery was made.

“They weren’t the same,” said Harriet Dudich, Bobby’s cousin.

She rode back to Denver with her aunt and uncle for a visit.

“No sooner had we pulled up in front of the house, the phone was ringing off the hook, and my uncle went in and he answered the phone,” she said. “That’s when he was told that they had found Bobby’s remains.

“My aunt – she just collapsed. She was very distraught.”

Boulder’s coroner concluded the cause of Bobby’s death was “probably from exhaustion and exposure.”

Bobby’s parents buried him at Fort Logan National Cemetery.

***

For six decades, not many people thought much about Bobby Bizup – and those who did believed he’d simply gotten lost and died the elements.

A tragic accident.

“Nobody quite knew what happened,” Dudich said. “We just thought that since he couldn’t speak and couldn’t hear, he got lost in the woods. The whole family believed that all these years.”

His family didn’t blame the camp, or the counselors.

“The people up there did everything they could to take care of Bobby,” Joe Bizup told The Denver Post. “They take good care of all the boys there and this incident certainly isn’t their fault.”

There was apparently no police investigation – although the sheriff’s departments in both Boulder and Larimer counties were heavily involved in the search, no reports could be located at either agency.

INTERACTIVE TIMELINE: The disappearance of Bobby Bizup

The Archdiocese of Denver has no files on Bobby’s disappearance, according to spokesman Mark Haas.

“This tragic situation occurred 62 years ago and no one currently working for the archdiocese has any direct knowledge of it,” Haas said in a statement. “We are not in a position to respond to speculation about something that happened six decades ago.”

But others have speculated – and raised questions – about whether something more sinister happened the day Bobby went missing, given that two of the counselors there that summer have now been branded serial child sex abusers by the former U.S. attorney's report.

“It just, to me, is a red flag,” said Michael Smilanic, who was molested by Neil Hewitt in the 1960s. “It's a scary coincidence to me.”

“Whew – it’s kind of scary,” said Donna Ballentine. Hewitt molested her cousin, Stuart Saucke, in the 1960s. He later took his own life.

A 9Wants to Know investigation into clergy child sexual abuse in Colorado led a reporter to a mobile home park on the outskirts of Tucson in April 2019. It was six months before the release of the report showing that Hewitt had been credibly accused of molesting multiple children.

Hewitt, who left the priesthood in 1980 and married, answered the door and admitted to sexually abusing Smilanic and Saucke.

During a conversation that lasted more than 30 minutes, Hewitt was asked about Bobby Bizup.

> Video below: 9Wants to Know Reporter Kevin Vaughan speaks to Neil Hewitt.

“What I remember,” Hewitt said, “was … I was running, I guess you’d call it, the snack bar at the time at St. Malo.”

Bobby wanted to buy candy. Hewitt said he thought Bobby’d had too many sweets.

“And I said, no, I don’t think we ought to," Hewitt said. "And so he, he took off.”

And then Hewitt denied wrongdoing – even though he hadn’t been asked.

“I did not do anything to him, except not give him more candy,” Hewitt said.

A new investigation

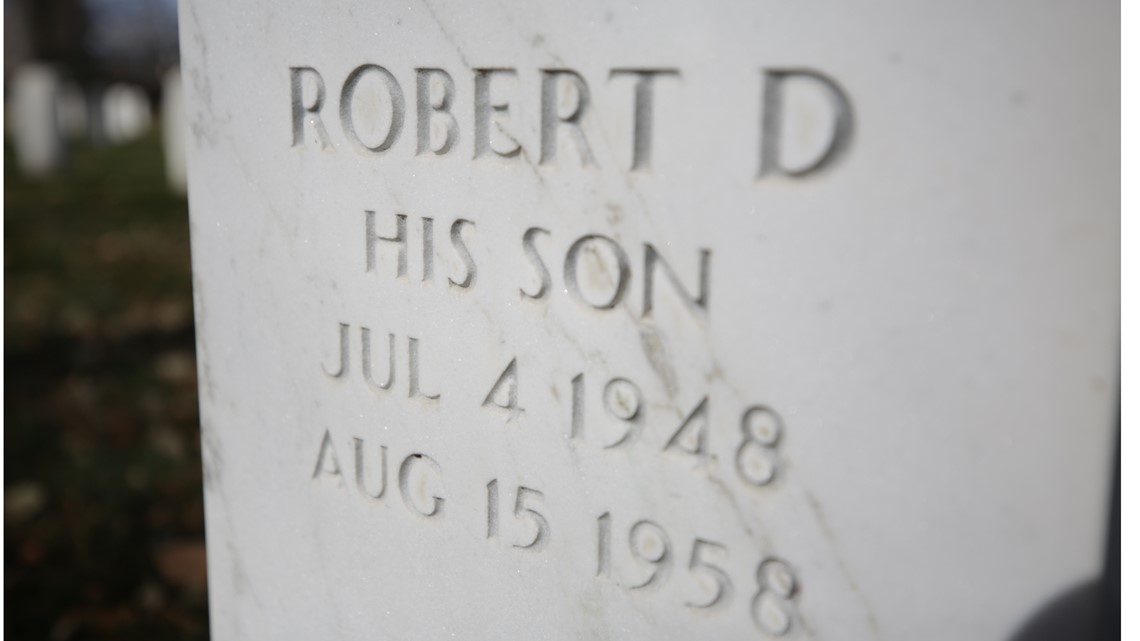

In the northwest corner of Fort Logan National Cemetery, just a few steps from an entrance gate along busy Sheridan Boulevard, the morning sun brushes across a marble headstone, casting shadows in the inscription on the back of the marker that bring the letters and numbers into sharp relief.

ROBERT D

HIS SON

JUL 4 1948

AUG 15 1958

It’s the final resting place of Bobby Bizup, a 10-year-old deaf boy who vanished in 1958 from the Catholic Church’s Camp St. Malo near Allenspark, in Boulder County. He’s buried with his father, an Air Force veteran.

Bobby’s disappearance, and the discovery of his remains nearly a year later high on the east face of Mount Meeker, elicited extensive news coverage. But in the end, no one in a position of authority thought it could be anything other than a tragic accident – a boy who got lost in the woods and succumbed in the rugged country of Rocky Mountain National Park.

Bobby was an only child, and as the decades passed he was remembered by an ever-dwindling number of people – mostly cousins living in other parts of the country.

But revelations the past two years about sexual abuse by Catholic clergy sparked a 9Wants to Know examination of the case that raised new questions about Bobby’s disappearance and death – and has led to calls for a cold case investigation.

Two of the counselors at the camp that summer were seminarians studying for the priesthood who went on to be serial child sex abusers. One of those men was among the last to see Bobby and the one who discovered his remains – and he now tells a story about an interaction he had with Bobby shortly before the boy’s disappearance that was never publicly revealed back in 1958.

A boy at St. Malo with Bobby saw him extremely upset before he vanished – a story that mirrors what staff members at the camp told park rangers.

Two of the men involved in the recovery of Bobby’s remains now question the idea that he simply got lost.

And leaders at the camp did not report the discovery of Bobby’s remains to authorities until three days after they were found, an unexplained gap that troubles a former prosecutor who looked at the case.

All of it feeds into this question: Could Bobby Bizup’s death have been result of foul play?

“We just assumed that he went up so far that maybe he froze to death, or he ran out of food and starved to death, or an animal may have taken his life,” said Larry Collins, a 35-year seasonal worker at Rocky Mountain National Park who led the crew tasked with recovering the boy’s remains.

Today?

“Now, as time goes on, and we think back on it, he was running – he was running away,” Collins said. “He was trying to get away from something. And so the possibility of foul play? Certainly is a possibility.”

“It’s extremely suspicious,” said Rich Orman, a criminal prosecutor in Colorado for more than two decades. “There’s no proof of anything. There’s a lot of reasons to be suspicious of things.”

***

In 2019, when former priest Neil Hewitt acknowledged that he’d interacted with Bobby Bizup at a Camp St. Malo snack bar shortly before the boy vanished, he was, in effect, identifying himself as one of the last to see the boy.

But he apparently wasn’t the very last.

A scene described by Richard Hiester, who was camping at St. Malo that week, fills in more of the picture of the time before the boy dropped out of sight.

“There was the chapel – this rock chapel as you drove in,” Hiester said. “And then you went a ways, across from the beaver ponds, there was a large house that was kind of the gathering hall for the larger occasions.”

Hiester was 11 years old that summer. And he was very familiar with the St. Malo – his uncle, the Rev. Richard Hiester, was the camp’s director.

“We were all gathered there as a group, and I really don’t know what took place except that at some point this kid came running past me, kind of pushed me out of the way,” Hiester said. “He was loud, and what he was saying was unintelligible to me.

“And then he ran out that front door.”

At the time, Hiester did not know the boy’s name. He now knows it was Bobby Bizup.

“I think I remember asking, well who was that, and what was that about?” he recalled. “And somebody saying that was that deaf kid.”

It’s been a long time since that moment, but Hiester believes the scene unfolded on Aug. 15, 1958.

That was the day Bobby went missing – and Hiester believes what he saw was “immediately before he disappeared.”

Although he doesn’t know what led up the outburst, he is sure of one thing: Something happened that really upset the boy.

“He was really angry,” Hiester said. “When he left, he was really angry, and pushing and got out of that hall.”

That sequence of events was confirmed by Roger Contor, at the time a sub-district ranger in Rocky Mountain National Park.

Contor was also involved in the recovery of Bobby’s remains – and he talked to staff members at the camp who also told him a version of the same story: That something had severely upset the boy before he went missing.

“I was struck by the, I’d say, unanimity of all the people we talked to,” Contor said. “Everybody said this was a very troubled young man. … I asked well was he upset, was he angry, was he embarrassed, was he hurt, and the answer is all of the above.

“So he was a very upset and troubled person. I think we can accept that’s second-hand information, but it’s good still. “

The question that can’t be answered – at least now – is what happened to leave the boy so out of sorts?

***

Beginning in 1954, Larry Collins spent summers prowling Rocky Mountain National Park on one long search-and-destroy mission, looking for gooseberry and currant bushes within 100 yards of groves of white pine trees.

Those bushes hosted a fungus, known as blister rust, that attacked the pines – often killing seedlings and young trees.

“We would fly the park and we could spot these groves of white pine,” Collins said. “And we’d do that every summer.”

Then he and his men would set out, trekking through the park’s sometimes unforgiving terrain to find and eradicate the bushes feeding the fungus.

By 1958, the work was largely finished.

So after the remains of Bobby Bizup were discovered in a ravine near treeline on Mount Meeker, it was natural that Collins and his men would be assigned to climb up the east face on a mission to recover everything they could find.

Collins spent 35 years as a seasonal employee at the park, and eventually was involved in countless rescue and recovery missions.

Many of them have blurred together, but today the case of Bobby Bizup remains clear in his mind.

Not just because it involved a vulnerable 10-year-old boy, but also because he now questions the original narrative – that Bobby simply wandered off and got lost.

He bases that question on this simple fact: The place where Bobby was found was about three miles up the side of Mount Meeker from Camp St. Malo – a rise of about 2,500 feet.

And he’d never seen anyone lost in the park who just kept going uphill.

“No,” he said, sitting on the edge of the St. Malo property, gazing up the east side of Meeker. “As you look up at that mountain, he could look back and see the camp. He could always tell where he was. Now, if he was lost, he would have been lost in the trees. But once he got above treeline, he could look back in and see the church. You could see the camp.”

News stories at the time noted as much – that the camp was visible from the area where the remains were found.

The day Bobby went missing, he was near the end of his fifth week-long trip to St. Malo over two summers – meaning he’d spent more than 30 days at the camp.

“I believe he was well-acquainted with the area, and I doubt seriously that he would have gotten lost,” Collins said. “I think he knew exactly where he was.”

Collins’ thoughts dovetail with those of Contor, who at the time was a sub-district ranger at Rocky and another of those on the recovery mission.

“You don’t go there,” Contor said after he was asked whether he thought the location of Bobby’s remains suggested he was simply lost. “You want to go there to get away from something.

“Not just that – the whole location and the setting just said, he wanted out and he wanted to stay out. It wasn’t a pleasure trip, at all. This is tough country.”

“He wanted to get away from Camp St. Malo,” said Contor, whose distinguished career in the park service included a stint as superintendent of Olympia National Park and as the agency’s regional director in Alaska. “He didn’t want to go anywhere else or meet with any other people.”

***

After Bobby Bizup’s remains were discovered, the news was kept quiet for six days, for a simple reason: The boy’s parents were traveling and could not be reached.

But there’s another aspect of that development that’s never been explained.

According to accounts in five different newspapers – some based on different sources and on interviews conducted at different times – Neil Hewitt and the other hikers came upon Bobby Bizup’s remains on July 3, 1959.

It was a Friday.

But the Rev. Hiester, the camp’s director, did not report the discovery until July 6, the following Monday.

Orman, the former criminal prosecutor, found the three-day wait concerning.

“You have this delay of report,” he said after reviewing the results of the 9Wants to Know investigation, “combined with a large organization with a history of some members abusing children and the organization attempting to cover it up.”

Orman was also bothered by Hewitt’s connection to the case, and by the fact that the story about the dispute over candy apparently was never previously reported.

But the delay – especially when the ranger station where Hewitt made the report was only a little over two miles from the camp – led him to conclude that there might have been a lot more to Bobby Bizup’s disappearance than a boy getting lost in the woods.

“To me, you can’t look at that delay and think there wasn’t a reason for it,” Orman said. “It just doesn’t happen on its own, and the reason for that delay – I’m not saying it’s incriminating, per se – but it’s extremely suspicious.”

***

Back in 1958 and 1959, the idea that Bobby’s disappearance and death could be anything other than an accident apparently wasn’t entertained.

The investigation that was done was focused on two things. The first year the effort was focused on finding Bobby, the second on confirming the remains found on Mount Meeker were his.

“We did find lots of evidence,” Contor said. “By finding quite a few bones and finding the battery case of his hearing aid, it gave a positive identification that this was indeed Bobby Bizup.

“Up until that time, we wouldn’t have been sure – this is before DNA.”

Today, if Orman were a prosecutor with jurisdiction over the disappearance and death of Bobby Bizup, he would approach it as a cold case and call for a fresh investigation – something that 9Wants to Know has confirmed is now going to happen.

The National Park Service’s Investigative Services Branch has opened an investigation into the case, multiple sources confirmed.

It’s likely to be a challenging task – many potential witnesses are no longer living, and it appears that very few documents exist detailing what happened.

But it could also once and for all answer a question that wasn’t asked for more than six decades – what happened to Bobby Bizup?

“I really hope that there is justice for Bobby,” said Dudich, his cousin. “He was denied his life.”

Sources

The account of the disappearance and death of Bobby Bizup and sexual abuse by Catholic clergy in Colorado is based on the following sources:

- Newspaper articles from The Denver Post, Rocky Mountain News, Boulder Daily Camera, Fort Collins Coloradoan, Greeley Tribune, Denver Catholic Register, and the Associated Press.

- Interviews with Harriet Dudich, Bobby Bizup’s cousin; former Catholic priest Neil Hewitt; Donna Ballantine, whose cousin was molested by Hewitt; Michael Smilanic, who was molested by Hewitt; retired National Park Service employees Larry Collins and Roger Contor, who were involved in the recovery of Bobby Bizup’s remains; Mike Bunce and Richard Hiester, who were campers at St. Malo in 1958; Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser; former U.S. Attorney Bob Troyer; former prosecutor Rich Orman; former Colorado Civil Air Patrol members Joe Ramstetter, Frank VanPelt, and Raybert Sowl; and Dave Lewis, who helped coordinate the original search for Bobby Bizup.

- Rocky Mountain National Park Superintendent James V. Lloyd’s undated report of the disappearance of Bobby Bizup.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration weather records for the Allenspark area.

- Roman Catholic Clergy Sexual Abuse of Children in Colorado from 1950 to 2019, a report authored by former U.S. Attorney Bob Troyer under an agreement between the Colorado Attorney General and the Archdiocese of Denver, the Diocese of Colorado Springs, and the Diocese of Pueblo.

- Archdiocese of Denver personnel records for Harold Robert White, publicly released pursuant to litigation.

- Fort Logan National Cemetery record of interment for Bobby Bizup.

- Information provided by the Boulder County Coroner’s Office; the Boulder County Sheriff’s Department; and the Larimer County Sheriff’s Department.

- Scrapbooks compiled by the Rev. Richard Hiester, director of Camp St. Malo at the time Bobby Bizup vanished, available at the Archdiocese of Denver’s website.

Contact 9Wants to Know investigator Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story: kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: What happened to Bobby Bizup?