COLORADO, USA — Every year in Colorado, roughly half the children who die of abuse or neglect are ignored by the system that’s supposed to protect them – cases where there’s no investigation aimed at figuring out what went wrong and learning lessons that might prevent future deaths.

Stephanie Villafuerte, Colorado’s child protection ombudsman, wants to change that.

“What we’re really saying is we’re trying to actually reduce the number of child abuse deaths in our state, but we're only going to look at 50 percent of the problem,” Villafuerte said. “I don’t know how you look at 50 percent of the evidence and solve anything.”

Villafuerte’s job as the independent monitor of the child welfare system was created in the wake of a horrific abuse case, the 2007 killing of a 7-year-old boy named Chandler Grafner. He was locked in a closet and starved by his guardians, he weighed 31 pounds when he died.

“We’re reactive, right?” Villafuerte said. “We react when a child dies and then everybody scrambles, and quite frankly we work very hard to find a villain and a victim. I have watched this cycle for the last two decades. It's happened under the last three governors that we have had in our state.

“And the reality is, I wish we could really reduce these things to villains and victims, but it isn’t that simple,” she said.

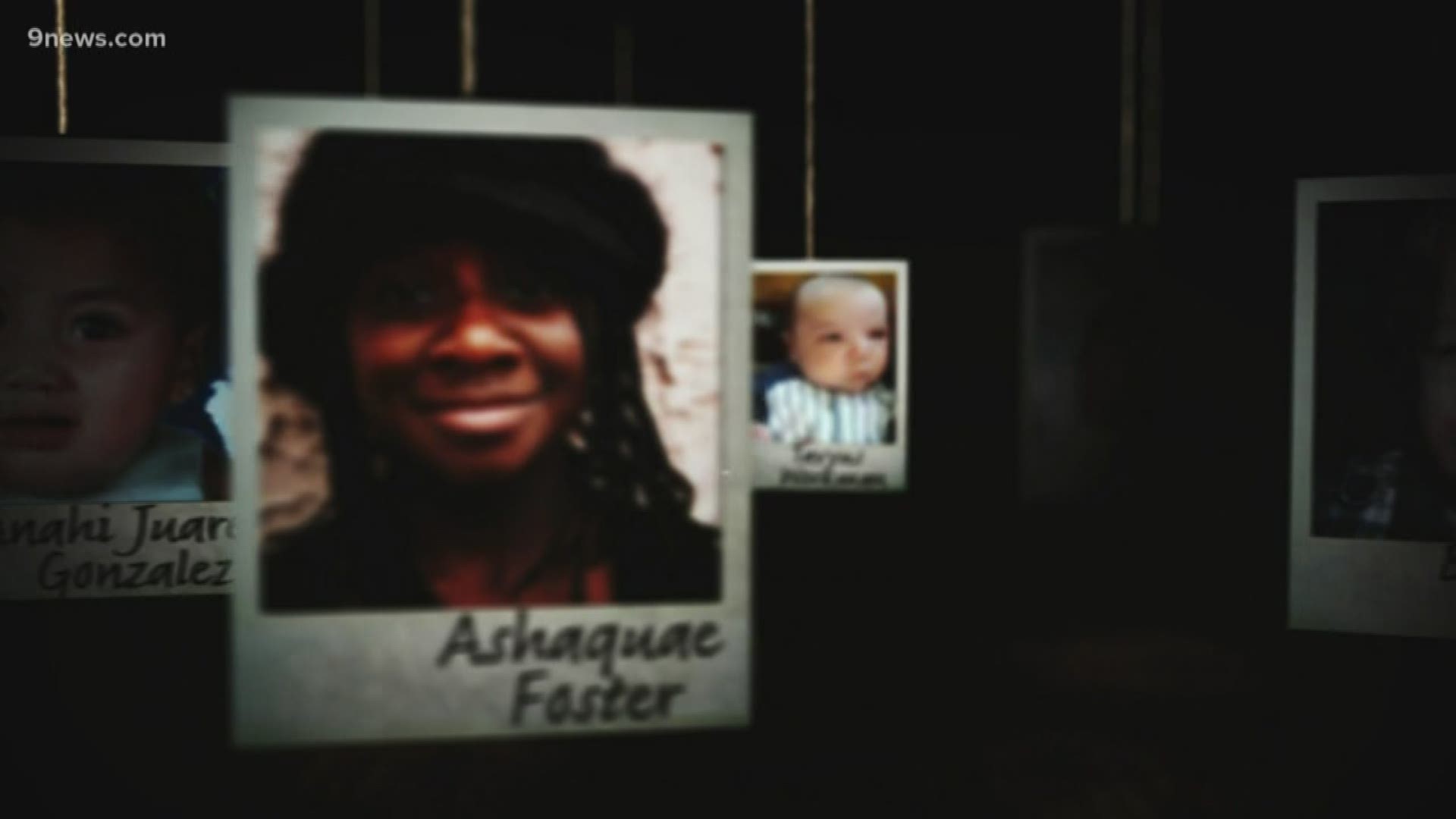

That cycle repeated itself in 2012 after a 9Wants to Know/Denver Post investigation found that dozens of children died who were already known to child protection services workers.

The reforms that followed included the creation of a hotline and a requirement that deaths be reported.

“I have seen routinely is these hurried up commissions, a series of recommendations which, by the way, were positive,” Villafuerte said. “And then once those recommendations get implemented, everybody leaves until we start over again.”

Even with reforms in recent years, the number of deaths continued to climb – from 23 in 2015 to 35 the next two years and 36 in 2018. Numbers for 2019 have not been finalized, but it appears that there were fewer abuse and neglect deaths in the state.

Even so, this week Villafuerte called on Colorado to do more.

Current law, for instance, calls for an investigation of the abuse or neglect death of a child only if he or she – or a family member – had contact with child protection workers in the previous three years. That’s why about half of the deaths aren’t investigated with an eye toward learning from them and preventing the same thing from happening again.

And there’s also another problem.

“There is no entity responsible today for taking those recommendations, implementing them, or monitoring them,” Villafuerte said.

She pointed to a situation a few years ago where a child’s death led to the recommendation that doctors receive more training in identifying the signs of abuse or neglect – but no real ability to make sure it was followed.

That’s why this week she called for both things to change – for an investigation of every abuse and neglect death of a child and a better effort to share recommendations with doctors, ministers, police officers, social services workers and other who have contact with children.

Villafuerte said she and her staff intend to spend the next couple of months looking at ideas and expect to issue a plan to make changes later this spring.

Continuing to ignore roughly half the deaths and failing to follow up on recommendations has “got to change,” she said.

“I think that you can make progress when you do that,” she said.

Editor’s note: This story was produced in partnership with The Colorado Sun.

Contact 9NEWS reporter Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story: kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS | Investigations from 9Wants to Know