DENVER — Forty-three Catholic priests have been credibly accused of sexually abusing at least 166 children in Colorado since 1950, according to a ground-breaking report made public Wednesday morning.

One priest, Father Harold Robert White, had 63 substantiated allegations lodged against him. In the report, the Colorado Attorney General’s Office referred to White as "the most prolific known clergy child sex abuser in Colorado history.”

"His sexual abuse of children began before he was ordained in 1960, and it continued for at least 21 years in at least six parishes from Denver to Colorado Springs to Sterling to Loveland to Minturn to Aspen," the report reads.

" … This one priest’s career and the Denver Archdiocese’s management of it present a microcosm of virtually all the failures we found elsewhere in our review of the Colorado Dioceses’ child sex abuse history."

White died in 2006 at age 73. Though the first accusations against him were made in 1960, he wasn't permanently removed from the ministry until 1993.

“The culture where people wanted to protect priests enabled this to go on, enabled priests to engage in multiple acts of abuse," Weiser said. "When you see that the same priest could commit so many acts of abuse, you’re just left pained and breathless that people didn't act differently.”

The report found that from 1950 to present:

- At least 127 children were victimized by 22 priests in the Archdiocese of Denver.

- At least three children were victimized by two Roman Catholic priests in the Diocese of Colorado Springs.

- At least 36 children were victimized by 19 Roman Catholic priests in the Diocese of Pueblo.

- One allegation is still potentially viable for prosecution within the relevant statute of limitations. It had already been reported to authorities.

According to the report, just five of the Colorado priests had abused at least 102 of the 166 known victims. Two-thirds of those victims were abused in the 1960s and 1970s.

On average, it took nearly 20 years for the church to restrict a priest’s authority after receiving an allegation of sexual abuse, the report found.

The report outlined a culture of secrecy slow to out one of their own. Investigators found evidence as late as the 1980s where whistleblowers were punished. Since 2002, the church failed to report 64% of recorded sex abuse allegations.

“Out of almost 100 opportunities to do so since 1950, the Colorado Dioceses voluntarily reported clergy child sex abuse to law enforcement fewer than 10 times. It is impossible to believe that church personnel did not know even in 1950 that sexually abusing a person is a serious crime.”

Jeb Barrett is a sexual abuse survivor and local leader of SNAP, the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests. Barrett said he kept the pain and shame of his abuse secret until he was 63. He gave us his perspective on how abuse affects victims:

DATABASE:

You can search for information about the priests named in the report below. You can search by name, diocese and parish. To see a full list of the priests, leave the search field blank and hit "enter."

The author of the report, Former U.S. Attorney Robert Troyer, talked to us about it:

Denver Archdiocese

The following are the findings from the report released Wednesday:

- At least 127 children were victimized by 22 priests in the Archdiocese of Denver.

- 2002 to present, the Denver Archdiocese failed to report 25 of 39 recorded allegations of clergy child sex abuse that Colorado law required it to report to law enforcement.

- In most of the cases, the victim was an adult when the abuse was reported, and the priest was already out of the ministry.

- The church might have believed it was not required to report the abuse because the victim was an adult when it was reported and/or the accused priest was now deceased.

- In some cases abuse was not reported because the victim wished to remain anonymous, however the report notes, that does not excuse a "mandatory reporter" from reporting.

- Denver Archdiocese has complied with the mandatory reporting law since 2009.

In an emailed statement, the Denver Archdiocese said: "Despicable things happened in our parishes, and at the time there were incredible failures to properly address them. The Archdiocese of Denver in 2019 is much different than it was decades ago. We have taken huge steps to address this issue, and the report documents the dramatic decrease in known substantiated allegations. We make no claim that the problem is forever solved, but rather are reminded today that we must remain vigilant to ensure our parishes and schools remain safe."

Archbishop Samuel J. Aquila addressed the Catholic community directly in the following video:

REPORT:

Diocese of Colorado Springs

The following are the findings from the report released Wednesday:

- At least three children were victimized by two Roman Catholic priests in the Diocese of Colorado Springs.

- There were no incidents where the Diocese failed to report.

- One Colorado Springs Diocese priest found to be a substantiated child sex abuser.

- When that priest committed the alleged abuse between 1980 and 1986, Colorado law did not mandate clergy reporting of child abuse.

- The alleged abuse was not reported "voluntarily" to law enforcement.

- Second priest listed in the report only as "Father E".

Diocese of Pueblo

The following are the findings from the report released Wednesday:

- The Pueblo Diocese’s files do not indicate its personnel received any allegations of clergy child sex abuse between 1969 and 1975.

- At least 13 clergy child sex abuse allegations were reported to personnel between 2002 and the present that Colorado law required it to report to law enforcement.

- Four were reported immediately as required by law.

- The other nine were not immediately reported to law enforcement.

- The last time the Pueblo Diocese failed to follow Colorado’s mandatory reporting law was almost 10 years ago.

- Two reports of prior sex abuse were reported to law enforcement in 2019 shortly after they were received.

- Three clergy child sex abuse allegations made between 2002 and 2010 that the Pueblo Diocese did not report to law enforcement even though the accused priests were alive at the time and the Pueblo Diocese had reason to believe they were in positions of trust with children.

- Currently, the Pueblo Diocese has protocols in place to obey Colorado’s mandatory reporting law and has voluntarily reported the only three allegations it received in the last 5 years.

Father Michael Desciose is accused of abusing a 14-year-old boy in 1986 or 1987 while he served in the St. Joseph's Parish in Grand Junction. He now lives in Denver, and 9NEWS spoke with him on Wednesday afternoon and denied the allegations.

"I just want to say that what I was accused of I did not do," DeSciose said. "I think it was trumped up. He was prompted to say what he did. It is not true. I’ve maintained that all through this examination."

The alleged abuse was first reported in 2018, according to the report, which also notes that he "repeatedly denied the allegation."

DeSciose said he is unsure why the report names him.

"I am disturbed by that. Again, it is not true," he said. "I retired as hospital chaplain... You’re guilty until proven innocent."

DeSciose retired in 2012. The Pueblo Diocese suspended his faculties in 2018 pending the outcome of the preliminary investigation. DeSciose’s faculties were previously suspended in 2016 when he admitted to multiple sex acts with adult men, according to the report.

Documentation in his file indicates his faculties were restored in 2017 after he attended counseling in Denver.

The Attorney General’s office made a critical error when it released this report, failing to redact the surname of one victim, Jason Faris, who spoke about the mistake with 9NEWS.

“Truth be told it was probably a clerical error on someone’s part. But a pretty egregious clerical error,” he said. “Protecting the privacy of victims of sexual abuse is of paramount importance. It’s one of the things that actually encourages victims of sexual abuse to come forward and tell their story.”

Faris said was sexually assaulted by former priest Tim Evans when he was a teenager. He met regularly with Evans, his spiritual advisor. According to the report, in 1996, Evans instructed the then 17-year-old to take off everything but his underwear. Evans proceeded to caress him head to toe, avoiding the genitals, the report says. Faris and several other victims ultimately testified against Evans. He’s now in prison.

Faris, who remains a practicing Catholic, now works with victims of clergy sexual abuse part-time for the Capuchin Franciscans in Denver. He hopes the mistake by the Attorney General’s office doesn’t deter victims from coming forward.

“Their story is so important. Not only for the sake of justice, but also for their own healing. By holding back their story, that just emboldens the darkness that they live in and are surrounded by. And by telling their story, that’s the light that pierces that darkness,” he said.

Below are some common questions and answers about the report:

Why was this report done?

Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser reached an agreement with the leaders of the Archdiocese of Denver, the Diocese of Colorado Springs and the Diocese of Pueblo for an accounting of sexual misconduct involving minors by priests. The work on this agreement was begun by former Attorney General Cynthia Coffman.

What exactly did the review look at?

It looked at reports of clergy abuse by diocesan priests and the response of the church, including its policies and procedures aimed at preventing future sexual misconduct with children.

Who conducted the review?

Former U.S. Attorney Robert Troyer.

Who is listed in the report?

Priests against whom a “substantiated allegation” exists.

What constitutes a “substantiated allegation”?

One where Troyer concluded the evidence shows that the abuse more likely than not occurred.

What period of time does the report cover?

Jan. 1, 1950, to the present.

Was this a criminal investigation?

No. However, if crimes were uncovered that could be prosecuted, they were to be reviewed and forwarded to the appropriate law enforcement agencies for further investigation.

What information was used to compile the report?

It was based largely on internal church records. However, Troyer had the power to conduct follow-up interviews and consider new reports that hadn’t previously been made to the church.

Did the review look at every Catholic priest who has been in Colorado since 1950?

No. It considered only priests in the three dioceses in Colorado. It did not include religious order priests.

Is there compensation available for victims?

Yes. A separate, companion agreement established an independent process to pay reparations to victims of clergy sex abuse. Kenneth Feinberg and Camille Biros are administering that process and have the sole discretion to decide how much money an abuse survivor should be paid. The three Colorado dioceses have agree to abide by their determinations.

How much money could a sexual abuse victim expect?

It’s difficult to say. However, Feinberg said in other states where he has made similar determinations, payments ranged from as little as $10,000 to as much as $500,000.

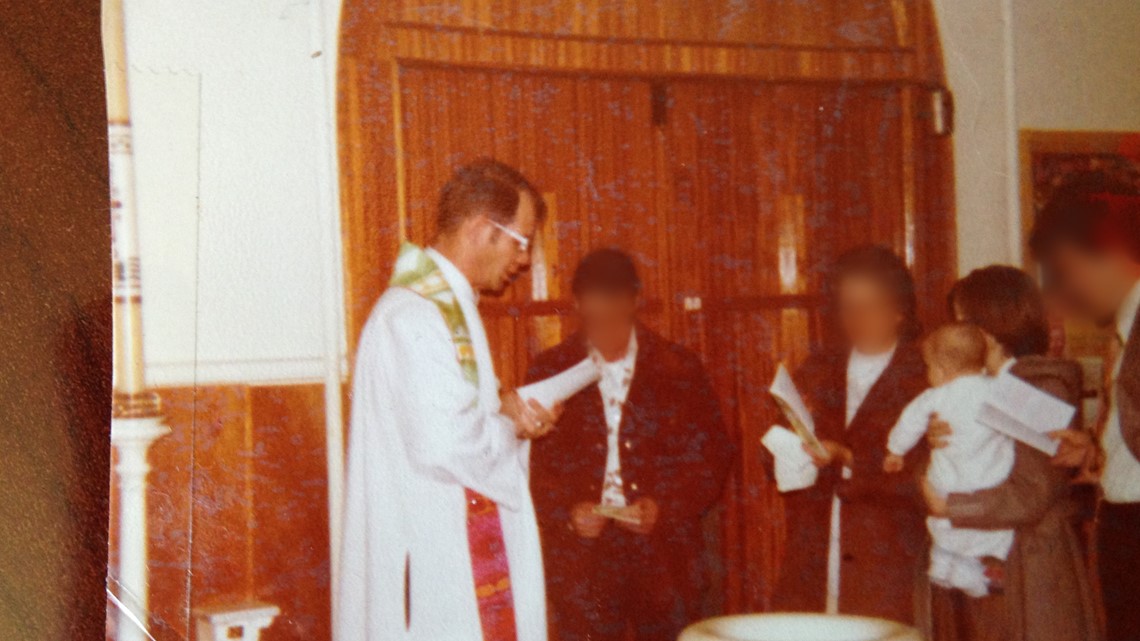

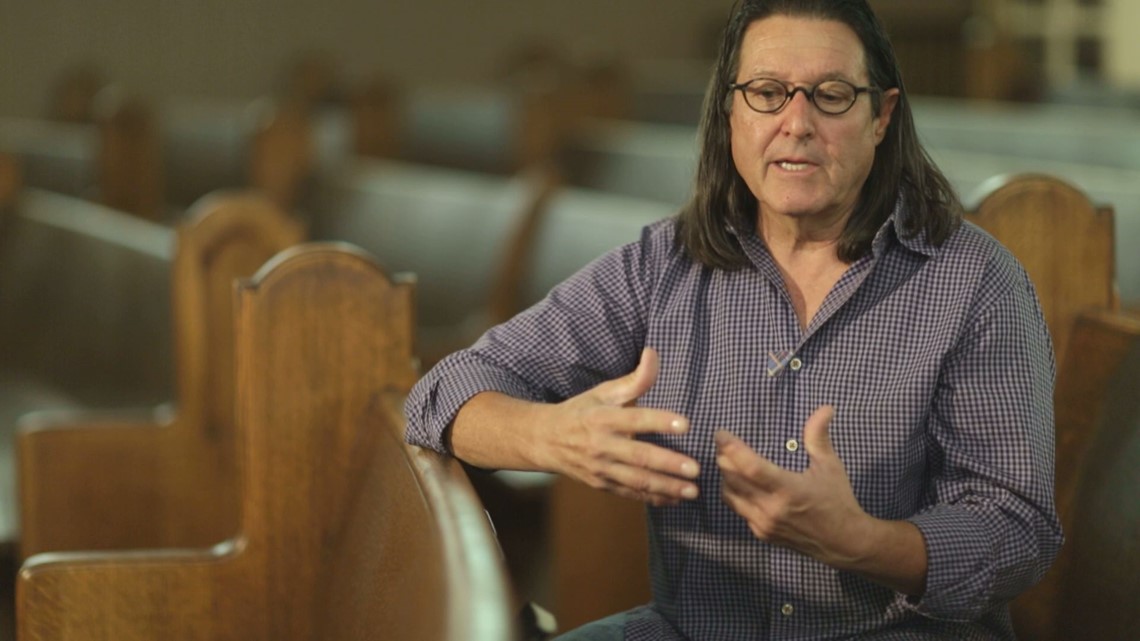

Earlier this year, 9Wants to Know told the story of Michael Smilanic, who filed a formal complaint with the Catholic church in 2017 and recounted in May how he was abused by Father Neil Hewitt in 1967. The report released Wednesday says Hewitt abused a "minimum of eight boys" and began his abuse between 1962 and 1965 when he was assigned to St. Anthony Parish in Sterling.

Smilanic never told anyone about the abuse until after he saw the 2015 movie “Spotlight,” which delved into the Boston Globe’s investigation of child sexual abuse by Catholic priests in Massachusetts.

“As a kid, I was really embarrassed and very confused – and then kind of felt like some of it was maybe my fault,” he said.

After seeing the movie, he finally told his wife what happened all those years ago.

“She kind of didn't know what to say, but she was very supportive and very saddened by it,” Smilanic said.

The priest he named — Hewitt — was ordained in 1962, but left the ministry in 1980, and then got married. Before Smilanic came forward in 2015, the report says the Denver Archdiocese received a report of sexual abuse against Hewitt in 1992-- almost 13 years after the alleged abuse. They received a second report of prior abuse by Hewitt in 2002, according to the report. It wasn't until 2008 that the Diocese reported the suspected to abuse to Leadville police, the report says.

“During his ministry, there was never any reports of misconduct with a child, and no reports of sexual abuse of a minor while he was in ministry,” Mark Haas, spokesman for the archdiocese, told 9Wants to Know in May.

However, there have been at least two complaints filed against Hewitt since he left the priesthood. Both reports — one of which was Smilanic's — alleged that he sexually abused teenage boys in the 1960s while he was an active priest.

Investigators interviewed Hewitt in August 2019 and, according to the report, he admitted to "seven of eight incidents of child sex abuse" that were made against him. Four of the incidents were first uncovered through the investigation.

Smilanic tracked Hewitt down and said that Hewitt admitted to wrongdoing.

“He didn't hem and haw, he didn’t – there wasn’t a long silence or anything. He admitted it right away, and he said that he was sorry, and said, 'I didn't think it was wrong; I don't know why it started,'" Smilanic told 9NEWS.

Hewitt, now in 80s, declined to sit for a formal interview with 9NEWS, but spoke with a reporter on the porch of his Arizona home.

“I did do things that were wrong,” Hewitt said. “I realize that. About all I could do is what I did with Michael, you know, and just say, 'I’m really sorry.'"

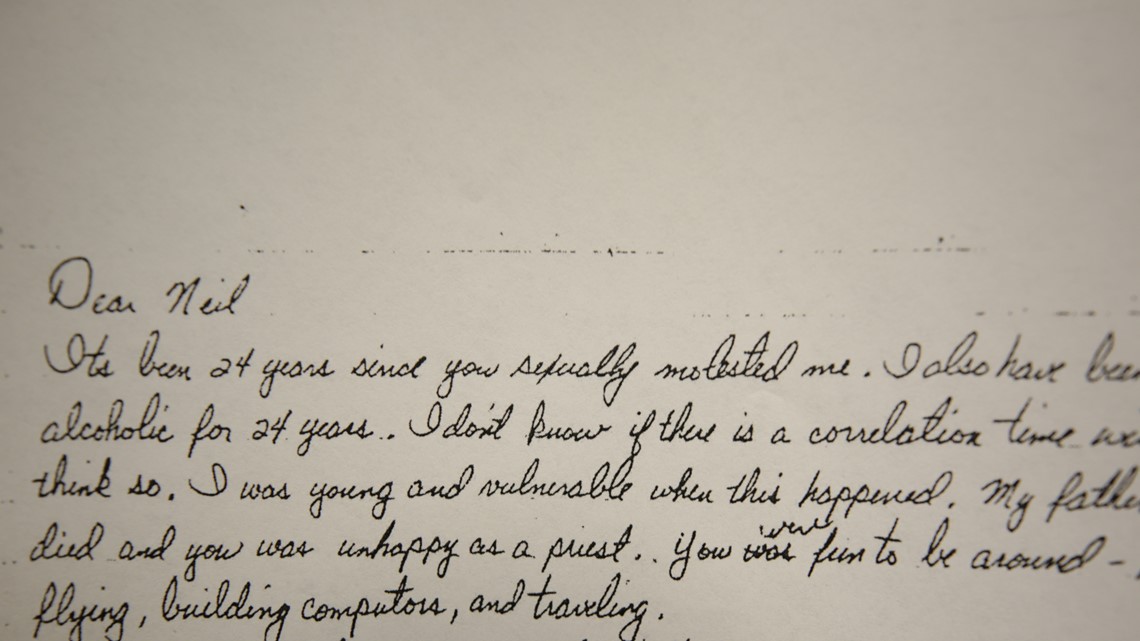

The second complaint against Hewitt was filed by Donna Ballentine, whose cousin took his own life in 1991. Years after his death, Ballentine discovered a letter he'd written in which he accused Hewitt of molesting him.

RELATED: Letter alleging Colorado Catholic priest's abuse found a decade after the author took his own life

Wednesday's report acknowledges that "one of Hewitt's victims was driven to suicide as an adult."

To be eligible for compensation, victims have until Nov. 30 to contact the program to start the process of filing a claim.

Independent claims administrators Kenneth R. Feinberg and Camille S. Biros are administering the compensation program and have the sole authority to decide how much money a survivor should be paid. The three dioceses have agreed to abide by the decisions Feinberg and Biros make.

Packets have already been already sent to 65 people who had previously reported being abused by diocesan priests to church officials.

All claims must be filed by Jan. 31, 2020 and can only be made concerning clergy who worked for Colorado dioceses, not members of independent religious orders. The names of those who make claims will not be made public.

“The program is guaranteed to be confidential,” Feinberg said last month.

He said Colorado's program is very similar to those he is administrating for Catholic dioceses in four other states— California, New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. Payments in other state have ranged from $10,000 to $500,000, he said.

Colorado announced its review of clergy abuse following a Pennsylvania report from a grand jury in late 2018 that showed more than 300 priests there abused 1,000 children over the course of 70 years.

Weiser said unlike Pennsylvania, he does not have the power to bring the case to a grand jury, so the review was not a criminal investigation, but could potentially lead to criminal charges.

“If matters come forward that are appropriate for a referral to a district attorney and criminal investigations, that is going to be a part of this process,” he told 9Wants to Know.

According to the report, just one allegation was found that could potentially still be prosecuted under the statute of limitations. It had already been reported to the appropriate law enforcement.

RELATED: Most priests can't be prosecuted, even if they are named in the sex abuse report. Here's why

If any individual knows or suspects current child abuse by anyone acting on behalf of the Archdiocese of Denver or on behalf of the Catholic parishes and schools within the archdiocese, they're urged to immediately report it to law enforcement or to the Colorado Child Abuse Reporting Hotline at 844-CO-4-KIDS and also to notify the Archdiocese of Denver Office of Child and Youth Protection at 720-239-2832.

Contact 9NEWS reporter Kevin Vaughan with tips about this or any story: kevin.vaughan@9news.com or 303-871-1862.

SUGGESTED VIDEOS | Investigations from 9Wants to Know