Family fights 3 years for custody of their own child

Allegations of “Promises Made” are some of the questions surrounding how the Washington County Department of Human Services handled a child custody case.

“July 8th, 2019 was the day I found out,” Alicia Johansen said.

It was that day she and Fred Thornton found out they were having a baby. But becoming parents wasn’t part of their plans and at the time they were both regularly using meth.

“Because I was using I didn't have periods and I didn't think that I could get pregnant, which was dumb, but I just assumed, no, it can't happen and it won't happen. And it hasn't happened until like, one day, I was like, I bet that's what this is,” Johansen said.

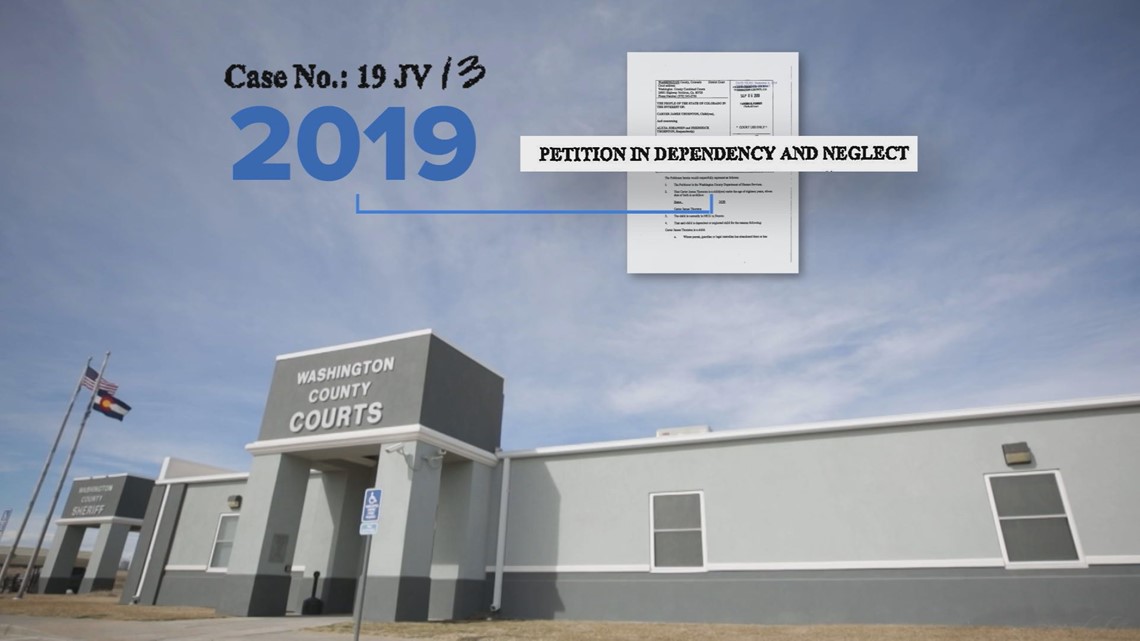

An unexpected pregnancy The beginning of case number 19JV13

She was already six months along and hadn’t received any prenatal care. A month later, on Aug. 6, 2019, in the early morning Johnsen had terrible pain in her stomach, a neighbor took her to the hospital in Brush.

“They decided I had preeclampsia and I needed to deliver that day,” she recalled.

She was flown by helicopter to Denver, underwent an emergency C-section, and two months early, her son Carter James Thornton was born.

“There was a nurse that came in and she said, I need to know what substances or whatever she called it that you were on. What have you been using? Have you been drinking?”

Johansen told the nurse about her drug use. Tests showed there were drugs present in the placenta.

Her son Carter stayed in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) for two months and was then released into the care of a foster family. The couple was relieved that their child was being taken care of.

“I told them, thank you so much. I really appreciate what they were doing,” Johansen said.

That is how court case number 19JV13 began. The Dependency and Neglect case was opened by the Washington County Department of Human Services.

Getting things in order 'She made that commitment. She was a rockstar.'

“I just felt like I needed to get a few things in order.”

Johansen and her partner Thornton knew that they had to get clean, and a treatment plan ordered by the court laid out the steps they needed to complete for Carter to be returned to them.

These included:

- Staying sober

- Obtaining stable employment

- Attending all scheduled visitations with Carter

According to court documents, the estimated completion date for their plan was March 5, 2020.

“I knew that I was going to turn around because I had to. It was not an option. We did not slip up one time,” Johansen said.

She didn’t feel like they were an exception but acknowledged it was an achievement to stay sober.

“The goal is once the parents are stable in their sobriety and it's safe for the children or the child to go home, you start working toward that,” said Attorney Tricia Matuszczak who was assigned to help Johansen navigate the legal process.

“It took Alicia a couple of months, three months to turn it around. And once she made that commitment, she was a rock star,” Matuszczak said. “She was at every visit. She went to every therapy appointment. She did every UA [urine analysis] and they were consistently clean. Anything that the department asked of her, she did.”

Matuszczak has represented parents for 20 years and said few clients have made such a dramatic turnaround.

As Carter was growing from baby to toddler Thornton and Johansen had 30-minute visits twice a week with their son. They started to become concerned when their visitation time wasn’t increasing.

“I just had this feeling like it [wasn't right] but I'm doing everything. They know that I'm doing everything. Why isn't it worked out yet?”

Foster parent intervention 'It was hard not to think sometimes, should I give up?'

In June 2020, Johansen submitted a clean hair follicle test to the court, to prove she had gone more than three months without drug use. Three days later Carter’s foster parents filed a Motion to Intervene in the case. Under current Colorado law, foster parents can file that motion once a child has been in their care for three months and if they have information concerning the care or protection of the child.

“The hoops that these parents had to jump through … none of that would have happened without foster parent intervention,” said Melanie Jordan. She is the Case Strategy Director for the Colorado Office of Respondent Parents’ Counsel (ORPC), a state-funded agency that helps parents get back their parental rights.

“Foster parents come into a case as full parties. They are able to file motions, call witnesses, cross-examine witnesses, and participate fully in all aspects of the case,” Jordan said.

According to data provided by the ORPC foster parent intervention has increased in Colorado in the past decade. In 2020, 10% of Dependency and Neglect cases had Intervenors. When foster parents intervene, the chance of reunification decreases from 62% to 22% for the birth parents.

Once the foster parents intervened in case 19JV13, the court started hearing concerns about bonding and attachment.

“We heard at every hearing, in every court report, in every meeting how dysregulated Carter was,” Matuszczak recalled.

“The parents’ growth is commendable and undeniable,” a Parent Child Interactional Evaluation submitted to the court by Washington County DHS says. However, the evaluation goes on to say, "Carter's psychological state, his physical development, and his immediate well-being will be profoundly and traumatically affected by a move and change of caregivers." The evaluation then recommended, "that Carter's current placement be made permanent."

“It was hard not to think sometimes, should I give up? Should I let him be with them?” Johansen could see that Carter was very bonded to his foster parents.

“Most parents in these cases see their infants two times a week if they're lucky. Three times a week if they're lucky, and so that's just not enough time for parents to develop a bond, to develop an attachment.” Jordan argued that there are flaws in evaluations like this.

“We know all of the research shows us that children do better long term when they are placed with their families,” she said. “This is definitely one of the biggest miscarriages of justice I have probably ever seen in my career,” she added.

Skyrocketing costs 'This case is one of the most expensive cases that our office has had.'

As the fight to parent Carter entered a third year, the costs added up.

According to the ORPC, the average Dependency and Neglect Case costs $3,500 to litigate, but when foster parents intervene the average court cost goes up to $7,500.

“And that's because there's more motions, there's more people talking. The hearings last longer and there's more litigation that just takes time and takes money to prepare for and to hire experts and to do all the things we need to do to help parents and families,” Jordan explained.

The cost of 19JV13?

“This case is one of the most expensive cases that our office has had,” said Jordan.

The ORPC which provides the couple’s attorneys have legal fees upwards of $137,000 and Washington County’s court costs are at least $144,000. Other costs associated with this case include a $1,200-a-month payment the foster family received for Carter over the past three years, along with court-mandated therapy costs.

“It’s all taxpayer dollars, all state-funded dollars. When there was a parent who was ready and willing and able to support their child available the whole time,” noted Jordan.

19JV13 continued for over three years, with over 600 court filings in the case.

“We would file a motion to increase visits. They would file a motion to cease visits. We would file a motion to have the court deem Fred and Alicia fit parents. They filed the second motion for termination. It was almost tit for tat,” Matuszczak said.

Indications of irregularities Human Services director resigns

Then, in November 2022, there was an unexpected twist, related to indications of irregularities in how the Washington County DHS handled the case.

Attorneys representing Washington County sent a letter to the involved parties of case 19JV13 informing them of an ”employment investigation” ... ”which may have some relevance to the Thornton custody matter.”

According to the letter, a department employee made statements that demonstrated hostility to the birth parents and a “possible promise” to the foster parents.

Johansen blames the Washington County DHS for the delays in her case.

“They made promises, they made decisions, and they had to see those through," she said. "And they became blind to what really was best for Carter or our family, or even what was right. They had promises to keep.”

That same week Grant Smith, the Director of Human Services for Washington County resigned, and Washington County withdrew from case 19JV13.

“I fully believe that if the Washington County director had not resigned, then this case would have gone to a termination hearing and these parents might have had their rights terminated, which is terrifying,” Jordan said.

9NEWS reached out to Smith, who declined to comment on the circumstances surrounding his resignation.

Carter returned to his parent's care 'We're getting to be a family'

Instead of moving forward with a trial to potentially terminate Johansen and Thornton’s parental rights, on Feb. 23, 2023, the court ordered the Termination of Jurisdiction. That meant that three years, six months, and seventeen days after Carter’s birth, he was officially returned to his parent's care.

“Carter is doing so well and he's so happy. And we're getting to do things as things are warming up outside. We're getting to be a family,” said Johansen.

“While I'm really happy that Carter is back home, this family has experienced a loss that none of us can make whole,” Jordan said. “But they should have never been put in this situation. They did what we asked parents to do in these cases, and their son should have come home much earlier.”

“They should have had their kid back two and a half years ago. People need to know how this case was handled so that it doesn't happen to anyone else.” Matuszczak said. “The system needs to change. There needs to be more accountability on who makes decisions about other people's families.”

The Washington County investigation remains sealed by the court, so it is unknown if there are other child welfare cases affected. Washington County DHS told 9NEWS they could not comment about child welfare or personnel issues.

The Office of the Colorado Child Protection Ombudsman filed a motion with the courts to obtain an unsealed copy of the investigation. 9NEWS has not seen that unsealed report. The Ombudsman Office told 9NEWS there is an open case concerning Washington County Human Services. Their review of that case is currently ongoing.

A 2023 bill has passed the Colorado legislature that would increase the time when foster parents can intervene in a case from three months to twelve months. HB23-1024 has been sent to the governor but has not yet been signed into law.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Investigations & Crime