DENVER — As the Colorado’s largest and most prominent medical provider insisted it was “not hiding anything,” an exhaustive investigation discovered UCHealth, for years, used what amounted to a loophole in the state’s court system to keep private its aggressive bill collection practices.

The investigation, led by 9NEWS and the Colorado Sun, prompted the state legislature to quickly close the loophole that had allowed UCHealth to sue thousands of patients for years under another business’ name. UCHealth is short for University of Colorado Health.

Legislators called the project’s findings “shocking” as they quickly passed HB-1380 which will, starting this fall, force hospital systems to sue patients under their own names on debts the systems still own.

RELATED: UCHealth sues thousands of patients every year. But you won’t find its name on the lawsuits.

Among the key findings uncovered by the investigation:

- In early 2020 and unbeknownst to legislators and the public at large, UCHealth quietly ended its yearslong practice of suing patients under its own name.

- The decision allowed UCHealth to continue to sue patients – roughly eight per day for years – with virtually no way to track its legal efforts.

- As UCHealth allowed two of its third-party debt collectors to use their names as plaintiffs, it turned a once-transparent process into a confusing and opaque mess for many of its patients.

- After the investigation confronted UCHealth leadership on the issue, the hospital system revealed that it had sued more than 15,000 patients in five years, making it one of the most aggressive litigants in the state of Colorado.

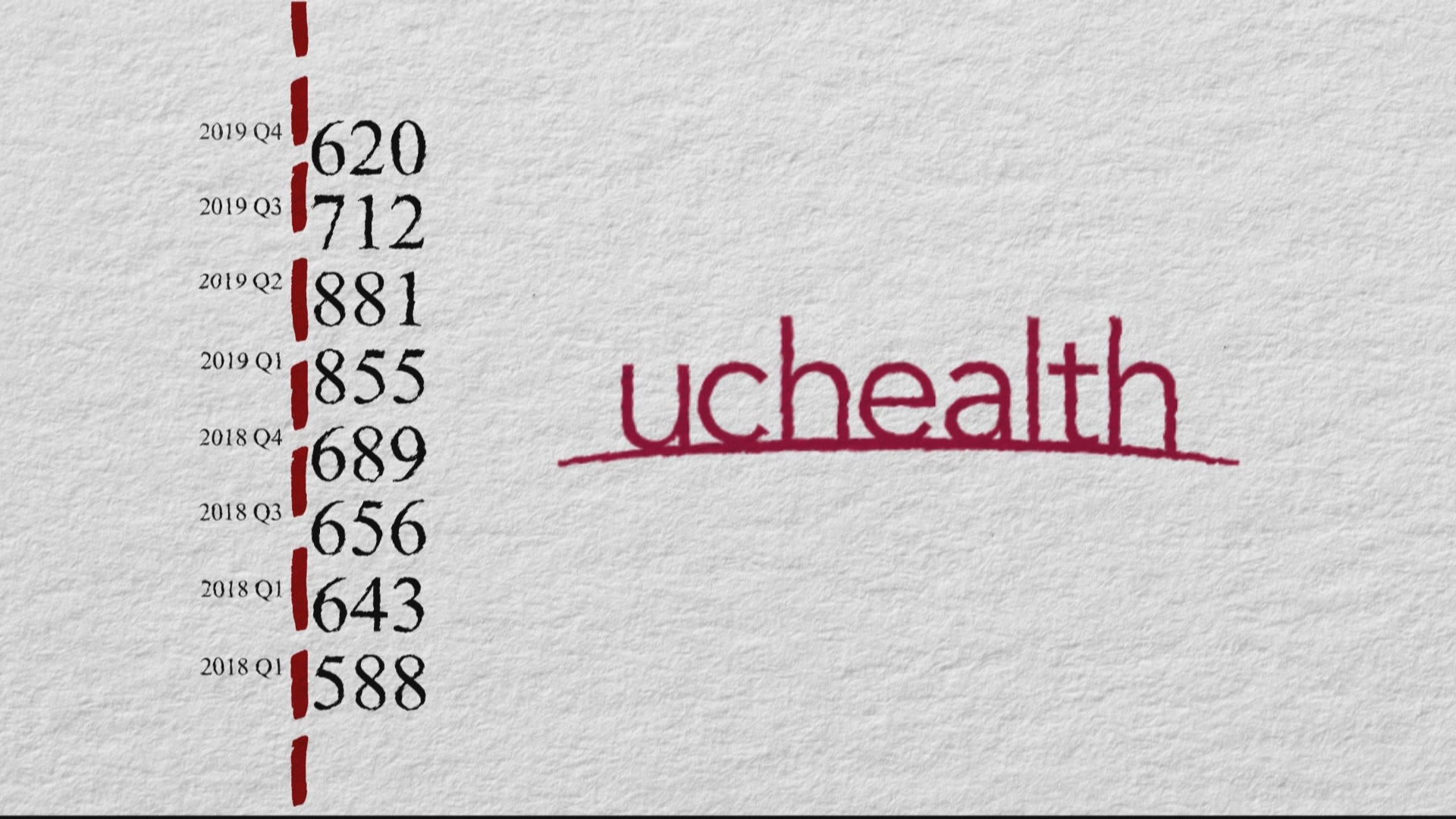

This investigation technically began in late 2019 and early 2020 when investigative reporter Chris Vanderveen, acting on a tip, began searching state court records looking to quantify the number of lawsuits filed by the state’s largest medical systems. At the time, he discovered UCHealth appeared to file more lawsuits than any other system.

As Vanderveen was preparing to move forward with the investigation, the pandemic hit. Like many reporters across the United States, he turned his attention elsewhere.

By late 2020, he returned to his analysis of state court records only to discover something he found perplexing.

It appeared, at least on the surface, UCHealth had largely ended its litigation practices. A few hundred lawsuits filed every month in 2019 had turned into one or two, at most, in 2020.

Only later – following months of records requests, phone conversations and data analysis – did Vanderveen learn the secret.

UCHealth never stopped suing patients in early 2020; it just stopped doing it in a publicly traceable way.

“I really do think we owe you a little bit of thanks – maybe a lot of thanks and gratitude – for sure, because it pointed us in the right direction,” said state Sen. Sonya Jaquez Lewis, one of the main sponsors of HB-1380.

The legislation, passed in the final days of the 2024 legislative session – will compel hospital systems like UCHealth to list themselves as plaintiffs.

“Now we will be able to know how many times a Colorado hospital takes a Coloradan to court,” said Sen. Jaquez Lewis. “I was shocked by your story,” she told Vanderveen.

While UCHealth’s chief legal officer told Vanderveen during an on-camera interview, “Our job is to stay out of the courts,” the 9NEWS investigation found no other medical system in Colorado worked as hard as UCHealth to send its patients to court.

And that left thousands of its patients vulnerable to litigation they were ill equipped or ill prepared to experience. The investigation found numerous examples of that.

Lorena Sanchez, for example, faced a $24,000 lawsuit – filled by a company she did not know – years after an hour-and-a-half visit to a UCHealth emergency room.

“When you go through that and you see that dollar amount for an hour-and-a-half, it doesn’t make sense,” she said. When a debt servicer showed up at her door with the lawsuit filed Credit Service Company, and not UCHealth, she said, “I got sick. My blood pressure went up because I got scared.”

It was a story the project heard over and over again.

Who was suing me? Why do I owe this?

“It’s very confusing,” said Michelle Weeder as she attempted to navigate the Adams County, Colorado, courthouse. “This is pure bullsh--!’

When a summons arrived at her front door signed by Credit Service Company, Gabrielle St. James thought it was a scam. “I had no idea who they were,” she said.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS: Investigations & Crime